While conducting research in my home city in a neighbourhood that I was not that familiar with, I was simultaneously an insider and outsider in this neighbourhood. For insiders doing research in their home city, a more challenging issue is how the research could force the researcher to question him/herself, as the researcher is part of the subject of the research. This intimacy as insider may make the researcher suffer more emotionally than ordinary outsider, writes Yi Jin.

_______________________________________________

The difficulty of in-betweenness

Doing research in one’s home territory (either the home country or the home city) is not necessarily an exciting experience as described by Ite (1997). The issue of positionality, which has long been a critical concern to field researchers in geography (Cupples and Kindson, 2003; Rose, 1997), is more keenly felt for a “returning-home” researcher. A researcher may face some kind of antagonism between “insider” and “outsider” (Giwa, 2015; Rubin, 2012), but a “returning-home” researcher will inevitably bear two identities at once, or embodying a kind of “in-betweenness” (Rubin, 2012; Till, 2001; Zhao, 2017).

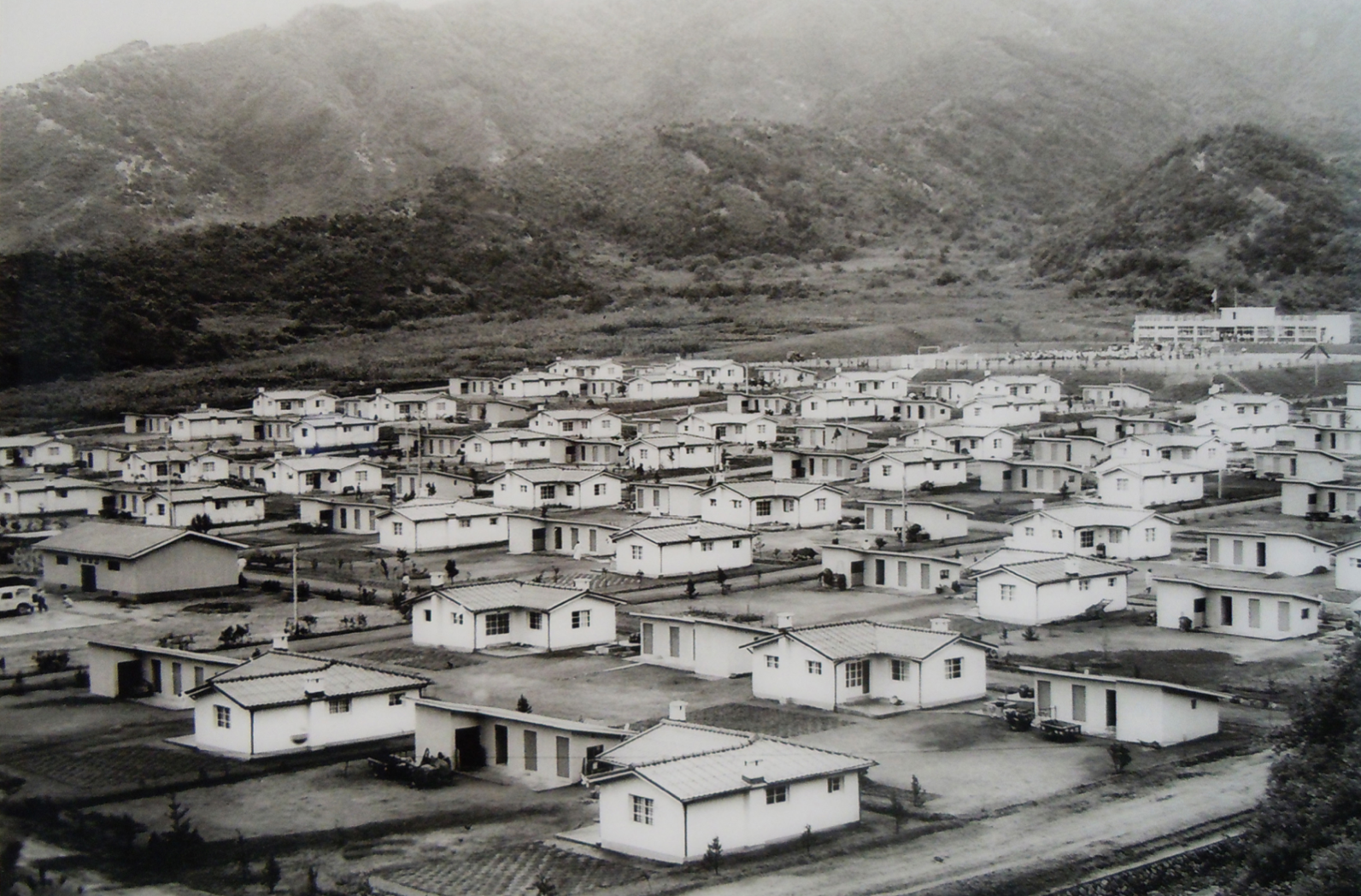

This situation is the one I found myself in. I conducted my PhD research on the topic of urban redevelopment and residents’ relocation in my home city, the city of Luzhou in Sichuan Province. But at first, I was not familiar with the neighbourhood I meant to work in, which was to be entirely redeveloped. This neighbourhood was constituted mainly by three large-scale work units (danwei in Chinese), encompassing the work plants of three large factories and workers’ residential buildings. It was relatively isolated from the city centre, and residents, as the (former) colleagues of the factories, were familiar with each other.

I was simultaneously an insider and outsider in this neighbourhood. On the one hand, I was an insider. My identity as a native of Luzhou helped me considerably when I was trying to recruit interviewees, either local officials or residents, by navigating within my personal network. I could establish contact with some residents within this neighbourhood through my parents, teachers, former classmates and other friends. Those who knew me in person would be clear about my background (as a local person) and my intention (working on my PhD thesis) and it would not be difficult to interview them without too much effort spent on clarification. Through snow-ball sampling, I managed to establish contact with more residents for interview.

But on the other hand, I was more an outsider. The identity of “outsider” itself is dual, an outsider in their neighbourhood and an outsider in the country (being affiliated to the LSE, a foreign university based in the UK). Those residents who did not know me, especially those I came across, found it difficult to fully trust me and to understand the purpose of my research as an outsider in their neighbourhood, although they agreed to be interviewed (for a similar case, see Hasnain, 2014). Moreover, even when I told them I was just a PhD student, some residents still did not believe me. A common suspicion was that I might be a journalist. But as the press in China is under strict censorship of the Communist Party, the residents believed that a journalist would hardly be able to make their voices heard and therefore chatting with me would be pointless. In one case, a respondent even tried to persuade me to stop interviewing because picking up rubbish for recycling might earn me more money than this useless work would, as there were many rag-pickers in their neighbourhood which was under demolition. To some degree, I was irritated by his words at first, but soon realised this reaction revealed how desperate these residents were in the face of the inevitable demolition of their dwellings.

