As foreign nationals are required to secure permission before commencing research activities in Rwanda, conducting fieldwork in the East African country has been a complicated matter for many researchers, especially those investigating politically sensitive topics such as the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. However, a host of researchers know little about the authorisation process or simply neglect to go through it. As Jessee (2012) points out, the failure to satisfy the requirements is attributed in part to a reluctance to invest time and money in seeking government permission or “lack of familiarity with Rwandan protocol”. Since Jessee delineated how to explore the process in 2012, it has changed quite considerably without detailed instructions available in the public domain. Having navigated the new procedure ourselves, we intend this written piece to provide up-to-date information based upon our findings, verified with the relevant government agencies in person and over the phone between October 2018 and April 2019.

Unfortunately for those residing outside Rwanda, it is virtually impossible to find the comprehensive information necessary to explore the authorisation process. Our observations point to a lack of coordination between the authorities involved in it. This can lead to confusions, misinformation or, in some cases, significant delays and thus necessitates up-to-date guidance on the new procedure, which was announced this year. Even though this bureaucratic hurdle may create an atmosphere of frustration, there is no justification for undertaking unauthorised research activities. Not securing permission or doing so by furnishing the authorities with false information about the details of proposed research compromises the integrity and legality of the data collected in the country and possibly leads to suspension of fieldwork. Accordingly, non-Rwandan researchers have both legal and ethical obligations to meet the requirements before commencing their fieldwork. As obtaining a research permit can take up weeks and months, this guidance clarifies the requirements in detail so as to help those considering Rwanda as a potential field site go through the process as efficiently as possible.

First and foremost, it is of paramount importance that one understands Rwanda’s political and historical contexts. Fieldwork tends to end up with discussions on the genocide, irrespective of the research topic. Although the physical destruction the genocide caused may no longer be visible, most people’s lives remain very much affected psychologically, socially and economically. For this reason, grasping a contextual understanding would help researchers of any discipline conduct fieldwork in a way that is ethically sound and socially responsible. Moreover, there is a belief amongst researchers that the Rwandan government creates a hostile environment for foreign nationals conducting fieldwork in the country. In discussing her experience in Rwanda between 2006 and 2007, Thomson (2013) illuminates the challenges that she faced whilst researching the genocide. Rwandan authorities were unwilling to let her interview alleged perpetrators of the genocide who had been incarcerated. Although this rather restrictive environment would not be conducive to any research, it was inevitable given that those responsible for the genocide and other human rights violations were still being prosecuted. An estimated two million people were put on trial between 2005 and 2012 (France 24, 2019), during which the East African country strived to prevent any external influence on the process of restorative justice. The East African country no longer has such a hostile environment. In fact, it has gradually made it easier to obtain a research permit over the past decade. The principal reason for the latest revision of the process is also to better respond to growing numbers of local universities, their post-graduate programmes and research projects conducted by national and international researchers in the country.

Since the authorisation process has been set out to protect Rwandan citizens and national interests, the rationale and methodology of research and its implications for knowledge production and Rwandan society should be clearly demonstrated. It is equally crucial to elaborate on how to ensure the safety of participants and of researchers themselves. Proposals lacking such details may result in re-submission or disapproval. The Rwandan government has the right to determine what is done within its sovereign territory, as does any national government. Therefore, research projects which appear to be unethical, poorly designed or potentially detrimental to the interests of the people and the country may be rejected.

The process entails four steps: screening, ethics review, permission, and registration. It does not discriminate against anyone on the basis of nationality, ethnicity, race, gender, religion, disability, political leanings, or other markers of identity. Rwandan researchers, too, are required to go through an ethics review if their projects involve human subjects. The main concern is, rather, whether the proposed research has the potential to benefit knowledge creation and, more importantly, Rwandan society. As research proposals are reviewed on their individual merit, the requirements may be subject to modification. The fact that the proposed research has already been approved by the review board of researchers’ home institutions has no bearing on the likelihood of approval by the Rwandan government. For sector-specific issues arising during or after the process, researchers are advised to consult with those who have previously conducted research of similar nature, organisations operating in the country, or relevant local authorities.

