What are the implications of the upcoming U.S Presidential elections for progressive politics? Peter A. Hall argues that the contest will be run against a background of a country divided along party lines and a public that is deeply distrustful of the government. This distrust, combined with a recessionary ethic of “everyone for themselves”, which contrasts sharply with progressives’ appeals for ‘fairness’ mean that Europe should keep a close eye on the election race and its outcome.

What are the implications of the upcoming U.S Presidential elections for progressive politics? Peter A. Hall argues that the contest will be run against a background of a country divided along party lines and a public that is deeply distrustful of the government. This distrust, combined with a recessionary ethic of “everyone for themselves”, which contrasts sharply with progressives’ appeals for ‘fairness’ mean that Europe should keep a close eye on the election race and its outcome.

The American elections this November are full of implications for the future of progressive politics, both in the U.S and for those watching from Europe. The electorate will choose between two sharply discrepant visions of the future of American governance. On one side, the Democrats led by Barack Obama, while highly centrist, see the federal government as an important agent for improving the well-being of the population. On the other, a Republican Party dominated by the Tea Party movement portrays government as the problem rather than the solution and seeks radical reductions in the resources and jurisdiction of the federal government.

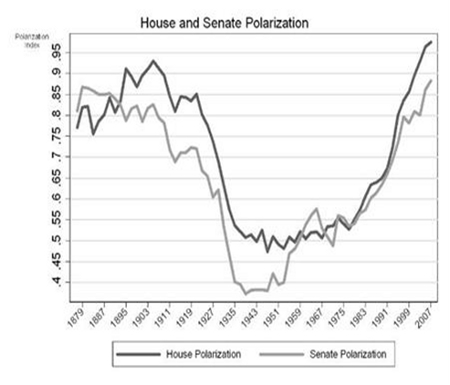

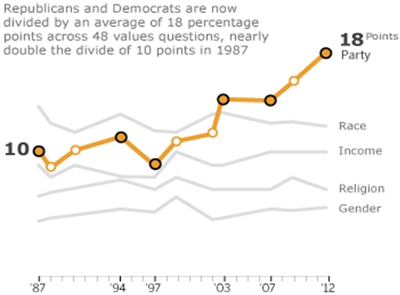

On these issues, the American republic is bitterly divided. In the U.S. Congress, party polarization (Figure 1) is at an all-time high, and recent polls (Figure 2), from the indispensable Pew Research Center show that the gap in views between registered Democrats and Republicans is also wider than it has been in 25 years.

Figure 1

Figure 2

This titanic clash crystallizes in the budget debate where Republicans want to close the looming deficit with radical cuts in spending, while the Democrats are willing to see taxes increase, though they are often not willing to advocate strongly for them.

Much is at stake. The public infrastructure of the country is in disrepair. Government spending on research and development and the education vital to innovation is stagnant. The standing of the dollar as a reserve currency turns on the ability of the government to close its deficit over the medium-term. On how it does so turns the country’s ability to maintain even a minimal social safety net. In short, Americans are about to decide whether they are willing to pay for the kind of government crucial to an advanced economy, let alone one capable of economic leadership in the world.

What are the prospects that Americans will make the more progressive choice? Current economic developments suggest Americans should be open to progressive political appeals. Income inequality has increased dramatically, especially at the top of the distribution. Unemployment is at a stubborn 9 percent and 16 million homeowners are underwater. Many Americans are wondering why the banks were bailed out when they were not. The irony, of course, is that this is not especially good news for President Obama whom many blame for the poor performance of the economy.

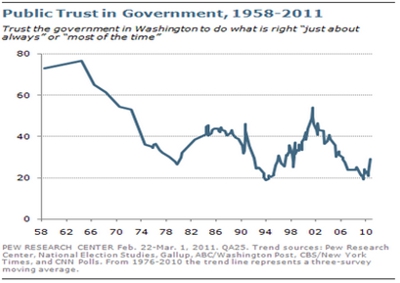

However, three other trends complicate this picture. The first is a longstanding American skepticism about the capacities of government, intensified in recent years by a decline in trust in government, shown in Figure 3 below. As a result, even if they want a better economic future, many Americans are unwilling to trust the federal government to help them secure it. The result is a vicious circle in which the public’s unwillingness to trust resources to government makes it difficult for governments to cope with the country’s problems, thereby confirming their view that government is ineffective. Breaking this vicious circle is one of the principal challenges facing political progressives in the US.

