Finland’s election on 2 April ended in defeat for Sanna Marin’s ruling Social Democrats, with the opposition National Coalition Party finishing in first place. Tapio Raunio reflects on the result of the election and assesses what might come next for Finland.

The parliamentary elections in Finland on 2 April were in many respects unusual. Putin’s war in Ukraine has had a dramatic impact on Finnish security policy, with Finland seeking NATO membership by mid-May 2022 and joining the defence alliance two days after the election on 4 April. NATO membership was accepted almost unanimously in the Eduskunta, the unicameral national legislature, and hence the dramatic change in the country’s security policy status hardly featured at all in the parliamentary elections. However, a few security and defence policy experts with strong media presences were elected to the parliament from the ranks of the National Coalition (conservatives).

The second deviation from normal patterns concerned pre-election promises. In Finland, it has been customary for parties and their leaders not to commit themselves to any potential coalitions nor to declare that they would not join a government with a particular party. However, citing differences in worldviews, this time around the three centre-left parties – the Social Democrats, the Green League, and the Left Alliance – each announced that they would not share power with the populist and anti-immigration Finns Party.

Also, the Swedish People’s Party made it clear that it would be difficult for the party to enter a cabinet together with the Finns. Interestingly, the Finns Party started out as a populist, Eurosceptic party that was quite centrist and even centre-left on the socio-economic dimension, but has since the 2010s moved in a more right-wing direction with opposition to immigration the central item on its agenda.

The third unusual pattern was the extremely high popularity and visibility of Prime Minister Sanna Marin, the leader of the Social Democrats. Marin, currently 37, has been touted as the ‘rock star’ of Finnish politics, and she is clearly the most famous Finnish politician of the 21st century. Marin and her left-leaning five-party government that brought together the Social Democrats, the Centre Party, the Green League, the Left Alliance, and the Swedish People’s Party – all parties chaired by women – have received a lot of international media coverage.

Marin is perhaps also a polarising figure, but her support has remained very strong throughout the early 2020s. Her popularity is also a major challenge for the Social Democrats, as Marin was probably a key factor in attracting younger voters to support the party. Three days after the elections Marin announced that she would step down as the party chair in the party congress in September. Her successor will face a very tough job in ensuring that younger voters continue to vote for SDP.

Marin’s government had steered the country through the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, but Finland has had to incur further debt in the process. The centre-right parties, particularly the National Coalition, therefore focused very much on getting the economy back on track.

Petteri Orpo, the party’s leader, declared a ‘6+3’ policy, meaning that the next government should reduce debt by six billion euros and the government after that by three billion euros. The Finns Party and the Centre Party broadly agreed with Orpo, while the leftist parties argued against radical cuts and favoured investments that would generate growth and employment. The National Coalition is internally split on the socio-cultural dimension, and hence this focus on the economy worked in the party’s favour.

Marin’s government had finally managed to agree on a reform of social and health services, a topic that had been on the agenda of several previous governments. As part of that package, Finland established directly-elected regional councils, with the first elections held in January 2022. The funding and quality of social and health services has raised serious concerns, but it was harder to detect major differences between the parties, although the left-wing parties underlined more the role of the state in providing such services.

Segregation among schools and students and internal security featured also in the campaigns, with the Finns Party connecting these issues to immigration, as in the months leading to the elections there were reports about problems in the education system and worsening street violence. Overall, the election debates focused to a large extent on state finances and the future of social and health services. In that respect, the campaign was almost like a throwback to the 1980s – the European Union was hardly mentioned, and socio-cultural issues, including climate change, remained firmly in the background.

