Strikes have taken place in Finland against proposed labour reforms. Markku Sippola argues Finland’s current economic situation offers little justification for the reforms, which could have a significant impact on workers and the economy.

The Finnish government, led by Petteri Orpo, is currently implementing sweeping labour and social security reforms. These have been justified as a way to boost employment and competitiveness, but without genuine consultation with trade unions.

The changes include making it easier to dismiss employees, relaxing regulations on fixed-term contracts, making the first sick day a day without pay, reducing unemployment benefits, restricting political strikes, capping wage increases based on export sector wages and easing local bargaining. The unprecedented scale of change is reminiscent of the reforms pursued by Margaret Thatcher in the UK or by Portugal under pressure from the Troika in 2011. However, unlike those situations, Finland’s economic situation doesn’t necessitate such reforms.

The reforms have sparked massive strikes from Finnish trade unions, yet the government remains steadfast. This suggests a deliberate attempt to weaken union power. The government argues that the existing labour market structures have led to poor economic outcomes, with Finland having high unionisation rates and strong collective agreements.

While Finland has maintained low in-work poverty rates thanks to its centralised wage-setting system, employer associations see the latter as market rigidity. The government aims to not only reduce social security protections temporarily but also dismantle decades-long industrial relations structures.

Proposed changes include allowing non-union representatives for local bargaining, limiting political strikes, increasing penalties for participation in “illegal” strikes and reducing the national conciliator’s power to propose sector-level wage increases. These changes aim to undermine union legitimacy, discourage industrial actions and weaken the national conciliator’s role.

How bad is the economic situation in Finland?

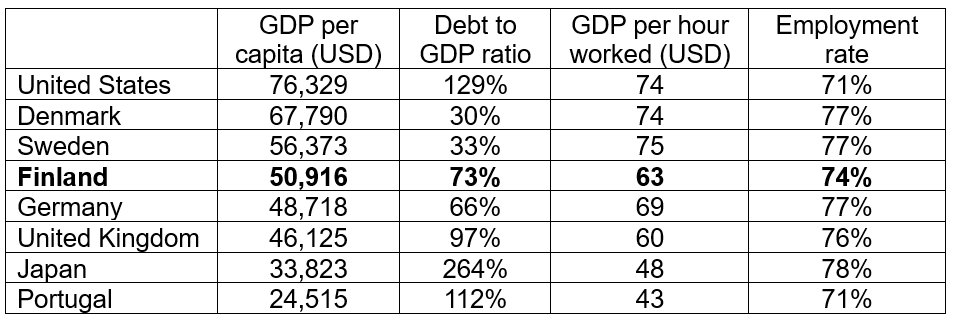

The economic situation in Finland is not as catastrophic as during the COVID-19 crisis. And while the government claims its reforms will boost competitiveness and employment, evidence is lacking. Current productivity and employment rates are moderate, and government debt, while growing, is not alarming (Table 1). The government has reacted to a growing budget deficit by cutting both taxes and social security, thus eroding the tax base.

Table 1: Key indicators for the Finnish economy compared to selected OECD countries

Note: All figures from 2022. Sources: GDP per capita: World Bank; Debt to GDP ratio: World Population Review; GDP per hour worked: OECD; Employment rate: OECD.

During the COVID-19 crisis, a tripartite effort, involving the government, employer associations and trade unions, helped mitigate economic distress. However, the current government is unilaterally pushing labour market reforms without meaningful dialogue. Comparisons with past European reforms suggest potential consequences for Finnish competitiveness and employment and should raise concerns about the future impact on workers and unions.

Lessons from the UK and Portugal

The current strikes in Finland have parallels with the UK’s “winter of discontent” during the 1970s, which led to Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power. Thatcher implemented stringent measures against unions, halving membership by the turn of the century. Her tough stance, epitomised by the 1984-1985 miners’ strike, earned her the nickname the “Iron Lady”. While her reforms slightly improved productivity and reduced inflation, they exacerbated inequalities and had minimal impact on unemployment.