Figure 3

The sauve-qui-peut (“every one for themselves”) politics of recession is also salient. We are seeing a two-thirds/one-third recovery from which many people have been left out. Some suffer from what Barbara Ehrenreich has called a ‘fear of falling’ – of losing that middle-class status for which they worked so hard. This can make people less generous about redistribution. As Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky have noted, people are typically more concerned about what they might lose than what they might gain. Thus, in hard economic times, even those who might benefit from federal programs are often hostile to the taxes needed to pay for them. They want to hold onto what they have, lest the government give their resources away to others.

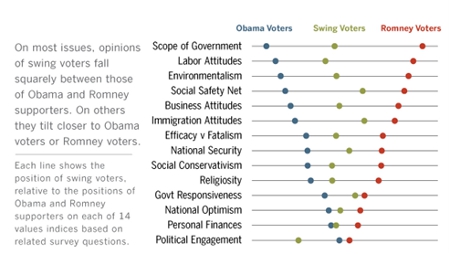

There is some evidence for this in recent surveys (shown in Figure 4 below) which show that Republicans and Democrats are most divided, not on the issues of morality or religion sometimes said to draw working class voters to the Republicans, but on issues of redistribution, and Independents tend to be closer to the Republicans on such issues.

Figure 4

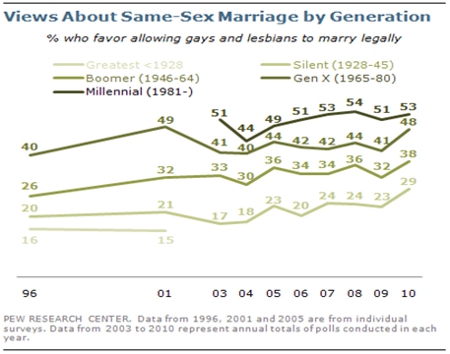

Offering more hope for progressives perhaps is the emergence of a generational cleavage. It shows up, first, in the fact that younger Americans are more liberal on social issues, such as gay marriage (Figure 5), abortion, race relations. Year by year, America is becoming a more tolerant society as younger cohorts replace older ones.

Figure 5

It is visible, too, in controversy surrounding the Affordable Healthcare Act, otherwise known as Obamacare. That Act is strongly opposed by the Tea Party movement, whose members are disproportionately drawn from older age cohorts. Why? Because they think, rightly, that Obamacare is going to fund the extension of benefits to the uninsured, many of whom are young families, by reducing spending on Medicare, the healthcare program for the elderly. So, while the Tea Party is full of contradictions, in some measure, it is a movement to retain benefits for the elderly at the expense of the young.

How these factors will play out in the November elections is far from clear. The Democrats are especially vulnerable in the Senate, where 21 Democratic and only 10 Republican seats are in play, and handicapped by the 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United that allows the wealthy to devote unlimited resources to the campaign. The Republicans are currently raising funds at a faster rate than the Democrats. But this election pits a community organizer against a specialist in private equity, and the Republican candidate embodies the positions of the wealthy at a time when many Americans have reason to resent their privileges.

Although American progressives operate in a very different context, where distrust of the state is endemic, European social democrats have reason to watch this election closely. Like recent elections in Europe, it is a contest between those seeking to exploit the sauve-qui-peut politics of recession and those who believe that resentment inspired by recession will fuel an appeal for ‘fairness’ – presented as the defining feature of an intergenerational social contract reminiscent of the principles of social citizenship espoused so famously at the LSE by T.H. Marshall. More than most elections, this is a battle for the hopes and fears of ordinary Americans and it will tell us much about the prospects for politics in hard times in Europe as well as America.

This post is drawn from remarks made to a July 4th symposium at the LSE sponsored by the Policy Network on ‘Lost or Anew: American Progressive Liberalism and European Social Democracy’.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/NiZZyY

_______________________________

Peter A. Hall – Harvard University

Peter A. Hall – Harvard University

Peter A. Hall is Krupp Foundation Professor of European Studies at the Department of Government, at Harvard University. Most recently Hall is co-editor of Successful Societies: How Institutions and Culture Affect Health, with M. Lamont (CUP, 2009), and a forthcoming volume (also with Lamont) Social Resilience in the Neo-Liberal Era (CUP 2013). He is the author of over seventy articles on European politics, public policy-making, and comparative political economy. He serves on the editorial boards of many journals and the advisory boards of several European institutes. He is currently working on the Eurocrisis, the political response to economic challenges in postwar Europe, and the impact of social relations on inequalities in health.