Taking an ethnographic road to disaster-affected communities makes us grow deeply aware of seething worldly inequalities that disasters bring forth. At the same time, it makes us compassionate towards the world outside. It is imperative we reserve a piece of that compassion for our own selves too, writes Mausumi Chetia.

_______________________________________________

On a summer night eleven monsoons ago, sleep evaded me. Outside, the winds were growing stronger by the hour and the skies refused to stop pouring. My sleepless thoughts held the image of a family and an incessantly shaking, frail, stilt-house (chang-ghar), built over a flowing drain.

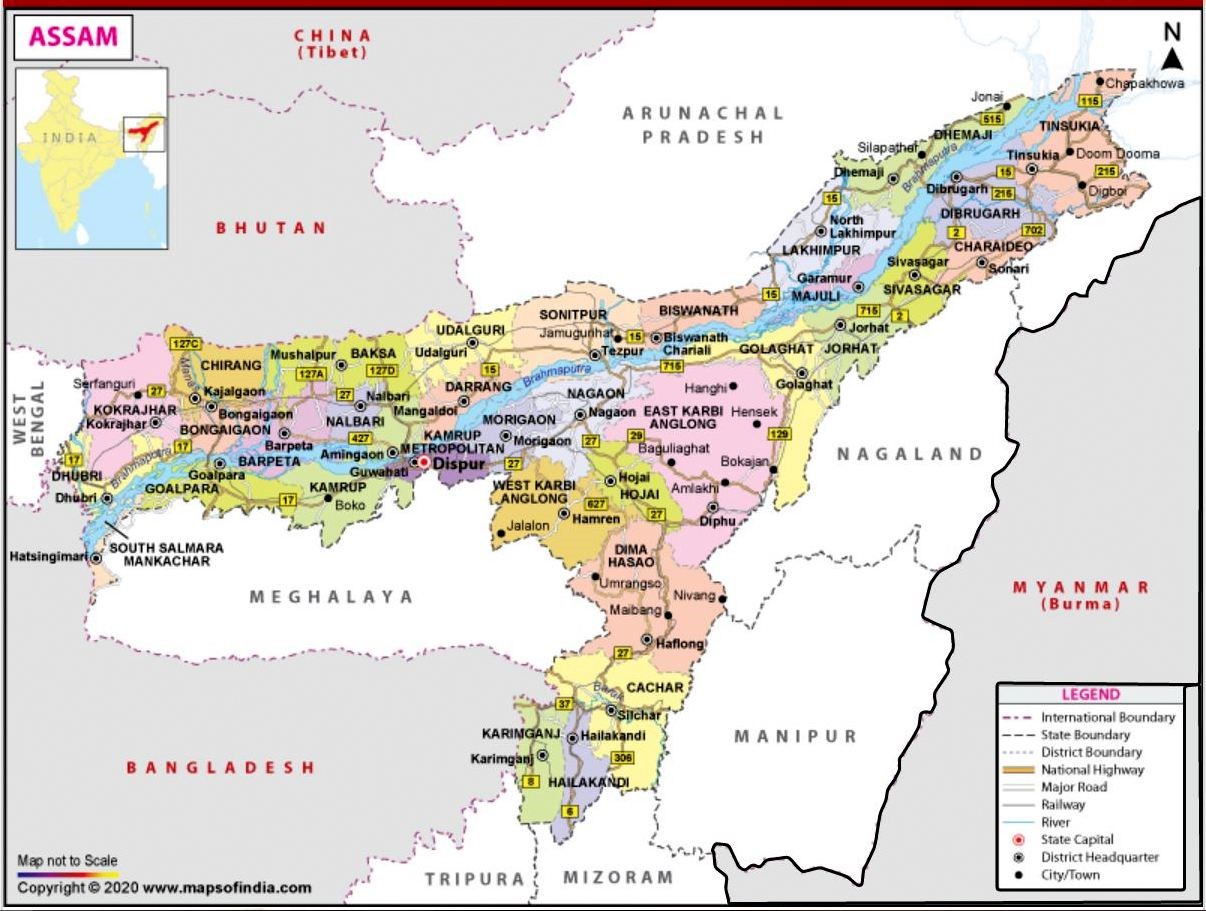

I was in Majuli, an island on the Brahmaputra river of Assam; one of the eight states of North-eastern region of India and my home state. I was collecting data for my master’s dissertation around the time the monsoons began bringing the annual floods to our state. A few days later, my then research supervisor pulled me out of the fieldsite. With a calm but commanding voice, she asked me to return to ‘safety’ at the earliest. With partially collected data, mixed emotions and a river that was continuously expanding (due to massive erosion of its banks) – I left Majuli for my home’s ‘safety’.

