Belgium will hold simultaneous federal, regional and European elections on 9 June. Philippe Mongrain and Karolin Soontjens preview the vote, writing that while it is difficult to predict the outcome, the tide seems to have turned in favour of more radical parties.

This article is part of a series on the 2024 European Parliament elections. The EUROPP blog will also be co-hosting a panel discussion on the elections at LSE on 6 June.

On 9 June, Belgians will head to the polls for the first time in five years, making this the longest period without any parliamentary elections since the Second World War. Voters will cast their ballots for members of the regional, federal and European parliaments.

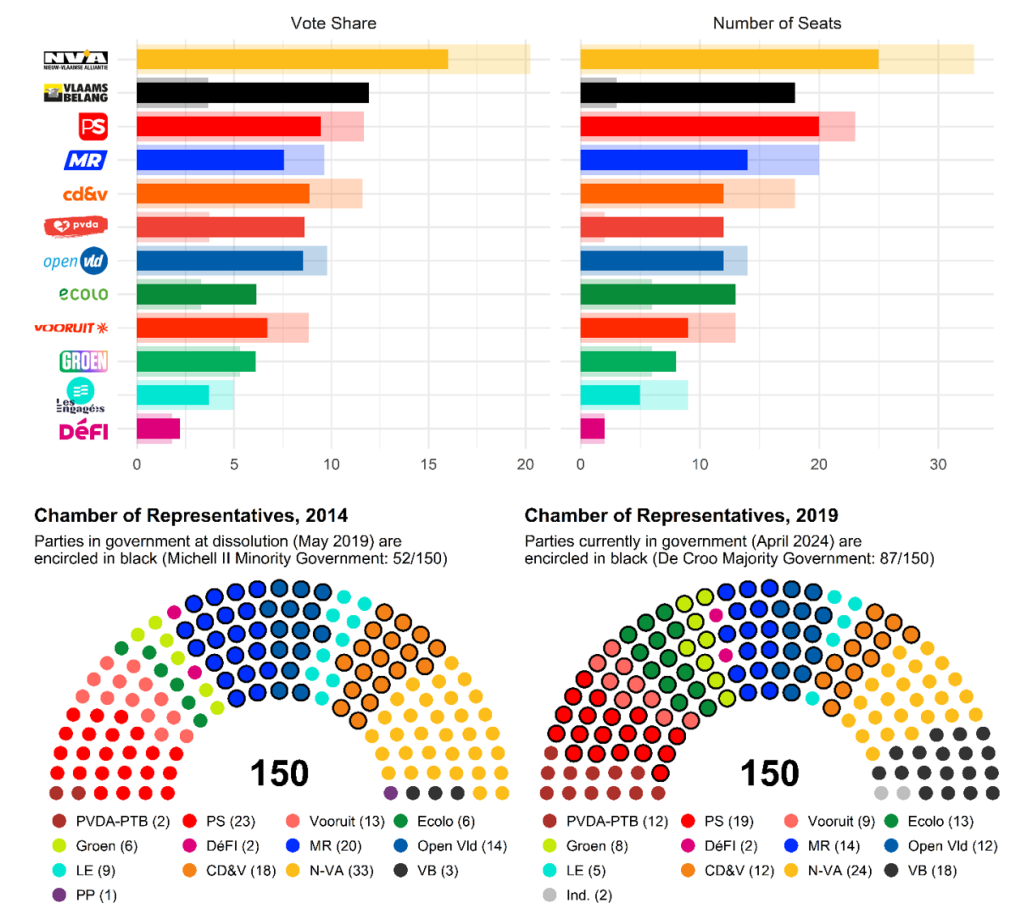

During the last federal elections in 2019, we witnessed a weakening of the ruling parties (N-VA, MR, Open Vld, CD&V) and, more generally, of traditional party families. Liberals (Open Vld, MR), Social Democrats (SP.A/Vooruit, PS) and Christian Democrats (CD&V, cdH/LE) gathered less than 50 percent of the vote, a first since the Second Word War (see Figure 1).

The decline of these party factions primarily benefited more radical alternatives on both sides of the ideological spectrum. Vlaams Belang (VB), a Flemish nationalist and right-wing populist party that advocates for the independence of Flanders and stricter immigration policies, managed to significantly increase its presence in parliament, gaining 18 seats in 2019 compared to just three in 2014.