Similarly, the Finnish government views unions as a threat to democracy and is imposing labour reforms that were not contained in the campaign pledges made by the governing parties at the last election in 2023. The government also plans to fine individuals and unions for participating in “unlawful” strikes, which were also a focus of Thatcher’s policies.

Portugal implemented reforms that were overseen by the Troika in the 2010s due to a fiscal imbalance and economic stagnation. These reforms included labour market changes like reduced severance payments and increased flexibility. Despite initial positive economic signs, the reforms prolonged the country’s recession and deregulated labour markets. However, after left-wing parties took power in 2015, the economy began to recover steadily with more pro-labour policies.

While initially successful, the Troika reforms did little to boost Portugal’s economy in the long run. Instead, returning to collective bargaining and prioritising well-protected employment since 2015 proved more beneficial. Though unionisation rates dropped, post-Troika Portugal shows how labour-hostile policies can be reversed for more positive economic and employment outcomes. This parallels the arguments behind Finland’s current labour reforms, although the outcomes differ significantly.

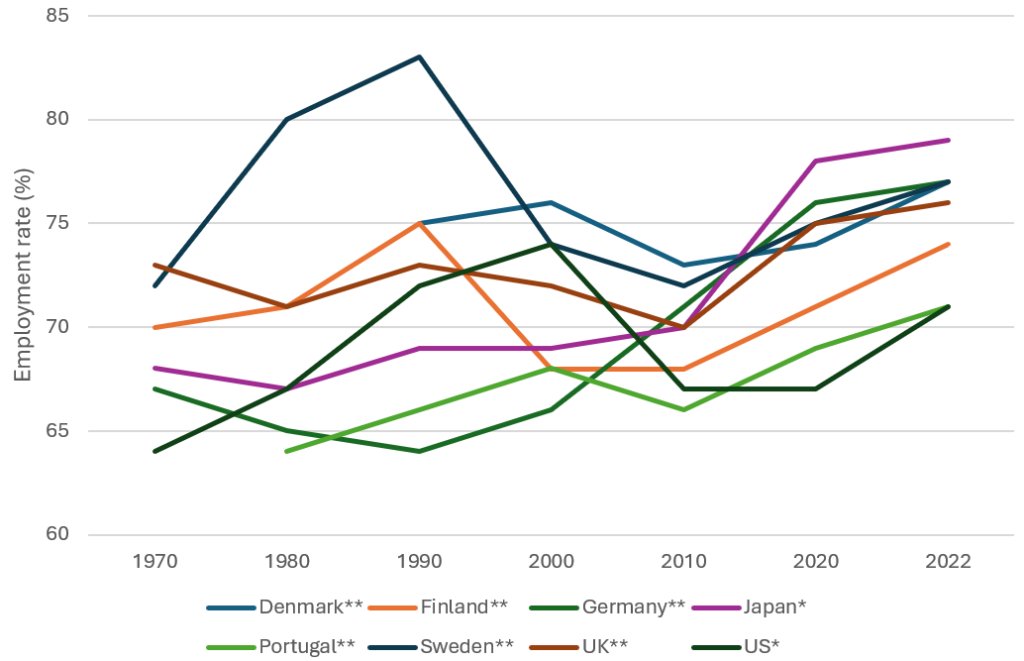

Employment and productivity trends do not show remarkable performance outcomes for the UK and Portugal during their respective reforms. As Figure 1 shows, Portugal has made significant progress on employment rates, but still lags behind the UK and Finland.

Figure 1: Employment rate in selected OECD countries

Note: OECD data for people aged 15-64.

Thatcher’s policies in the UK during the 1980s did not notably improve the employment rate. Sweden outperformed all countries in the 1980s, while Finland’s employment rate plummeted during the 1990s recession, but has since rebounded. Recent employment rate increases in Japan, Germany and the UK are attributed to the proliferation of low-paid jobs, leading to a rise in in-work poverty.