Fast forward to fieldwork for my current research in Assam in 2019. I was faced, once again with the ethical dilemma of applying a methodological approach vs prioritizing a researcher’s self-care. The very puzzles I had left behind midway in Majuli, a decade ago. Because research is a deeply political process but it is a humanizing journey too (Kikon, 2019); both being mutually inclusive.

The half-written story of a monsoon auto-ride: taking a submerged road in July

My fieldwork in June 2019 took me to one of Assam’s severely flood prone districts. The geographical location was chosen based on longstanding professional relationships and empirical familiarity of that region.

Figure 1: Map of Assam, Inida

A local humanitarian organisation aided me in accessing the research population. I rented an accommodation in the district town, about 45 kilometres away from the actual site of study. My research populations lived about 15 to 25 kilometres away from a national highway, in a rehabilitated government land and along the banks of a river respectively.

The initial fieldwork days were about establishing access and meeting key contacts. The weather was mostly cloudy with occasional showers. One day looked particularly promising, with the sun high up on a clear blue morning sky. Predictably, the sky got dark in no time. Despite warnings of rising water levels, our auto-rickshaw driver decided to risk continuing the trip. Then began the drizzling.

I could see a blurring silver line across the trees. It was the water. My heart skipped a beat, remembering the last time I was in a heavily flooded river in a steamer boat, almost two monsoons past. Some thatched houses appeared inundated already. Buffaloes and cows were clutching tiny islands that had formed in the paddy fields, which in turn resembled huge lakes on either side of the road.

Gradually, it felt like we were surrounded by a sea. There came a point where the road ahead looked completely submerged. Our autorickshaw had to come to a halt.

A few vehicles had stopped ahead of us. The rain continued pouring. There was chaos and confusion. People needed to cross the submerged part of the road to reach their homes. But the prospect of crossing the waist-deep water with their luggage, infants and children delayed their decision. Three of my fellow passengers shared that they were indeed afraid of the water. Nonetheless, they must cross it on foot. Devoid of alternatives, two women and a teenaged boy started marching ahead. Many, like them, were from villages as farther ahead as 15 kilometres.

An ethical-methodological dilemma

I continued standing there next to our auto-rickshaw, almost in a stupor. A billion thoughts crossed my mind. And here was my dilemma. By design, understanding the ‘everydayness’ of the research population was at the heart of my research methodology. By that virtue, even the present situation of crossing a flooded area – should have theoretically been something I had prepared for. However, faced with the disaster first-hand, I was anything but prepared to experience the ‘lived experiences’ of my research population. I found myself arguing whether loyalty to my research methodology was more crucial than personal safety; or, more importantly, being an empathetic researcher and registering the real difficulties faced by the research population, in hosting me in their flooded homes.

The first thing that was stopping me from stepping into the waters was not the fear of the water itself. We were witnessing people crossing the submerged road. And in all fairness, it was not an ‘alarming flood situation’ by any measure, while perhaps only moving towards that. But my concern was one of return. My rapport with these families had not matured adequately to a point that I could stay unannounced in my interviewee’s home. At the same time, if the rains continued (that was most likely), it would be risky to return. The families were already struggling with minimal living spaces. Basic amenities like food, drinking water, public transport access, markets, hospitals etc was already limited and at far off distances. With rising waters, it would be inappropriate to obligate them to accommodate an additional person.

I was tiptoeing ahead absent-mindedly with all these thoughts in my head, when my auto-rickshaw driver called out, asking me to return to the vehicle. Along with a few passengers, he was planning to return to the main highway. He insisted that I must too, as I looked like an ‘outsider’ and I wouldn’t be able to cross the road, like the ‘locals’. With a sense of self-betrayal, I shut my umbrella and got back to the vehicle. The next morning, we were informed that the entire road till the bank of the river (located at least 15 kms from where we had returned) had been submerged. Even steamer services to Majuli were shut indefinitely. I realised my return to meet the families would have to wait; let alone shadowing them in their quotidian lives. This reflected my limited role as an ethnographic researcher – to study the research population during disasters that very much defined the everydayness of their lives.

