Many Ukrainian citizens have sought protection in Norway since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Presenting findings from a new survey, Aadne Aasland writes that while most Ukrainian refugees report having a positive experience in Norway, the Norwegian authorities are increasingly pursuing a tougher approach.

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many Ukrainian citizens sought protection in other European countries. Initially, Norway was not among the countries with the highest per-capita number of temporary protection applicants among EU or EFTA countries. However, the current scenario is markedly different. In the third quarter of 2023, Norway received nearly as many displaced individuals from Ukraine as the other Nordic countries combined. Additionally, the growth rate of new applicants was the highest among all EU and EFTA states.

More than 70,000 displaced individuals from Ukraine have now sought collective protection in Norway, according to the Norwegian Directorate of Migration. This significant influx, in comparison to neighbouring countries, is causing concern among Norwegian policymakers. Municipalities, who are responsible for housing and other welfare services, report saturation points being reached. The challenge of finding housing has increased and there is a fear that a continuous inflow might impact other services such as healthcare and education.

In early December, the government implemented restrictions on the rights that displaced individuals from Ukraine had previously enjoyed. Norway became the first country in Europe to introduce limitations on free travel between Ukraine and Norway for those with temporary protection. This means a Ukrainian mother in Norway may no longer be allowed to meet her husband and her children may be unable to see their father, who might be fighting on the frontline and not allowed to leave the country. Other changes included limitations on child benefits during the first year and a lowering of accommodation standards for new arrivals. On 29 January, the government announced further restrictions for displaced individuals from Ukraine.

Why have so many Ukrainians chosen to come to Norway?

A new and comprehensive research report on the reception and integration of displaced Ukrainians in Norway sheds light on this. In a survey conducted with more than 1,600 displaced Ukrainian respondents in October-November 2023, participants were asked to assess their general satisfaction with their reception in Norway.

On a scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied), the mean response was close to the maximum: 4.7. Subsequent cohorts of displaced individuals turned out to be even more satisfied than those who arrived earlier. Both national and local actors that Ukrainians are likely to encounter during their initial phase in the country received scores above 4, often closer to 5. Ukrainians also feel welcomed by the Norwegian people (4.6).

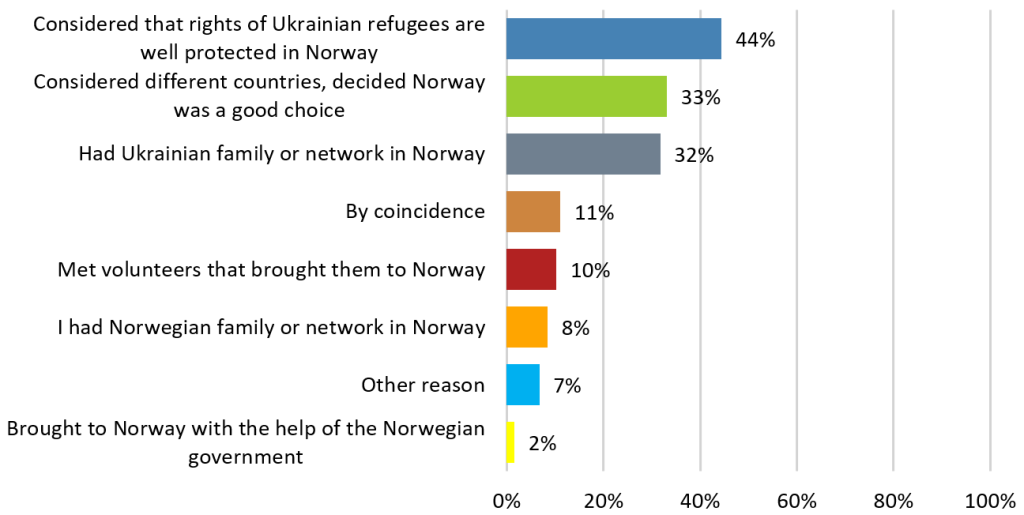

When asked directly why they had chosen Norway as a destination, the responses indicate that it has been a deliberate choice for most respondents. Figure 1 shows that the most common answer was the good protection of their rights in Norway. One-third admitted that they had considered different countries and concluded that Norway was a good choice.

In an open survey question and via qualitative interviews with displaced individuals from Ukraine, those who had deliberately compared Norway to other countries before making their choice listed various reasons why Norway was preferred. Many highlighted positive qualities of Norway and Norwegian society, including the rule of law, democracy, a high standard of living and low levels of corruption. Favourable conditions for children’s development also ranked highly.

Figure 1: Self-reported reasons for coming to Norway

Note: There were 1,592 participants. Data weighted by age and gender.