On the far left, the communist Workers’ Party of Belgium (PVDA-PTB) gained 12 seats, up from only two in 2014. It appears that Vlaams Belang was able to attract mostly previous N-VA supporters – despite the latter’s efforts to prevent voters from shifting to the far right by adopting a tougher stance on immigration. Meanwhile, the PVDA-PTB mostly appealed to former SP.A (now Vooruit) and Groen supporters in Flanders, as well as Socialist (PS) voters in Wallonia and Brussels.

Figure 1: Results of the 2014 and 2019 Belgian federal elections

Note: Data from IBZ – SPF Intérieur. Semi-transparent bars show 2014 results. Solid bars show 2019 results. DéFI was formerly known as FDF, Les Engagés (LE) as cdH, and Vooruit as sp.a.

The outcome of the 2019 federal elections further exacerbated the divergence between an already more right-leaning Flanders and more left-leaning Wallonia. The election results largely mirrored the policy priorities in each region, with immigration being higher on the public agenda in Flanders, while socioeconomic issues were the top issues among Walloon voters. Moreover, the growth of extreme parties and the refusal of mainstream parties to govern with the far right (as part of the “cordon sanitaire”) have significantly complicated the government formation process.

Following the collapse of the Michel government in December 2018 due to the N-VA’s opposition to the Global Compact for Migration, the country went through 652 days of temporary arrangements and caretaker governments. Since October 2020, Belgium has been governed by a coalition of seven parties (the so-called “Vivaldi” coalition) – excluding the two largest parties in Flanders, the N-VA and VB – with Alexander De Croo, leading figure of the Open Vld, as prime minister.