The ethnographic project is, in itself, embedded within power relations between the researcher and the researched (Behar, 1993: 31 cited in Prasad, 1998). Empirically speaking, the research population and I share our homeland (of Assam), culture and language, both literally and figuratively, to a considerable extent. Yet we are anything but parallel in the legitimacies of our respective lives. To begin with, for instance, my family or I have never encountered a disaster first-hand; albeit the empathy and anguish lived through visual media’s decades-long coverage of disasters in Assam. Concurrently, in my research, it is I who determine the design, selection of site, population for study and methodology. This essentially puts me in a position of power and privilege over the research population I study – who in contrast, had no choice in choosing my research through which to share their everyday lives.

Given this inequality, the power (of the researcher) could end up being wielded against the best interests of the researched in ethnographic studies during or post disasters. The delicate balance between prioritising the research methodology and prioritising the research population then becomes crucial for us as disaster researchers. The power divide and our mandate to negotiate these nuances becomes much more apparent during our fieldwork.

In my experience, it is crucial to remain empathetic and put the interests of the research population facing disasters before our own research methodology. Being critically reflexive (Foley and Valenzuela, 2005) is a useful exercise during long-term fieldwork with disaster-affected communities. Engaging in other aspects of fieldwork, for example, transcribing the initial interactions and detailing of fieldnotes, making contacts with local experts, etc. could be alternative choices to make use of the time in the event of field exigencies.

Growing together with our research: prioritising researcher’s self-care

Over a year has passed since the field experience elaborated above. Since returning to safety that day, I continue to keep wondering if the decision was methodologically ethical. My choice that morning reflects the power imbalance between the researcher and the researched very clearly. I call it power imbalance because I had the choice to not move ahead to meet the research population. Whereas they themselves had no choice to leave their flooded home and return on a sunnier, drier day. That is their life. These families continue living in similar conditions of high risk and vulnerability even today.

I made my choice balancing the palpable risks of entering a flooded area and as an ostensibly empathetic researcher. That being said, it was also because, I prioritised safety of the self. Many of our decisions as disaster researchers get shaped by our relationship of accountability to our host organisations (if any) and towards our own families and loved ones. Ensuring our own safety is one such challenging decision.

The timetables we initially prepare for fieldwork will most likely require adjustments as we progress. Besides field-related dynamics, external environment is an ever-present fluid factor. Disruptions in the external environment at personal, social, or political levels are beyond our control, with many unanticipated surprises. They may or may not have direct implications for our research population. Nonetheless, they might impact us – as humans, at an emotional level and indirectly leave an impact on our research. The disruptions may percolate into our research subjects – the way we perceive issues at ground level, collect relevant information and make meanings from that information.

From the dilemmas of my ethnographic fieldwork, I learnt to appreciate that our research is as much about us as human beings/researchers as they are about understanding research populations. As I examine their lives and they examine mine, we grow together. After all, ours is a social and not a controlled laboratory situation. What I seek to reiterate here, is this: many aspects of fieldwork are beyond our control. What is in our capacity, however, is to take care of our own research, the research population we engage with and our own selves i.e. self-care of the social, individual human being within the researcher.

By self-care, I refer to not just the physical and mental/emotional health safety. Beyond such well-defined medical aspects of health, I emphasize on being self-empathetic throughout the period of research, while referring to a researcher’s self-care. This is especially true if we engage with disaster-affected populations over long periods. Taking care of ourselves by rejuvenating the social being in us in any manner possible – through appreciation of family, forging/retaining meaningful friendships and interpersonal relationships at work, taking brief breaks from fieldwork (if time affords) – even if that means staying back at one’s base location or attending a play, is crucial to this kind of self-care.

Having and practising contingency plans for safety prior to the fieldwork and regular communication with supervisory teams and our support system is a must for disaster ethnographic researchers. That said, a researcher’s self-care must be held dearly by none other than the researcher themselves.