The results

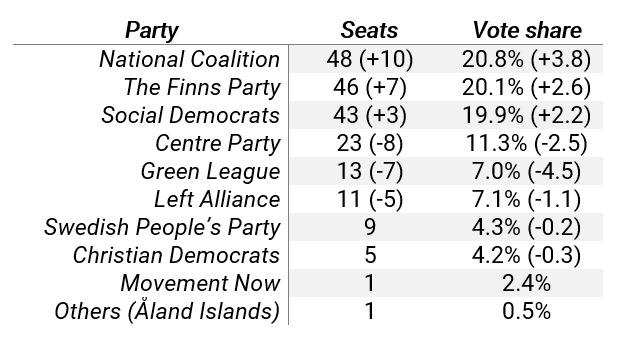

Orpo managed to guide the National Coalition to pole position, with 20.8% of the vote (+3.8) and 48 seats (+10). It is therefore Orpo who will lead the government formation talks. The difficult choice Orpo must make concerns coalition partners. The Finns Party finished second with 20.1% of the vote (+2.6) and 46 MPs (+7). The populists achieved a breakthrough in the 2011 elections and have finished in the top three in the elections held since. Most notably, the Finns Party won votes throughout the country, in urban centres as well as in rural areas.

The Finns Party was in government from 2015 to 2017, during which time its support dropped dramatically. Party leader Riikka Purra was the vote queen of the elections, with 42,594 votes in the Uusimaa district (the largest constituency). Since the 2011 elections, the Finns Party has been the largest party among working-class voters, yet the party remains critical of trade unions that continue to see the Social Democrats as their natural ally. The National Coalition and the Finns Party could easily agree about state finances, but the former is a solidly pro-EU party while the latter has even flirted with the long-term option of leaving the Union.

Table: Results of the 2023 Finnish parliamentary election

The Social Democrats came third with 19.9% of the vote (+2.2) and 43 seats (+3), an impressive result considering the party of the prime minister normally loses votes. There have been several coalition governments between the National Coalition and the Social Democrats since the 1980s, but the two parties disagree about economic policy.

During the election campaign, Marin engaged in aggressive rhetoric against the National Coalition and the other parties of the right. Specifically, she argued that voting for the SDP is the only way to prevent a victory for the political right. This did not go down well among the Greens and the Left Alliance, as the final campaign weeks focused very much on who would finish first and therefore take the lead in forming the new government – the National Coalition, the Finns Party, or the Social Democrats. Other parties received much less media attention, with especially the Greens finding it difficult to get their message across.

In Helsinki district, the Social Democrats increased their support by 7.3% to 20.9%, with the even larger drop in the support of the Green League suggesting that many Green voters switched to the Social Democrats in these elections. Party leaders Maria Ohisalo (Greens) and Li Andersson (Left Alliance) looked absolutely gutted as the election results became clear. The Greens won 7% of the vote (-4.5) and 13 seats (−7), while the Left Alliance received 7.1% of the vote (-1.1) and 11 seats (-5). What this implies for future cooperation between the left-wing parties remains to be seen, but it is safe to predict that the support of the Greens will increase again over the next few years – and this may happen at the expense of the Social Democrats.

The elections were a crushing blow for the Centre Party, which had led governments from 2003 to 2011 and from 2015 to 2019. The party suffered a humiliating defeat four years ago, and fared even worse this time round, with 11.3% (-2.5) and 23 seats (−8). The Centre had been the largest party in several rural electoral districts, but the Finns Party is now the biggest in those constituencies. It is likely that many Centre voters did not appreciate their party’s inclusion in the Marin cabinet, but nor did they seem to appreciate the ‘economy-first’ approach of the Centre-led cabinet in 2015-2019. Clearly a lot of soul-searching will take place in the party, and presumably under a new leader. The current party chair Annika Saarikko has vowed that the Centre would stay in the opposition.

Of the smaller parties, the Swedish People’s Party won 4.3% (-0.2) and retained its 10 seats (including the representative of the Åland Islands). The Christian Democrats won 4.2% of the vote (+0.3) and held on to its five seats. Movement Now, registered as a party in late 2019, won 2.4% of the vote and maintained its sole MP. Turnout was 72%, and it appears that turnout has stabilised at roughly that level in the elections held in the 21st century.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Union