While some scholars recommend to follow official channels when conducting social science research in contemporary China, it is also acknowledged that research permissions are not always necessary in a number of cases. However, as the boundary between sensitive (mingan) and insensitive issues is not always graspable a priori, and authorities’ control over particular objects or places can also intensify, fieldworkers may sometimes have to deal with relatively unexpected difficulties, writes Lisa Richaud.

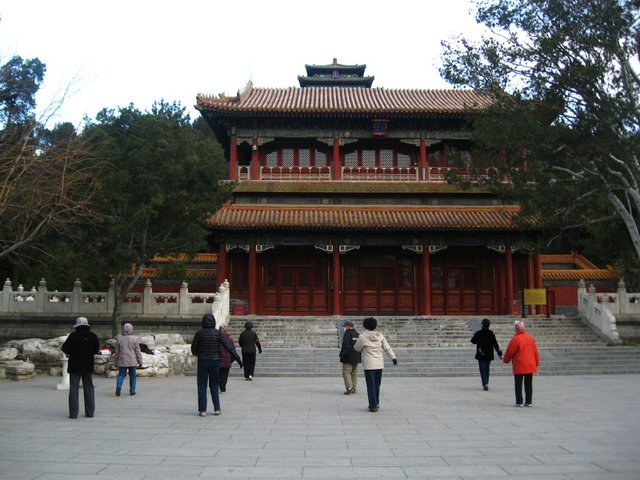

In this article, I reflect upon a recent experience of police intrusion and ongoing surveillance by security guards encountered during my fieldwork in Jingshan Gongyuan, one of the well-known public parks in Beijing and a former imperial garden. Relying on ethnographic accounts, I aim to depict and analyse the Chinese authorities’ control over fieldworker’s movements as a particular form of constraints that may have both practical and psychological consequences and therefore influencing one’s methods of field research.

How It All Began

“On Sunday afternoon, I am sitting on a bench in the north-western corner of Jingshan Park, where ‘political discussions’ are often going on. I am having a discussion with Mrs. W., a retired woman in her sixties who spend most of her afternoons in the park, and another Maoist nostalgic of the Cultural Revolution, who asks me about disorder to be brought by electoral systems if adopted in China. Without much caution, I engage in the discussion. As we are talking, I turn around and see a security guard leaning against the tree right behind our bench, overtly watching us. When the latter leaves, the Mmaoist notes without showing any concern that the guard was listening to us and suddenly left. I cannot remember how much time passed until two policemen arrive, probably long enough to make me forget about the guard, but sufficiently little to make me think that they acted rapidly. ‘This is for the Foreign Affair Department.’ One of the two men in uniform speaks to me in English, and the other holds a small camera and record the scene while the circle of people surrounding us grows rapidly. The Policeman inquires in a robotic tone: ‘Please show your passport’, ‘What is you nationality’, ‘Please write down your name’, ‘Please write down your passport number’, ‘When did you arrive in China’, ‘Please write down your visa number’, ‘At which hotel do you stay’, and ‘What is the purpose of your stay in China?’ I answer in Mandarin.” (Fieldnotes, 27 May 2012)

This scene occurred in Jingshan Park (Jingshan Gongyuan) in the middle of my second round of fieldwork, carried out from early May to July 2012, as part of my doctoral research on public parks in Beijing.

During an earlier stay in the winter, I often went to the north-western corner of Jingshan Park to observe discussions (liaotian’r) of self-labeled Maoist and liberal informal groups. There, in several occasions, I was filmed by policemen in civilian clothes (bianyi jingcha) who, with mobile phones in hand, would go around from one small gathering to another, record scenes, and listen to ongoing political conversations.

Previously, however, surveillance over my activities never exceeded anything more than silent note-taking of my presence by plain-clothes policemen (bianyi). Political expression in public may obviously be regarded as a sensitive (mingan) object in Chinese contexts. I was aware that I had been noticed by the local authorities. Nonetheless, it did not have direct impacts upon my access to the field, and this made me confident enough to continue my observation of the use of the public park as a place for political debates. I then thought that the situation could remain stable as long as the boundary was “trampled upon but still uncrossed” (cai xian bu yue xian, Ying, 2001). Thus, when I returned with a tourist visa to the field a few months later for conducting my research still outside official channels, I did not worry too much about potential obstacles. Here, I neglected the facts that it is often not easy in China to anticipate the moment when what was usually possible becomes no longer tolerated and that the boundary itself turns out graspable only after it has been crossed. Besides, particular political events may influence the shifting of the boundary: My second round of fieldwork was carried out just a few months after the Bo Xilai affair, which also had observable influence on the gatherings in the Jingshan Park and surely rendered my presence there even more mingan.

