Very few people realise that undertaking research is often an emotional experience. Most often, the researcher is forced to confront and explore their own subjectivity and emotions stimulated by encounters in the field. Reflexivity, in this regard, enables researchers to not only self-critique their frame of reference but also address ethical issues that emerge in field work, writes Navjotpal Kaur.

_______________________________________________

“…then he pointed a gun to my face and threatened to rape me.” Nothing could have prepared me for such a dramatic, intense switch from a casual conversation to a morbid one. I was interviewing young men in Punjab for my doctoral research on caste, masculinity, and the body when I came across a homosexual youth belonging to an ‘upper-caste.’ I was excited at the prospect of including an upper-caste homosexual man, whom we will call Jogi from here on forward, in my sample and was looking forward to learning about his experience of caste-embodiment in Punjab, India – all my other interviewees had been unequivocally heterosexual, a fact which I hadn’t really paid attention to until Jogi contacted me. I started the conversation with some icebreakers from my interview guide as we sat down on a park bench… A slender and seemingly timid young man, Jogi was eager to learn more about my research and asked me several questions before answering mine.

When I started my fieldwork, I was not actively seeking, or expecting, to interview homosexual Punjabi men. As an ‘upper-caste’ female who had spent most of her life in urban Punjab or Canada and mostly within academic environments, my positionality unknowingly affected my research framework which, as I realized later, was largely heteronormative. As I came from the perspective of a person with relatively different life-experiences and worldview, I had little degree of commonality with Jogi unlike my other participants. When Jogi narrated to me the incidence where his life was threatened because of his sexual orientation, I was overwhelmed with a feeling of utter helplessness and concern. My initial thoughts focused on my inability, as the researcher, to remedy things as I became acutely aware of my position as a privileged outsider in Jogi’s world. I immediately contrasted him with other men I had interviewed before him and realized how power and privilege associated with the upper-caste was stripped from him and his masculinity pushed to a subordinated, othered, and marginalized position because of his sexual orientation. To effectively empathize with Jogi, I reflexively tried to find some commonalities between us. For instance, by discussing the dominant hetero-patriarchal ideology of the caste we both belonged to and our experiences as people who frequently find themselves in a marginalized position – on account of gender (me, as a woman) and sexuality (him, as a homosexual man). Somewhere in the process of actively trying to find relatedness between our lives, the interview transcended from being a typical question-answer format into a deeper, more personal conversation. As the researcher, it was a rewarding exercise as it made me understand the traumatic experiences in Jogi’s life and their aftermath more comprehensively.

When done carefully, in the research process, acknowledging and reflecting on emotions can open cathartic avenues for the researcher as well as the participant. Emotions enrich the research by shifting the data collection process beyond the realm of an objective and perfunctory exercise and by providing a more nuanced and compassionate understanding of what is said and observed. My overwhelming feeling of helplessness was somewhat mitigated when Jogi conveyed to me, after I asked if I could do something to help, that talking about his experiences with me had been therapeutic for him and that it was the first time somebody had listened to him without being judgmental. While this knowledge brought me a little relief, the emotion and concern I felt in the interview did not completely disappear. I had to play the role of a confidante in addition to being a researcher – the information Jogi shared with me was highly sensitive and I was very cautious of any accidental lapse in confidentiality. It is with great care and responsibility that I share the incidence in this space because it helps highlight the importance of reflexively considering and negotiating emotionality in intense field encounters for the researcher.

In this blog post, I have attempted to unpack the nuances of researcher positionality and preparedness by focusing on acknowledgement of emotion and importance of reflexive practices. Very few people realize that undertaking research is often an emotional experience. In empirical qualitative studies, there is always a ‘risk’ for the researcher to become absorbed in personal worlds of those being researched. Most often the researcher is forced, or I would say has the opportunity, to confront and explore their own subjectivity and emotions stimulated by encounters in the field. Many researchers have time and again chronicled difficult experiences in the field, yet reflexivity and emotional vulnerability remain understudied in research methodology in all stages from design to execution. Reflexivity enables researchers to self-critique their frame of reference and address ethical issues that emerge in field work.

A key lesson I learned from the encounter with Jogi is that it is vital to realize the significance of sharing of emotional experiences for both the researcher and the participant. Acknowledging and reflecting on the emotions evoked in me helped me expand the base of my expectations from the fieldwork. Researcher’s method of engaging with the data (collection and analysis) and resulting emotional reactions not only impact researcher’s positionality but become an important source of reflexivity in negotiating the portrayal of extraordinary incidents in research. For the researcher, being aware of one’s subjectivity—and navigating research relationships with participants accordingly—is particularly imperative when working with vulnerable and marginalized populations.

Note:

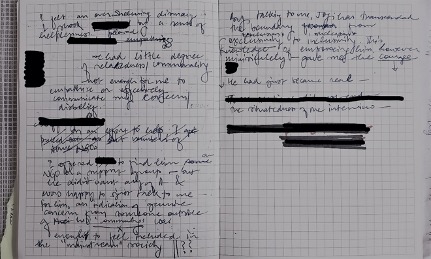

- The main photograph is by the author, taken in a small town near Jalandhar in October 2020.

For citation: Kaur, N. (2020). Field realities in the global South: Acknowledging emotion and the importance of reflexivity. Field Research Methods Lab at LSE (6 January). Blog entry. URL: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/fieldresearch/2021/1/6/field-realities-in-the-global-south-acknowledging-emotion-and-the-importance-of-reflexivity/