However, being misunderstood as a journalist was not all negative. For example, during the preliminary fieldwork, just before my arrival in the neighbourhood on the morning of 14 September 2015, an enforced demolition work was in progress (see Figure 1). I met a resident there who still seemed taken aback after having witnessed the mighty use of the state power in the demolition process. I tried to ask this woman some questions. Without any detailed knowledge of my purpose there, this woman invited me into her house and called in some of her neighbours to chat with me. She misunderstood me to be a journalist. After I clarified my identity, this chat became an ad hoc group interview. She and her neighbours lived as “nail-households”, having held out against compulsory resettlement. Being awoken by the enforced demolition, they had much to complain about. This group interview lasted for more than five hours. By chance, one of the respondents in this group said that he had often seen me in this neighbourhood with my camera, thus endorsing my statement that the purpose of the interview was academic research. I noted down the contact details of some of these residents and held a second interview with them to update what I knew of their experiences.

In addition to journalists, some of the local residents regarded me as the secretary of a high official, or as a member of an inspection group (xunshizu) who had been sent incognito to collect public information that might help alleviate their hardships; thus they were happy to be interviewed by me. In one case, hearing that I promised anonymity in using the information collected in the interviews, a respondent even asked if I could include his real name to better publicise his case.

The suspicion that I was a member of the inspection group casts a somewhat bitter light on a very interesting story that I explain at length below. Sending out inspection groups has been an important measure in the Communist Party’s nationwide anti-corruption movement since 2012 (cf. Yeo, 2015). The primary task of inspection groups is to collect information in relation to corruption or misconduct on the part of the leading local party cadres. According to one respondent who suspected me to be a member of an inspection group, he happened to know that the provincial party branch had sent an inspection group to Luzhou early in 2015. This group published its contact address and said that any report was welcome. The residents suffering home ownership dispute saw this as a chance to get their persistent problem solved. Therefore, they sent some representatives to meet the inspection group. To their disappointment, the reception staff turned them down and recommended them to compromise, take the government’s compensation package. Such a lukewarm response irritated the residents. They heard that there were two inspection groups: the real one and a “counterfeit” organised by the municipal party committee to baffle people. They believed that the group they had met was beyond question the “fake” one.