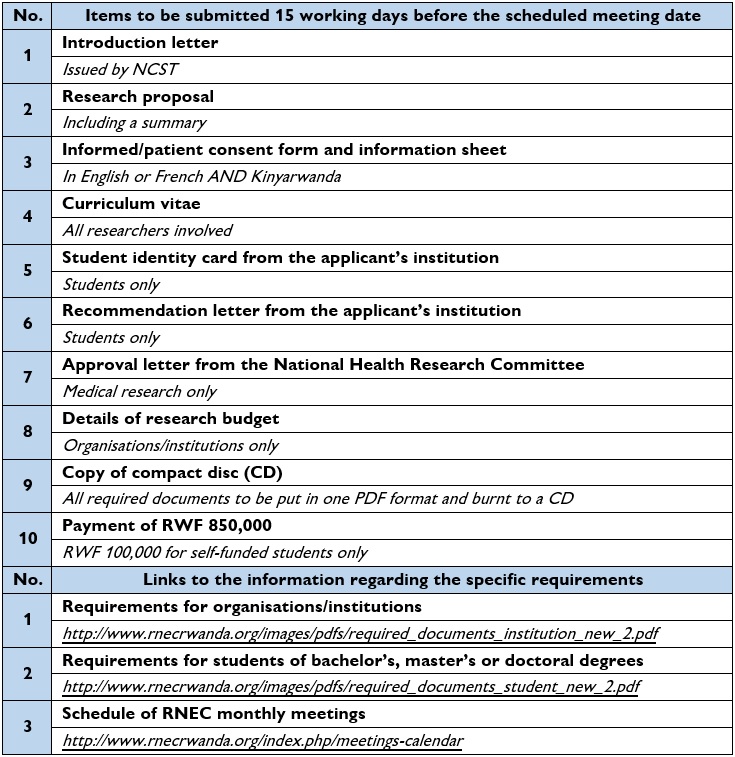

The specific requirements of each step are listed in Figures 4 and 5. Nevertheless, it is advisable to double check with the relevant authorities before submission in order to avoid disappointment. One major change made to the authorisation process is that the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) no longer has any involvement in it, but surprisingly many still believe that permission is granted by MINEDUC. The role of MINEDUC in issuing a research permit has been handed over to the National Council for Science and Technology (NCST), a regulatory entity created in response to growing numbers of post-graduate programmes and both local and foreign researchers doing fieldwork in Rwanda. In the initial step, NCST reviews the details and legitimacy of the proposed research. If human subjects are involved in it, researchers receive an introduction letter necessary to apply for an ethics review by the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (RNEC), which was established in 2008 to safeguard the rights of participants and protect researchers. The subsequent step may be waived for those whose research does not involve human subjects. During the second step, researchers make a 15-minute PowerPoint presentation during the monthly meeting of the RNEC held on the first or second Saturday of each month. Required documents must be submitted, preferably in person, at least 15 working days in advance. The presentation is followed by a Q&A session with the ethics panel consisting of eight committee members. It is worth noting that research projects dealing with politically sensitive subjects can be subject to more scrutiny. It takes roughly two weeks for written feedback to be given, possibly with some conditions attached. Once the conditions have been fulfilled, the proposed research is granted ethics clearance. In the third step, NCST produces a legal permit. The final – and rather formalistic – step is taken at the Directorate General of Immigration and Emigration. Foreign nationals are required to acquire an appropriate visa even if their fieldwork can be completed within the period allowed by a visitor’s visa. Last but not least, should it become necessary to renew a permit, both NCST and the RNEC must be informed of the reason for an extension.

The new procedure is unlikely to change for the time being, for it was announced in 2019. That said, we reiterate the importance of regularly ascertaining whether any amendment has been made. It has come to our attention that the authorisation process, which looks complex and overwhelming at first, discourages some researchers from choosing Rwanda as a field site. Our observations suggest, however, that securing permission is a relatively straightforward process even for those seeking to address sensitive topics, provided that the rationale, methodology, and implications of research are duly addressed with appropriate actions for risk mitigation taken. Furthermore, the process entails benefits for researchers themselves. It does not only enhance the ethical rigour of research, but also ensures adequate support for those who are unfamiliar with their field locations. For example, the requirement of local affiliation, which the Rwandan government considers as proof of the relevance and legitimacy of research, turns out to be instrumental in providing foreign nationals with a degree of protection and logistical assistance whilst in the field. So long as researchers elucidate the details of fieldwork, present thoughtful ethical considerations and submit all required documents on time and to the right place, obtaining a permit should not be as daunting a process as it may seem from afar.

References

France 24 (2019) Seeking justice: The long hunt for Rwanda’s killers. Retrieved from https://www.france24.com/en/20190402-seeking-justice-long-hunt-rwandas-killers.

Jessee, E. (2012) Conducting fieldwork in Rwanda. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d’études du développement, 33 (2): 266–274.

Thomson, S. (2013) Academic integrity and ethical responsibilities in post-genocide Rwanda: working with research ethics boards to prepare for fieldwork with ‘human subjects’. In S. Thomson, A. Ansoms, & J. Murison (Eds.), Emotional and ethical challenges for field research in Africa: the story behind the findings (pp. 139–154). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

About the Research

The written piece is based upon findings from the early stages of an ethnographic research project that centres on gender and education in post-genocide Rwanda and emphasises the importance of recognising the specificity of individual countries. The study is designed to explore the ways in which, and the reasons for which, girls’ education is used as a way of promoting gender equality, ascertain its effects on – and through – everyday lived experiences, and cast light on discrepancies between statistical evidence and narrative accounts. The blog post conveys useful information drawn from the authors’ first-hand experience of obtaining a research permit in preparation for their data collection activities. In doing so, the authors, as a foreign researcher and a Rwandan national, provide a uniquely balanced view of the authorisation process for those who consider or plan on conducting research in the East African country.

Interesting read, thank you. I happened to notice that Irembo has an online application form for a research permit. This hints that the process would have streamlined but of course, it is not a guarantee that other paperwork might need to be done. If the author or other readers of this blog have some recent experience, I’d be interested to hear. I am currently a resident of Rwanda and I’m drafting a plan for future academic research activities.

Thanks for your comment, I think there might be now such an application to IREMBO for research permit, I also need to check! but since you are here in Rwanda and making your plan for your research activities, consider making appointment with relevant people to avoid surprises (In case you have limited time and budget for your research)

With COVID -19 restriction measures in place, field activities such as conducting interviews might also be limited, seeking guidance mainly from Rwanda National Ethics Committee would precocious.