Most displaced Ukrainians appreciate the introduction programme that they have the right to attend, with most attending for at least six months and usually longer. This programme provides them with an opportunity to learn Norwegian before entering the labour market while simultaneously receiving economic support from the state. However, authorities are increasingly emphasising that displaced Ukrainians should move faster into the labour market than has been the case so far, as participation rates are currently lower than in Norway’s neighbouring countries.

Ukrainian refugees see a lack of sufficient knowledge of the Norwegian language as their biggest obstacle to finding a suitable job and are motivated to learn the language first. Still, most are aware of the need to find a job that might not necessarily match their previous education and qualifications. When looking for work, they find that employers prefer, and many professions require, that they have a certain command of the Norwegian language.

Future prospects

There are several factors that make planning difficult and create uncertainty about the future of those displaced from Ukraine. These include how long the war will last and how long they will be allowed to stay in Norway.

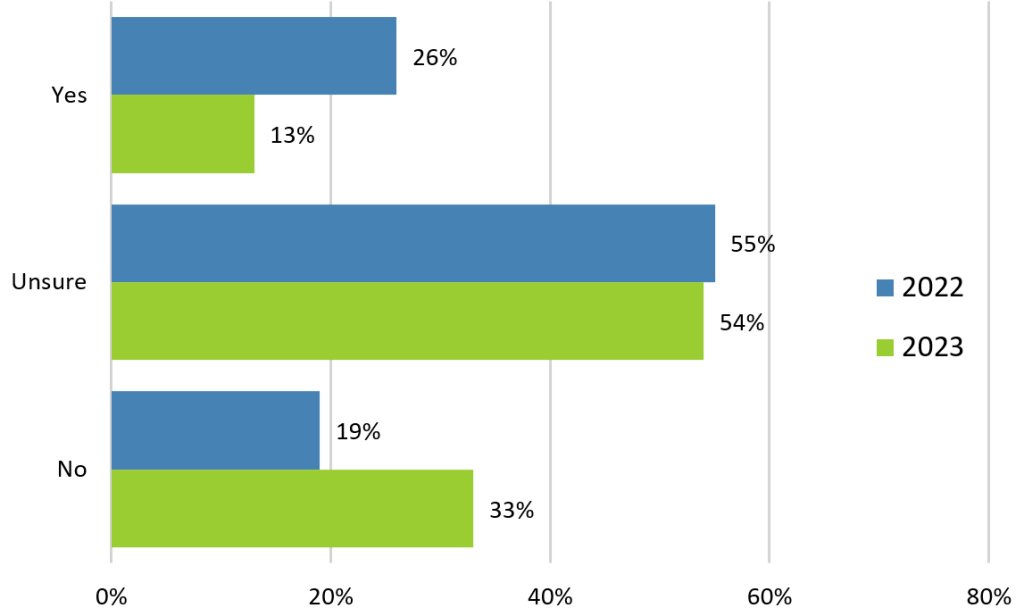

In the survey, fewer people now express a desire to return to Ukraine than was the case in a similar survey conducted in the summer of 2022, although the majority are still uncertain (see Figure 2). And increasingly, more Ukrainians believe that the war will last a long time. With the high arrival numbers, authorities are now emphasising more clearly that the stay of Ukrainians is meant to be temporary. Some politicians have also started discussing possibilities for a “safe return” to areas of Ukraine that have been less affected by Russian attacks.

Figure 2: Responses to the statement: “I will return to Ukraine as soon as the war ends”

Note: The figure shows a comparison of answers from surveys in June 2022 and December 2023. Data weighted by age and gender in both surveys.

Norwegian authorities underscore the importance of providing a welcoming environment for Ukrainians in Norway, a sentiment that is echoed in the survey findings, where Ukrainians express their mostly positive experiences in the country. However, uncertainty about the future creates dilemmas for both national and local authorities and for Ukrainians themselves. How much should be invested in securing qualifications and Norwegian language skills if Ukrainians are expected to return anyway?

By offering better conditions than other countries, Norway might continue to be an attractive destination, potentially straining the capacity of already burdened municipalities in the long run. On the other hand, if many Ukrainians are going to stay in Norway for an extended period, investing in their Norwegian language skills and qualifications would be a wise decision. In that case, displaced Ukrainians could make important contributions to a country where the demand for qualified labour is high.

Almost two years have passed since Russia’s full-scale invasion and soon there will be a need to find solutions for Ukrainians who were initially granted collective protection for up to three years. Norway will undoubtedly look to decisions made in other European countries with similar collective protection systems. Unfortunately, it seems that the need for protection will persist for a long time. For now, all stakeholders must balance various dilemmas and considerations as they consider their next move.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying report (co-authored with Vilde Hernes, Oleksandra Deineko, Marthe Handå Myhre, Tone Liodden, Trine Myrvold, Mariann Stærkebye Leirvik and Åsne Øygard Danielsen)

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Oleksandr Khokhlyuk / Shutterstock.com