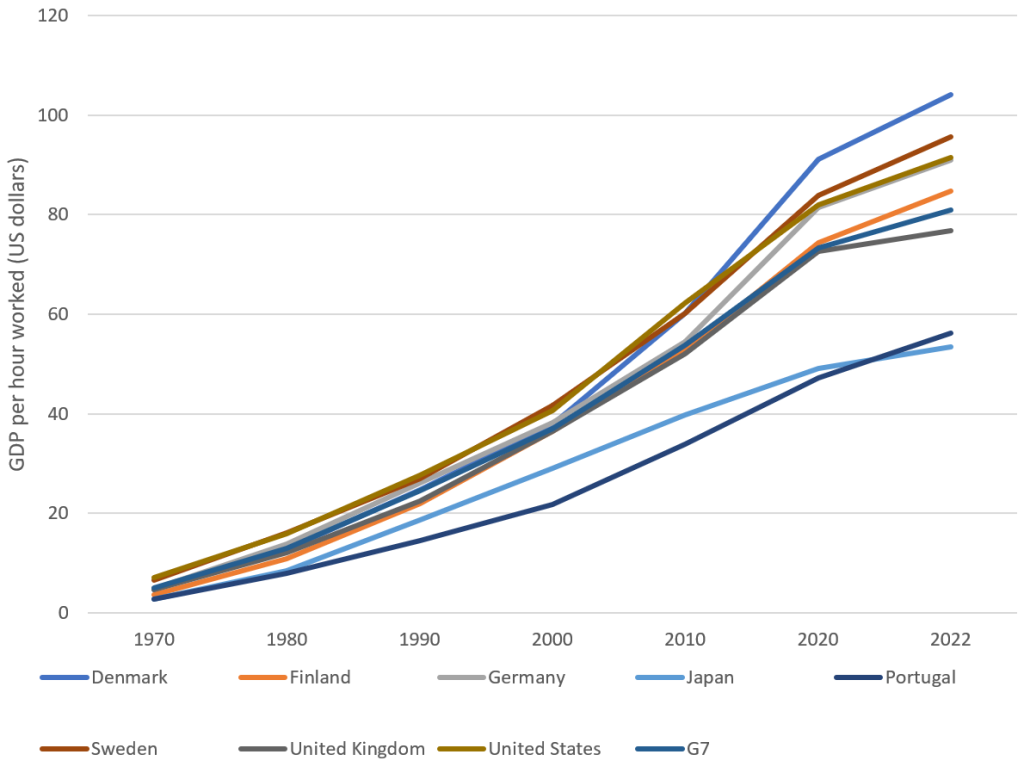

A similar picture emerges in relation to productivity. Productivity in Finland and the UK have followed similar trajectories since 1970, with Finland slightly outpacing the UK in recent years. Portugal’s productivity remained stagnant despite the Troika reforms from 2010 to 2014, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: GDP per hour worked in selected OECD countries

Note: Figures are in US dollars (current prices). Data from OECD.

The above comparison shows the Finnish government’s proposed labour and industrial relations reforms are unsustainable. Finland’s productivity and employment rates are already stable, negating the need for drastic measures. Analogous reforms in the UK and Portugal, driven by domestic and international pressures respectively, did not notably improve economic outcomes. Portugal saw some progress post-Troika reforms, while the UK’s employment increase was driven by a rise in low-paid jobs.

The government’s unilateral “shock-therapy” undermines unions and diverges from the gradual reform approach taken by neighbouring Nordic countries, where reforms involve labour market stakeholders. This unilateral attack on unions risks destabilising Finland’s relatively strong economic indicators, including low in-work poverty rates.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutterstock.com

How about the results of the EU Debt Sustainability Monitor? Finland has fallen into the category of Medium Term High Risk countries: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2024-03/ip271_1_Executive%20summary.pdf Structural measures to boost growth are needed to turn the trend in the debt/GDP ratio.

In Finland, there is a party in the government whose members have participated in summer camps of neo-Nazi movements, where they shoot at images of members from another party as targets. Ministers and the Speaker of the Parliament fantasize about shooting minorities, spread the great replacement conspiracy theory, and one minister declares themselves a Nazi. Another fantasizes about tar and feathering Ursula von der Leyen during her visit and sending her back. Such is the country of Finland.