Somewhat ironically, the intrusion aforementioned in my filed notes occurred at a point of my fieldwork when my interest was shifting from the most visibly and self-claimed political use of the park to more mundane forms of gatherings and interactions in public. Thus, until it actually happened, I did not feel the need to make my presence official, and therefore felt legitimate as a regular park user myself. After the first serious encounter with the authorities, I was followed by several security guards (bao’an) and plain-clothes policemen (bianyi). Few days later when I returned to the park, I had to face another interview with two other policemen during which time they took photographs of my passport and visa. I then avowed the reason for my daily presence in the park, which is to collect some material for my doctoral research. Despite their promise that I shall not be followed again, I was still put under surveillance by the bao’an and bianyi almost every time I went to the Jingshan Park, and all this happened when I was observing what can be considered as the most ordinary and apolitical activities (Farquhar, 2009). While the security guards (bao’an) were the same few men every day, the plain-clothes policemen watching and following me around were always different; all males, different day after day, sometimes even within one afternoon.

It is hard to determine whether I had actually been held suspicious of anything after the successive police interrogations and if so, whether the authorities’ suspicion remained unchanged throughout the entire month I kept being followed. Were my watchers merely playing their part without much intention or conviction in the end? Was their presence made to warn me of any potential sanction that I could be disposed to in case of transgressions? Were the security guards just obeying an order from above or acting on their own decision?

Mrs. W., the woman aforementioned in my field notes, once told me that she heard the policemen talk about a “foreign spy”or “journalist” who revealed the existence of the political gatherings in the Jingshan Park. The authorities thus could have suspected me to be the said person. Be it a mere rumour or not, their suspicion could have risen by other factors, too; such as the regularity of my visits to the Jingshan Park and my familiarity with park users.

To date, I have not found any answers to the previous questions, and it is probably to no avail to try to find the intentions and motivations underlying the behaviours of the actors involved, especially given that most of my interactions with the security guards and plain-clothes policemen remained non-verbal. Thus, I rather present and analyse here, in an autoethnographic mode, the particular configuration of my fieldwork as a situation in which an ethnographer deals with constraints and at the same time, negotiates her role in place. Interactionist literature, regarding surveillance on researcher’s behaviours, shows that when authorities impose a new definition of a certain situation to which a field researcher has to attune, the interactions between the watcher and the observed allow some space for the researcher to pursue her work (Goffman, 1959). The modes of engaging in my own usual fieldwork activities were ambivalent as they were a kind of attempts to sustain my own definition of the situation and at the same time, the indication of my inability to refrain from acting innocent before my audience. This, in turn, proves my internalisation of the power relationships.

The Observed Observer: the Presentation of Self and Role Embracement

“Three days after the interrogation, I returned to the park. As I came close to one of the windows at the ticket office, a woman who sells entrance tickets looked at me, rose from her seat and joined some men standing in the back of the room. They, in turn, looked at me. I then went to the other window and purchased my ticket, convinced that the woman was warning others of my arrival. During the previous weeks, coming to the park was like entering a familiar territory in which I felt known and welcome. Now, I had an impression of myself being intrusive as if I were violating a tacit interdiction. I felt that I was overtly acting like a stranger and a foreigner, overplaying my role and exaggerating my interest even in some most mundane situations, in efforts to act as if nothing ever happened. I would go close to a group of women dancing in line, and watch them for a while, being conscious of myself pretending to watch them. My mind was too busy trying to find whether I was followed or not. I already experienced a similar feeling on Sunday afternoon as I was watching some Model Opera (yangbanxi) performers after the interrogation. Although observing such activities had been part of my fieldwork routine until then, I just ended up feeling that I was trying hard to deceive those watching me and endeavour to act innocently despite the fact that I was not guilty of anything in the first place.” (Fieldnotes, 31 May 2012)

What was peculiar about the constraints that I had to deal with was that no restriction had ever been explicitly formulated against me, which made my presence in the park still possible, but imbued it with a feeling of being unwelcome.

The strongest and most permanent discomfort which followed me since the first encounter with the police and the first experience of surveillance was to make me feel utterly visible. Like most public places in China, Jingshan Park is equipped with a thorough surveillance system, consisting of cameras displayed in the pathways, squares and corners of the park. Thus, even in the rare occasions when I was not obviously followed, I continuously felt potentially observed and noticed, which made me keep acting, conveying “signs of role embracement” (Goffman, 1972). I vainly hoped that it could make me appear innocent. Somewhat naively, I have never abandoned the hope to be able to work without surveillance again although obviously, I knew that my attempts to act innocent would not appear innocent in the eyes of my audience.

