Portugal stands on the brink of commemorating 50 years since its transformative “Carnation” revolution, which ushered in democracy. However, as João Almeida and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose explain, the current political climate casts a shadow over this milestone. The country’s recent general election spotlighted a disturbing trend: the rise of the far right. This surge is driven by the grievances of people living in overlooked regions of Portugal, people who after 50 years of democracy – in a move reminiscent of the “revenge of the places that don’t matter” elsewhere – seem to have given up on mainstream parties.

On 25 April this year, Portugal will celebrate 50 years since its democratic revolution – a revolution that ended 42 years of a far-right dictatorship and delivered democracy and far greater prosperity for the country. But this month, the general election in Portugal has marked a significant departure from the political status quo.

Chega (Enough), an extreme right-wing populist party, has made a massive breakthrough. The party has been catapulted from a single seat in 2019 to 12 seats in 2022 and now to a staggering 50 seats in 2024, in a parliament of 230 seats. The exponential rise of Chega has fractured the long-standing duopoly of the Socialist Party (PS) and the Social Democratic Party (PSD).

This seismic shift in Portuguese politics was not unexpected. It reflects a broader phenomenon observed across Europe, the United States and other parts of the world, where populism has gained momentum amidst social and economic turmoil. Recent rapid rises in populist support in Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and, to a lesser extent, Spain mirror developments in Portugal.

The rise of Chega can be attributed to a confluence of factors, including a sense of nostalgia for the country’s authoritarian past, disillusionment with corruption scandals plaguing the national and local governments, and a strategic and skilled use of social media to amplify their message and mobilise people who in previous elections felt disenfranchised by the political options on offer. However, perhaps most crucially, this phenomenon is deeply rooted in what scholars have termed the “geography of discontent”.

The geography of discontent in Portugal

The populist surge in Europe reflects what has become known as the “revenge of the places that don’t matter”. This phrase refers to places that have been locked out of economic development and exhibit increasing forms of long-term social exclusion and deprivation. At its core, the “geography of discontent” captures the frustrations of communities left behind by economic progress. It particularly reflects the growing exasperation of those residing in long-term declining, often rural areas and smaller towns, grappling with stagnation, declining public and private services and limited opportunities.

Portugal has not been immune to these geographical trends. Portugal remains one of the most centralised countries in Europe, economically, in terms of infrastructure, and politically, where the inland districts represent two-thirds of the area of mainland Portugal, but elect fewer MPs than the Lisbon capital district alone.

Portugal’s socio-economic landscape is also marked by profound regional disparities, with the country’s hinterlands bearing the brunt of economic marginalisation and social exclusion. These peripheral regions have fallen behind in terms of investment, infrastructure and employment prospects, thus becoming fertile ground for populism and far-right ideologies.

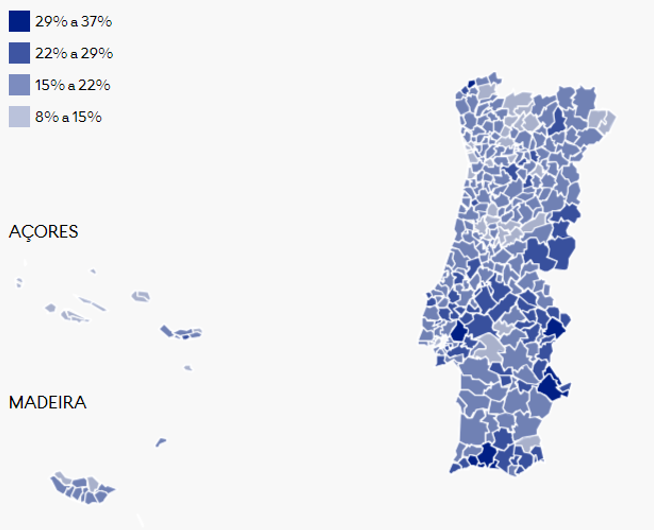

In a 2021 study, it was found that Chega supporters are more likely to live in rural rather than in urban areas. The recent election results confirmed this pattern. The party’s strongholds are rural areas and some medium-sized cities, where feelings of marginalisation and neglect run deep. Despite overall growth in all municipalities, Chega struggled to make inroads in urban centres, drawing attention to a growing gulf between Portugal’s metropolitan hubs and its peripheries.

In rural areas, Chega’s vote went from 10.92% to 36.53% of the total. Chega also secured MPs in every electoral district except Bragança. Chega even surpassed both the left-wing Socialist Party (PS) and the right-wing Democratic Alliance (AD) in the region of Algarve and in many municipalities of the rural Alentejo region, where the Communist Party traditionally was the main force.