Traversing the ethnographic road to meet disaster-affected populations

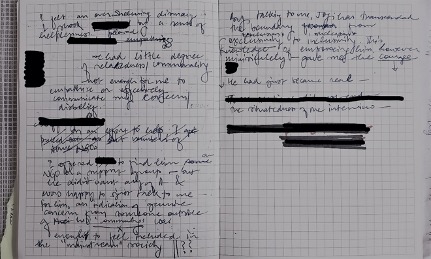

Upon my return from the flooded area, I found that colleagues at my host organisation were worried about me, as were my friends and family. I am glad I retraced my steps, albeit guiltily. In hindsight, I question if I should have changed my methodology considerably for smoother sailing. Or perhaps conducted fieldwork in areas with minimal probability for a disaster. In that case, how true will I remain to my research question and how ethical will that be? My original fieldnote from that day reads,

… this sight (of the flooded paddy fields all around me) is making me question, whether my original study population is even living in the same place where I’d met them or, have they already had to move, to avoid the rising river? What then does it reflect about the (mobile) lives that these (displaced?) families lead and to the credibility of the gaze I want/need to have for this research? (‘Reflections’ – Fieldnotes of a missed interview, 10th July 2019)

Such reflexivity helped me reshape aspects of my fieldwork’s methodology in tune with the dynamic external environment. Physical safety and mental health of aid workers are integral to policies and part of everyday conversations within the world of humanitarian aid. While discussing reflexivity in her autoethnography with disaster-affected communities of Aceh, Indonesia, Rosaria Indah (2018) shares that secondary traumatic stress (STS) could be one of the long-lasting impacts on disaster ethnographers. Thus, this conversation deserves to pick pace within the academic community too, especially for researchers engaging in long-term humanitarian contexts.

Informed by our empirical observations and academic training, we make a choice to live the everyday worlds of our research population, with optimally plausible authenticity. But doing ethnographic fieldwork during/post-disasters could be deeply taxing, as it is an intimate experience. Being critically reflexive during such times often leads us to the self and to the mosaic of identities and relationships, that we as researchers have within and beyond our own research. From my monsoon fieldwork in Assam last year, I learnt that while being empathetic to the research population, we also need to acknowledge, nurture and be ethical towards the person within the researcher. It is a deeply challenging act to balance, but one that is rewarding in the long run. When the self is taken care of, the researcher naturally thrives and so does the research.

Taking an ethnographic road to disaster-affected communities makes us grow deeply aware of seething worldly inequalities that disasters bring forth. At the same time, it makes us compassionate towards the world outside. It is imperative we reserve a piece of that compassion for our own selves too.

References

Foley, S. and Valenzuela, A. (2005) Critical ethnography: the politics of collaboration. In: N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, eds. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 217–234.

Indah, R. (2018) Probing problems: Dilemmas of conducting an ethnographic study in a disaster-affected area. International journal of disaster risk reduction 31, pp.799-805.

Kikon, D. (2019) On methodology: research and fieldwork in Northeast India. The Highlander 1(1), pp. 37–40

Prasad, P. (1998) When the Ethnographic Subject Speaks Back: Reviewing Ruth Behar’s. Translated Woman. Journal of Management Inquiry 7(1), pp. 31-36.

About the research

The author’s doctoral research is a part of the Vital Cities and Citizens programme of the EUR. Through her research, she examines the quotidian lives of families that face protracted displacement due to riverbank erosion and associated factors and their idea(s) of home, in Assam; through the lens of human security. Fieldwork of fourteen+ months was conducted through two phases, since December 2018. This piece originates from fieldnotes of a section of her ethnographic fieldwork, that was carried through the annual period of monsoon and consequential second wave of floods in the state; in June and July 2019.

As of July 2020, the floods are back to at least 25 districts of Assam, affecting over 1.5 million people, including the researcher’s referred fieldwork site. This continues amidst additional local disasters, while witnessing rise in Covid-19 cases in Assam, in the northeast of India.

For citation: Chetia, M. (2020) Traversing the ethnographic route to meet disaster-affected populations: Dilemmas of a monsoon fieldwork in Assam, India. LSE Field Research Method Lab (13 July 2020) Blog entry. URL: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/fieldresearch/2020/07/13/traversing-the-ethnographic-route/