On the one hand, acting innocent turned out to be a difficult task, especially asI believed myself to be innocent at least in proportion to the intensity of the surveillance that indicates how strong the suspicion held against me was. On the other hand, surveillance always reminded me that to a certain extent, I might have trespassed upon the boundaries of what is acceptable, or was likely to cross the limit. Hence, I came to feel guilty of merely being there, which caused me to have difficulties in working with my full attention. As shown in the field notes above, one of the difficulties ethnographers face is that they pursue their tasks while feeling that they are faking their own role. Under the newly-defined situation, I somewhat came to internalise not only the constraint imposed by the very fact of being watched but also another role to which I was ascribed through such surveillance; that is, the role to play as an outsider or someone potentially pursuing illegal activities.

As the great majority of my interactions with security guards (bao’an) and plain-clothes policemen (bianyi) remained non-verbal, I recounted in an autoethnographic mode how I felt while attempting to embrace different kinds of roles in such interactions through facial and bodily expressions and also by means of engaging in other park-goers’ activities. The distance observed by the men to watch me ranged from less than one meter to several, but no matter how far they were, I acted as if they were able to overhear my conversations. Sometimes, I would perform foreignness. At other times, I would acquaint myself with other park-goers, and even pay serious attention towards what they were doing. For example, I would pretend that I was taking notes during a singing lesson taking place in a very visible spot of the park; In the gaze of an audience, I also enthusiastically joined a man who, every evening, practised his singing skills in the park, singing Pao Ma Liu Liu De Shan Shang, a popular song from Kangding in Sichuan; I would sometimes do my best to maintain long conversations with some people, discussing most mundane topics—Such ordinary discussions used to be part of my fieldwork routine even before I started being followed and watched. However, I felt that my engaging in conversations with others in the park, in the changed circumstances, was purposely directed for my audience rather than for serving the need of my research.

This acting itself to convey signs of my involvement in innocent activities before the audience, constituted an attempt to overcome difficulties in getting fully engaged in my usual due tasks for fieldwork; that is, jotting notes, taking pictures, and the like. Acting was then a way to be able to keep on working, and at the same time, an acknowledgment of surveillance. Obviously, my tentative role embracement was disrupted by my frequent, irrepressible glances at the guards and plain-clothes policemen, which could possibly be interpreted as expressions of discomfort or mere annoyance, in search of recognition or sympathies. Unsurprisingly, my every attempt to communicate, albeit non-verbally, with the men watching or following me failed to improve my discomfort as their own responses often revealed little of their intention towards me– It occurred approximately twice or three times that I engaged in verbal interactions with the bao’an. Although talking to them helped normalise the situation a bit and briefly reduced discomfort, I found these interactions a failure as I had to face overt concealment of intentions during my interlocution.

Concluding Remarks

My glances and occasional interactions, though scarcely verbal, with the guards indicated that while performing an innocent role, I was conscious of the fact that I was watched and followed. This means that I not only accepted the definition of the situation imposed by the authorities but also tried to take part in its making, reasserting my presence despite the constraints. Having said this, despite my efforts to keep on working under constraint, the way I conducted fieldwork underwent some changes as the situation evolved after the first interrogation. The number of my visits to the park was reduced during the second month in the field as I chose more carefully when to visit it and avoided the north-western corner on Sundays, loosing contact with one of my closest informants.

The significance of the situation is twofold. On the one hand, surveillance here, albeit as uncomfortable as it can be for any researcher, did not prevent my access to the field, at least not formally. As I mentioned earlier, no explicit interdiction was ever formulated neither by the policemen during interrogations nor by the security guards. On the other hand, such a situation redefined by the authorities left a certain kind of incertitude in terms of the boundaries of what I was still able to do or talk about as a fieldworker. Although there might be a risk of jumping in interpreting my micro-level observations to more general conclusions, the mode of control described above may be regarded as epitomising one of the ways in which the Chinese authoritarian power performs itself; using dissuasion rather than total repression and formal interdiction and as a result, leaving margins of incertitude to the boundaries of what is possible.

References

Farquhar, J. (2009) The Park Pass: Peopling and Civilizing a New Old Beijing. Public Culture, 21(3), pp. 551-576.

Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Anchor Books

Goffman, E. (1972) Encounters: Two Studies in the Sociology of Interaction. Allen Lane, The Pinguin Press

Ying, X. (2001) Dahe yimin shangfang de gushi. Beijing: Sanlian Shudian

About the Author

Lisa Richaud is a doctoral candidate of the F.R.S – FNRS at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (Free University of Brussels), Laboratoire d’Anthropologie des Mondes Contemporains. Her research project examines the social construction of a particular type of public space in urban China, namely public parks in the city of Beijing.

A Note on the Research

The fieldwork explained in this article took place from May to July 2012 in Xicheng and Dongcheng districts of Beijing, China. This was part of her doctoral research, which is expected to be completed in October 2015.

3 Comments