What impact does political indoctrination have on children? Using data from Poland, Anna Nicińska shows that political indoctrination at school reduces educational attainment and labour force participation later in life. These effects seem to operate through a reduction in individual agency.

Political indoctrination at school is often designed to influence trust in government. Previous studies have shown that indoctrination at school can be instrumental to the consolidation of political power, while others show that ideology in school education materials can successfully instil socially-useful beliefs and cultivate good citizenship. However, teaching individuals to uncritically accept beliefs might also exert negative effects on later life.

Research suggests an absence of critical discourse in education can hinder the development of individual agency, which is important for making effective career choices. Other studies point to a link between compulsory religious education in German schools and increased labour market participation and earnings. Research also suggests that Nazi schooling significantly increased anti-Semitism in Germany.

Indoctrination in Polish schools

In a recent study, co-authored with Joan Costa-Font and Jorge García-Hombrados, we examine the impact of a reform in Poland that reduced political indoctrination in schools in the mid-1950s, while leaving the rest of the curriculum unchanged.

Political indoctrination featured heavily in the education system that was implemented in Poland following the end of the Second World War. By 1949, Poland had adopted the Soviet approach to education, instilling Marxist-Leninist values and promoting loyalty to the regime, as well as the idea of “new Soviet men” who were physically fit and strongly attached to the Soviet community.

However, after the death of Joseph Stalin, the Polish government implemented a reform in 1954 that dramatically reduced the amount of indoctrination in the school curriculum. This change affected all subjects, including history, mathematics, music, technical education, physical education and the teaching of the Polish language. School assemblies were no longer dedicated to communist leaders and pupils were no longer required to recite ideological poems or sing communist anthems.

What impact did these changes have on pupils in Polish schools?

We use 2002 Polish census data on labour market participation and human capital attainment for 200,706 individuals to help assess the long-term consequences of the reform. We use a difference-in-differences approach to compare individuals born in the first quarter of the years leading up to the reform and those born in the last quarter of the previous year.

Those born in the first quarter of a year, despite being just a few weeks or months younger than those born in the last quarter of the previous year, were exposed to an additional year of education under the new education system. This allows us to measure the impact of the reform.

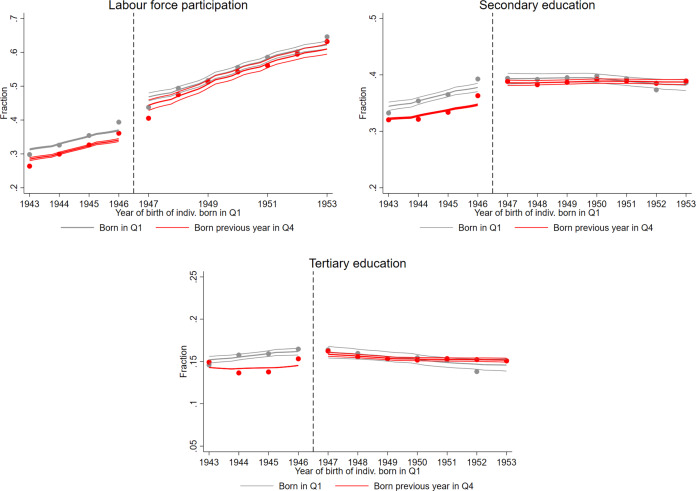

Figure 1: Impact of the 1954 education reform on human capital and labour force participation

Note: The year indicated in the X-axis refers to the year of birth for those born in the first quarter and to the year of birth -1 for those born in the last quarter of the previous calendar year. Lines represent fits from a local polynomial with a bandwidth of 1 and 95% confidence intervals. Data is from the 2002 Polish census.

As shown in Figure 1, our research suggests that for each additional year a child spent in education after the reform, their probability of finishing secondary and tertiary education increased by 1.15 and 1.42 percentage points respectively. Their labour force participation 50 years later also increased by 1.69 percentage points. These findings suggest a negative impact from political indoctrination prior to the 1954 reform.

The importance of values

Similar detrimental effects from communist education have also been found in research on education in East Germany prior to reunification. But what explains this effect?

Our results suggest that values promoted at school might be crucial for outcomes in later life. An individual’s sense of agency and independence from authorities seem to have a particularly important impact. The influence of a political regime on the curriculum taught in schools and autocratic elements in a schooling system appear to limit the long-term benefits of education.

We use data from three waves of a major survey of Polish citizens – the Diagnoza Społeczna survey – to examine this effect. This survey includes rich information on values and attitudes. We find a significant causal impact from the 1954 education reform. Individuals with less exposure to political indoctrination at school tend to place the responsibility for their overall life circumstances on themselves to a larger degree and on the country’s authorities to a smaller degree than those with greater exposure.

This sense of greater agency and independence from authorities might stem from a greater focus at school on scholarly activities and the acquisition of skills, rather than on obedience to authorities and loyalty to the communist regime. Agency and independence appear to be associated with the ability to shape one’s destiny, which aligns with the increased labour market participation and educational attainment we find in our analysis. Interestingly, we found little impact on the likelihood of these individuals holding left-wing political views.

Whether political indoctrination in non-communist autocratic regimes would yield similar negative effects is an open question. However, the fact the negative effects of communist indoctrination seem to be tied to the suppression of individual agency suggests that these results might be applicable in autocratic regimes across the political spectrum.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in the European Economic Review (co-authored with Joan Costa-Font and Jorge García-Hombrados)

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Aquir / Shutterstock.com