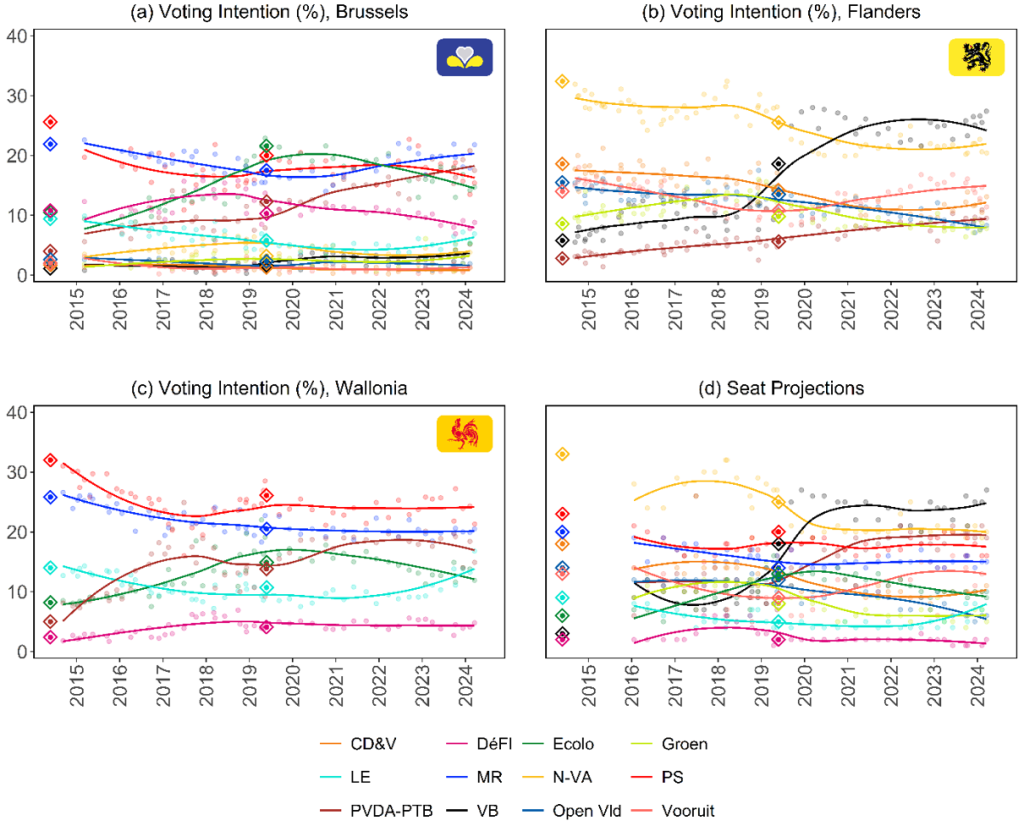

Most polls conducted after the 2019 elections have shown Vlaams Belang ahead of the N-VA by a few points in terms of vote intentions (see Figure 2). This marks an important shift from the 2014–2019 election cycle during which the N-VA was by far the largest party. Recent polls suggest that Vlaams Belang would secure at least a quarter of the votes in Flanders, translating to approximately 25 seats in the federal Chamber of Representatives if elections were held today, making it the largest party in parliament.

Figure 2: Voting intention and seat projections for the Belgian federal elections (May 2014 – March 2024)

Note: Data from Wikipedia. Semi-transparent markers represent individual polls. Trend lines are local regressions (losses). Diamond-framed markers show the actual vote share/number of seats won by each party on election day.

The three Flemish centre-right formations (CD&V, N-VA and Open Vld) as well as the Greens are experiencing a (large) decline in support compared to the previous elections. This expected loss of support is greatest for the prime minister’s party (Open Vld), for which the polls predict an historically low result of around eight percent.

For a long time, the polls were much more positive for the centre-left party Vooruit, which was polling at over 16 percent last year. Recently, though, the polls report much lower support, following controversies surrounding its former chairman, Conner Rousseau, who resigned over racist remarks in November 2023. Vooruit now finds itself almost neck-and-neck with the CD&V at approximately 11 percent.

However, Rousseau has recently announced his comeback and will be actively involved in the campaign, hoping to reverse the recent negative trend in the polls. While the progression of the Flemish socialists has been halted, the PVDA appears to be gaining new supporters in Flanders: around 10 percent of Flemish voters say they intend to vote for the PVDA, twice its score in the previous federal election. In fact, communists are making headway in all three regions, with support for the PVDA-PTB hovering around 16-18 percent in Wallonia and Brussels.

The Socialist Party (PS) continues to lead vote intention polls in Wallonia, closely followed by the liberal Mouvement Réformateur (MR), which currently holds the top position in Brussels. The centrist Les Engagés (LE) is also improving its score among voters in both Wallonia and Brussels, while Ecolo appears to be losing support in both regions.

Government formation

These polls hint at a complicated government formation process, mainly because the rise of extreme parties (PVDA-PTB and Vlaams Belang) makes it challenging to form governments with a limited number of mainstream parties. All parties explicitly refute the possibility of forming a government with Vlaams Belang – except for some N-VA politicians who have declared their willingness to break the cordon sanitaire. In addition, most parties have stated they would refuse any coalition agreement with the PVDA-PTB.

In most polls, the current federal Vivaldi coalition maintains a majority, albeit only in Brussels and Wallonia. Hence, Vivaldi II might be possible, but the dynamics between the current Vivaldi parties would shift substantially, with Open Vld taking a much weaker position and vice versa for the socialist parties.

Another coalition that sporadically gains majority support in the polls is the so-called “Burgundian coalition” with the N-VA, liberals (MR and Open Vld) and socialists (PS and Vooruit), perhaps with the Christian Democrats too. However, the enthusiasm for such a large coalition seems low.

An alternative possibility is forming a federal minority cabinet. The N-VA for instance has advocated for such a minority government with the socialists – possibly securing around 55-60 seats. However, it is hard to see why socialists, especially the PS in Wallonia which is losing voters to the PTB, would be in favour of such a set-up. The PS would rather lean towards a left-wing government including socialists, greens, communists and Christian Democrats. This kind of federal coalition would have a substantial majority in Brussels and Wallonia, but not in Flanders. Plus, it is highly uncertain whether the Christian Democrats are willing to govern with the communists in the first place.

With over a month remaining before Belgians head to the polls, one can only be cautious about making electoral forecasts. Nonetheless, it seems relatively safe to say that, over the past years, the tide seems to have turned in favour of more radical parties, mirroring recent trends in other European countries and leaving traditional mainstream parties in decline. This is particularly true for Vlaams Belang, which can look at the recent success of the Dutch far-right PVV party in 2023 as a rather good omen.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutterstock.com