More surprisingly, it also came first in the foreign vote (with a significant contribution by Portuguese migrants in Switzerland and Luxembourg). In contrast, Chega performed far worse in big cities, with its share of the vote being less than 10% in Porto, Portugal’s second city (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage vote share for Chega by municipality in the 2024 Portuguese general election

Source: Expresso.

Many opinion-makers have argued that a large share of Chega’s voters do not necessarily agree with the party’s programme, but rather that their vote is a form of expressing their discontent against the traditional parties and of revolting against the status quo.

The case of Algarve is paradigmatic. It is Portugal’s main tourist hub with a GDP per capita higher than the national average. But it is also a region with a strong social divide and with lower salaries and a higher poverty rate than the national average. According to a Portuguese journalist, “Algarve is the culmination of disenfranchisement. It’s a region that feels forgotten by the two parties that have governed the country, that feels placed further and further away from Lisbon and that, because its inhabitants feel their problems are neglected, has turned to Chega not even as a protest vote, but as a useful vote.”

A note on turnout and youth mobilisation

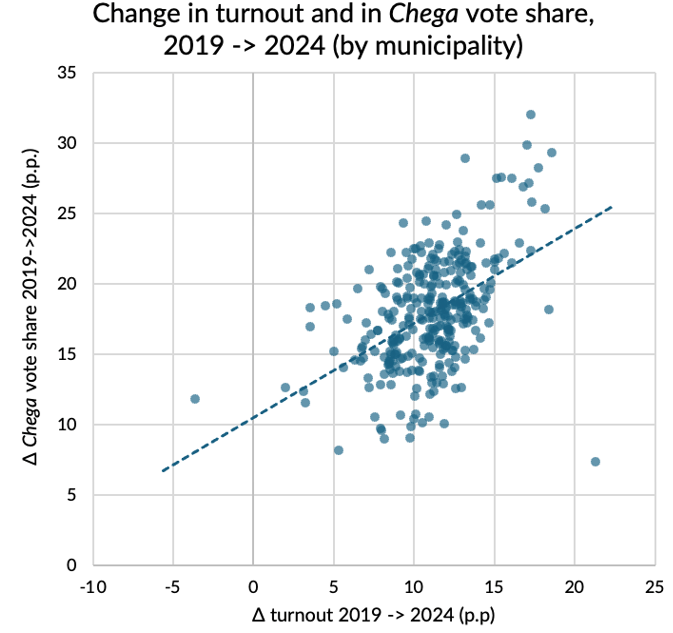

The 8.4 percentage point increase in voter turnout in the 2024 election – which particularly mobilised young voters – is another key determinant of Chega’s electoral success. The decrease in abstention appears to be strongly correlated with the growth of the radical right. Chega’s strong support among young people (especially men) reflects a desire for change and a rejection of the political establishment, underscoring the effectiveness of populist narratives in mobilising support among disenchanted segments of society.

Figure 2: Correlation between change in turnout and Chega vote share

Source: João Cancela (NOVA FCSH) and Pedro Magalhães (ICS-ULisboa).

Lessons for the future

Portugal is no longer an exception in the European political panorama. Given what has happened in the national elections, in the forthcoming June European elections Portugal is expected to join the growing number of European countries that shift towards the political extremes and populism. This will add to the growing challenge European institutions are facing to continue building the European project.

As Portugal wanders into this new political reality, policymakers must heed the lessons learned from this election. Addressing the root causes fuelling this discontent, rather than merely treating its symptoms, is paramount to fostering social cohesion and expanding the opportunities in left-behind places. This calls for a more comprehensive approach that includes place-sensitive policies, empowers local communities and fosters dialogue across political divides.

The rise of far-right politics in Portugal serves as a reminder of the challenges facing modern democracies. The new Portuguese Government, and especially, the next Ministry and Secretaries of State for Territorial Cohesion and Regional Development, must understand the underlying dynamics driving this phenomenon, and their role in paving the way towards a more resilient and inclusive Portugal, where the voices of all citizens, irrespective of where they live in the country, are heard and valued.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Jose Pablo Bravo / Shutterstock.com

The same happened in Argentina.

All of this was already foreseeable from the start of Chega in 2019…

And nothing was done to prevent it.

https://www.scielo.br/j/cm/a/pwf5mpjSBzQww5ZYgrpdMfv/?format=pdf&lang=en

Perhaps the voters have had enough (chega) of the “Extreme” Left.

Why must the word “extreme” right be used to describe anyone who doesn’t agree with everything liberal? Facism requires a dictator; no one wants a dictatorship.