Geert Wilders’ surprise victory in the 2023 Dutch general election has rightly grabbed headlines, write Nick Martin and André Krouwel. But the election was remarkable for several other reasons, not least the realignment of the party system brought about by unprecedented levels of electoral volatility.

At every Dutch election since 2003, voters have expressed their discontent with mainstream parties by turning to radical actors. In 2006 it was the radical left Socialist Party (SP) with 16.6% of the vote that was the electoral vehicle of discontent, and between 2010 and 2021 the mantle of discontent fell to Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV).

But never until this year’s election had a party from the radical fringe topped the vote or obtained more than 20% support. When the 23.7% achieved by the PVV is added to the vote for the centrist anti-establishment and new entrant New Social Contract (NSC) and the Farmer–Citizen Movement (BBB), a striking 42.3% of Dutch voters lent their support to parties explicitly critical of the country’s political establishment.

This watershed moment in Dutch politics has rightly grabbed international headlines and caused a wave of shock and anxiety among western Europe’s political establishment. But the 2023 Dutch general election was also remarkable for three other reasons.

The implosion of the governing coalition

First, there was the strategic miscalculations and electoral implosion of the centrist and right-wing parties that made up the country’s outgoing coalition. The four-party governing coalition fell apart in July this year over the plans of Prime Minister Mark Rutte to reduce migration levels by establishing stricter rules on family reunification for asylum seekers.

Having fallen out over migration, the parties of the outgoing coalition made the mistake of fighting the election on the issue and the ground most favourable to Wilders and the PVV. To compound this error, the new leader of the prime ministerial party, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), indicated that the party would be open to forming a coalition with Wilders in it. This removed one of the principal factors constraining voters sympathetic to Wilders from voting for his populist party. Support for the outgoing collation duly melted away, falling from 49.2% in 2021 to just 27.9% this year.

Failure for the left

Second, there was the failure of the electoral alliance of two mainstream left parties to mobilise progressive opposition to the radical right. In July this year, the members of the Netherlands’ two mainstream parties of the left, the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA) and the Green-Left (Groen Links), voted overwhelmingly to run on a joint programme and with a joint candidate list at the election. Choosing the veteran social democrat and European Commissioner Frans Timmermans as its leader, the alliance hoped to rally the Dutch left around a vision of a “social and green” Netherlands.

While the alliance did gain eight seats and recovered partially from the two parties’ worst ever combined vote in 2021, drawing a lot of support in particular from the liberal D66, the alliance must be considered a failure. It failed to achieve the highest single list vote share at the election and failed to mobilise the left overall to form a strong bloc in parliament. Overall, the Dutch left fell to its worst electoral result in more than 40 years, with the parties of the left winning the support of barely 26% of Dutch voters.

Unprecedented volatility

Finally, there were unprecedented levels of electoral volatility and switching between parties by Dutch voters, right up to the vote itself. Measured at the aggregate level, the 2023 general election was the most volatile in Dutch history. The movement of individual voters between different parties was unprecedented. According to the NOS exit poll, none of the outgoing coalition parties retained more than half of their 2021 voters.

D66, the second largest party in 2021, retained just 27% of their 2021 voters, with 31% of these voters opting instead for the Groen Links/PvdA alliance. The PVV in contrast retained 79% of its 2021 voters and drew in support from the VVD and two smaller radical right parties, the FvD and JA21. And the new kids on the block, the NSC and the BBB, gathered support across the political spectrum, but particularly from voters of the outgoing coalition who constituted 58% of the NSC vote and 35% of the BBB vote.

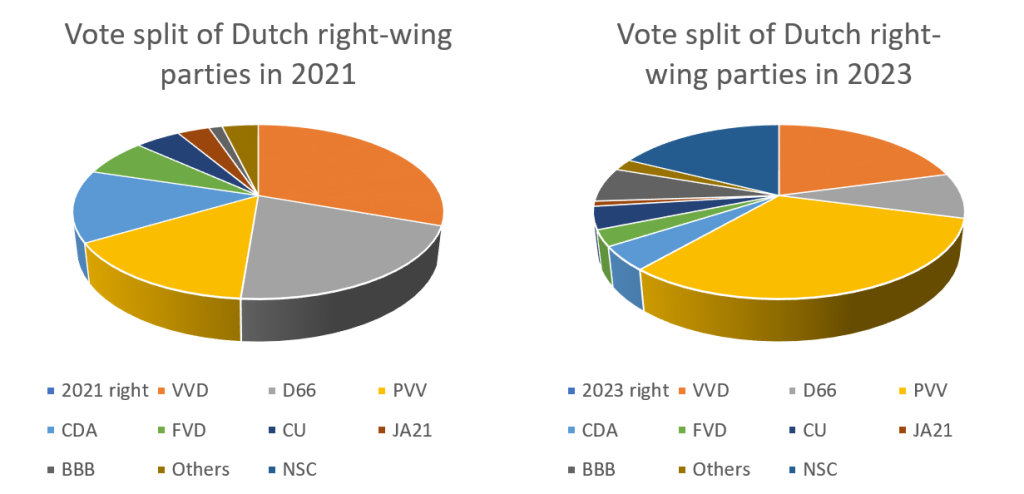

One consequence of this movement was a fundamental realignment of the centre and right parties in the Dutch political system. Figure 1 illustrates just how dramatic this realignment on the right has been. The dominance in 2021 of the Dutch right by the VVD and D66 has disappeared to be replaced by the PVV and NSC, who together now account for virtually 50% of the vote for right-wing parties in the Netherlands.

Figure 1: Vote split between Dutch right-wing parties in 2021 and 2023

Note: Compiled by the authors.

With the populist, anti-establishment bloc now being almost as large as the traditional centre-right parties – if we generously add NSC to the moderate right because of its deep roots in CDA circles – Dutch politics has transformed into a system where three political blocs compete. This three-way division between the populist, authoritarian, nativist right bloc, the Left-plus-Green bloc and the liberal centre/centre-right bloc is similar to the French situation in 2022. This shift in the balance between party blocs may be a precursor of what is to come in the European elections of 2024.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Jeroen Meuwsen Fotografie/Shutterstock.com