It is possible that these residents did meet a “counterfeit” group, which may hint at a sophisticated mode of governance. But it is also possible that the inspection group they met was “authentic”. However, on the surface, what the group wanted to collect was clues suggesting the misconduct or corruption of local cadres, putting these residents’ specific appeal in relation to their housing outside its terms of reference. It is therefore understandable that the inspection group did not take serious account of the residents’ appeal. But the residents were inclined to accept the first possibility and believe that they had met the “counterfeit”. The “authentic” inspection group, wherever it was, could still, they believed, lend a hand. It was not so much that they suspected that I had concealed my identity as that they hoped I had done so. They wished me to be the kind of person who could help them (also see Liu, 2000: 19; Svensson, 2006: 268-270), indicating how they were still relying on the benign state. Although I had very often clarified that I was simply a doctoral student and I could do hardly anything to produce an instant effect on their situation, they still asked me to “make them heard”.

My identity as a kind of outsider of this country brought me up against more barriers. In an extreme case, a respondent suspected that I was a spy. In another case, a potential respondent turned down my request for an interview, although I was introduced to him by his colleague, who knew me personally; he still believed that it was inappropriate to expose the misconduct of local officials to people with links abroad. He insisted that he should avoid “washing your dirty linen in public” (jiachou buke waiyang). Others who accepted my interview were still not quite confident about whether it was “appropriate” to talk about these issues with me; hence they demanded me to write impersonally and maintain anonymity. In addition to a general sense of obedience under the authoritarian regime, the residents’ cautiousness also had something to do with the background of the enterprise they served in, which was established during the Third Front Construction (see Naughton, 1988). As some products of these factories had been put into military use, they had long been disciplined to take care of any possibility that would leak the secret. In my interviews, some residents even emphasised that what he or she was talking about was no longer confidential, so he or she could share this information with me.

Using camera: unexpected disturbance

During my fieldwork, I paid frequent visits to this neighbourhood to conduct interview or just for observation, because as an outsider, I need to get familiar with this neighbourhood and be noticed by local residents. Sometimes, I carried my SLR camera to take photos of the buildings in and the landscape of this neighbourhood (see Figure 2). I used this strategy internationally as I could let myself be seen by local residents. After some visits, I calculated, local residents would notice me and be curious who I was and what I was doing. Then, I could chat with them and find a chance to ask for an interview.

But much to my surprise, my strategy to encounter more potential interviewees by carrying my camera generated a kind of anxiety among other residents. In the course of my fieldwork, I saw others taking photos, especially when demolition was taking place, or in the workshops as a record of local history. A local resident, whom I had a successful interview with later, questioned the purpose of my photography. After hearing my explanation, he did not ask me to stop but explained that the Sub-district Office had recently sent someone to take photos of their buildings, which the residents interpreted as a signal that the Sub-district Office would accelerate the pace of expropriation and had complained about to the Sub-district Office. I realised it was highly likely that I was the person being complained about, because at that period, I always wandered around these neighbourhoods and took photos, but did not encounter anybody else doing the same as me. They had misunderstood what I was doing, but nobody had come to stop me, indicating how apprehensive these residents were and how tense was the relationship between the local state and local residents.

Overcoming the difficulty as an ‘outsider’

I tried in several ways to reduce residents’ suspicion and overcome the difficulty as an “outsider”. It was not difficult to tackle extreme cases, such as the suspicion that I was a spy. I merely asked the resident to think of any information she possessed that could endanger national security; she then realised that she had overreacted. In other cases, it was still my identity as an “insider” that helped me. First, I could speak both standard Mandarin (Putonghua) and with a local dialect. I used the Luzhou dialect with local residents to convince them that I was native to the place. With migrants of the Third-Front Construction (see Jin and Zhao, forthcoming) who still spoke standard Mandarin or some other accents of Northern China, I tried to reduce the distance between us by using a mixture of standard Mandarin and a Luzhou dialect. When I mentioned that I had studied in Beijing for seven years, a migrant born in Beijing even called me a “person from the hometown” (jiaxiang ren).

Second, I showed them my LSE student ID card, but this did not help much, since only a few of my interviewees could understand English. Those who could did not know the LSE and its academic reputation. I then presented my previous student ID card from Peking University, which I had obtained when I was a Master’s student there. Such an identity helped me gain more trust from the residents, since Peking University is the top university in China.

Third, in my interviews, so long as I did not leak anyone’s privacy, I was able to refer to information I had obtained during my fieldwork when interviewing some residents. The information included the details of the compensation scheme, and the state policies on redevelopment. Hearing these details, sometimes surprised the residents, who were convinced by the amount I seemed to know about what was happening in their neighbourhood and were more willing to give their own opinions.

Reflections

Reflecting upon my fieldwork in my home city, the in-betweenness as an insider/outsider definitely enabled my research more than constraining it. For an “overlooked city” (see Jin and Zhao, forthcoming), of which precedent work and the research network based on it are scarce, insiders’ personal knowledge of the city and personal network in the city are highly helpful. As illustrated by my own experience, comparing to these advantages, I would argue the challenges facing a researcher as an outsider are not quite difficult to overcome. For insiders doing research in their home city, a more challenging issue is how the research could force the researcher to question him/herself, as the researcher is part of the subject of the research, be it the city or a group of residents in the city (see for example Zhao, 2017). This intimacy as insider may make the researcher suffer more emotionally than ordinary outsider.

References

Cupples, Julie and Sara Kindon (2003). “Far from being ‘home alone’: the dynamics of accompanied fieldwork.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 24(2): 11–28.

Ite, Uwem (1997). “Home, abroad, home: the challenges of postgraduate fieldwork ‘at home’”. In Elsbeth Robson and Katie Willis (eds.) Postgraduate fieldwork in developing areas: a rough guide. London: DARG monograph 9: 75–84.

Giwa, Aisha (2015). “Insider/outsider issues for development researchers from the Global South.” Geography Compass 9(6): 316–326.

Hasnain, Saher (2014). “Fieldwork at Home: Assumptions, Anxieties and Fear”. LSE field research blog. Available at https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/fieldresearch/2014/05/28/fieldwork-at-home-assumptions-anxieties-and-fear/

Jin, Yi and Zhao, Yimin (forthcoming). “Sanxian: re/un-thinking Chinese urban hierarchy with a medium-sized city.” In Hanna A. Ruszczyk, Erwin Nugraha and Isolde de Villiers (eds.). Overlooked Cities: Power, Politics, and Knowledge Beyond the Global South. London: Routledge.

Liu, Xin (2000). In One’s Own Shadow: An Ethnographic Account of the Condition of Post-reform Rural China. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Naughton, Barry (1988). The Third Front: Defence Industrialization in the Chinese Interior. The China Quarterly 115: 351-386.

Rose, Gillian (1997). “Situating knowledges: positionality, reflexivities and other tactics.” Progress in Human Geography 21(3): 305–320.

Rubin, Margot (2012). “‘Insiders’ versus ‘outsiders’: what difference does it really make?” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 33(3): 303-307.

Svenssom, Marina (2006). “Ethnical Dillemmas: Balancing Distance with Involvement.” In Maria Heimer and Stig Thøgersen (eds.). Doing Fieldwork in China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press: 262-280.

Till, Karen E. (2001) “Returning home and to the field.” Geographical Review 91(1-2): 46–56.

Yeo, Yukyung (2015). “Complementing the local discipline inspection commissions of the CCP: empowerment of the central inspection groups”. Journal of Contemporary China 25(97): 59-74.

Zhao, Yawei (2017). “Doing fieldwork the Chinese way: a returning researcher’s insider/outsider status in her home town.” Area 49(2): 185-191.

About the Research

Yi Jin’s doctoral research explores the changing mode of urban governance in China that bears the characteristics of managerialism and entrepreneurialism simultaneously by investigating the national project of shantytown redevelopment and its implementation in a city in Sichuan Province, Southwest China.

For citation: Jin, Y. (2020) In-betweenness: Doing research back home. LSE Field Research Method Lab (17 September 2020) Blog entry. URL: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/fieldresearch/2020/09/17/doing-research-back-home/

1 Comments