Significant progress has been achieved since the Greek economy suffered one of the deepest and longest recessions of any advanced economy to date. Recently, the economy has proved resilient to the COVID-19 shock and new geopolitical risks. Yet, a number of challenges remain and Greece lags behind peer countries in various domains critical for long-term growth. The production structure is largely unchanged and domestic output lacks sufficient knowledge-intensive characteristics. Although the Greek innovation ecosystem has made progress in recent years, there are still weaknesses that prevent it from becoming the leading factor in the transformation process of the Greek economy, and skills gaps concerns persist. Substantial increase in potential growth is only possible through enhancing capabilities, raising the productivity of existing resources and engaging in innovation.

Most EU Member States, including Greece, have responded to the challenges posed by different drivers of skills demand by seeking to increase skills supply, notably through raising educational attainment. This is in line with projections of future skills demand shifting towards more highly skilled economic activities, as around half of all job openings over the next decade are expected to require a high level of qualification. However, while levels of educational attainment in Greece have increased, there are concerns that the education and training system is not sufficiently aligned with labour market needs.

In fact, university education is frequently criticised for not conferring upon its graduates the cutting-edge skills that the labour market needs. In other words, one of the major problems facing the Greek labour market is the relatively large share of low-skilled workers. Indeed, Greece had one of the lowest overall scores in the European Skills Index (ESI) survey of 2022, only marginally improving its performance relative to 2020. This low ranking is attributed to low scores in each of the three ESI pillars, pointing to a weak skills system in Greece on multiple fronts.

The low skills level of the Greek economy means that employers are unable to fill vacant positions because of skills gaps or shortages (lack of employees with suitable skills or qualifications), making mismatch between the supply of and demand for skills a significant impediment to potential growth. An efficient labour market needs to match workers of heterogeneous skills endowments across jobs of heterogeneous skills requirements. An efficient allocation of workers across tasks is particularly important when the aggregate skills supply is relatively limited, as is the case for Greece.

Data from PIAAC suggest that Greece suffers from a high level of mismatch between the skills workers possess and those demanded of their jobs. Around 28% of workers are more proficient in literacy than their job requires (overskilled), the largest proportion across all participating countries and much higher than the OECD average of 10.8%. Moreover, almost four out of ten workers in Greece are either over- or underqualified for the work they are doing. As for field-of-study mismatch, which measures the extent to which workers, typically graduates, are employed in an occupation unrelated to their principal field of study, 41.4% of workers are employed in a different field than the one in which they earned their highest educational qualification.

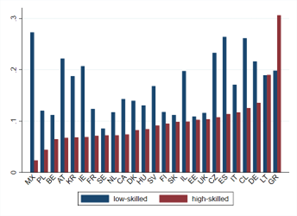

Persistent skills gaps and mismatches come at economic and social costs, while skills shortages can negatively affect labour productivity and hamper the ability to innovate and adopt technological advances. Figure 1 shows that Greece has by far the highest professional overskill mismatch (i.e. those working in highly skilled jobs are more proficient in literacy than their job requires) compared with all other countries in the sample. Overskilled workers tend to underuse their skills, resulting in a waste of human capital.

Moreover, splitting aggregate productivity in each sector into a within-firm component and an allocative efficiency component as in Adalet McGowan and Andrews (2015), reveals that overskill mismatch plays an important role for productivity, and overskilling in professional occupations, where Greece scores especially badly, is a major drag.

Turning now to another important area for action, namely management practices as a driver to enhance productivity, we see that not only does Greece score last among other OECD and EU countries in the World Management Survey (WMS) sample but also that there is a high dispersion of management practices within the country. The empirical literature on management practices has established their importance in explaining differences in productivity between and within countries and sectors, and a growing body of experimental evidence supports a causal interpretation. For Greece, the high dispersion of management practices, together with a low average score, could give credence to the argument of little (or no) diffusion of good practices from leaders to laggards.

Similar conclusions are drawn even if we separate overall management score into its broad categories: lean operations; monitoring; target-setting; and talent management. Greece is consistently very near the bottom of the distribution across all four categories.

Delving into the sources of dispersion in management practices, two features stand out. First, Greece has the largest gap in management practices between domestic firms and foreign multinationals operating in Greece. Second, Greece also has one of the largest gaps (the largest in advanced economies) between domestic firms active in Greece only and domestic firms with overseas operations.

Looking into the categories where Greece has the best and the worst performance, relative to the average, points to an interesting pattern: Greek firms do worst in tasks requiring people management, planning and oversight, or requiring synergies, dialogue and collaboration. They do best in tasks requiring decision-making, possibly by a single individual. A potential corollary of this finding is that Greek firms may prevent their employees from exercising judgement and discretion, instead requiring them to follow strict rules and delegate to senior management. Such structures can inhibit firm growth, as larger firms require local decision making and flexibility in responding to shocks.

Taken together, these are consistent with low levels of trust between firms and workers and could correspondingly signal little attachment to the job, low accumulation of human capital, and eventually low productivity and wage growth. This can also have considerable consequences for the viability of small firms when, for example, the founder retires and the succeeding generation shows weak corporate governance and lower managerial quality.

Further analysis reveals that larger firms perform better in all management practices and across sectors while better-managed firms are more productive. The relationship between productivity and management is strong across all subcategories of management indicators (see Figure 2). Given the well-established relevance of management for productivity, the above findings are particularly troubling as regards the long-run growth prospects of the Greek economy.

To sum up, results show a need to improve the alignment of workers’ skills with the needs of industry, in terms of enhancing both skills endowment and the allocation of current skills to jobs. Relevant policies should be closely coordinated while strategic initiatives should be carefully designed and implemented.

On the management practices front, policy recommendations include engaging in changing business culture and management practices in Greek manufacturing firms, i.e. through specific in-firm training programmes, focusing on the managerial skills of firm employees and the selection processes of managers at different levels and promoting joint ventures and other forms of cooperation between professionally organised and managed firms and traditional family-managed firms.

Figure 1: Skills mismatch for high-skilled and low-skilled occupations

Over-skilling Under-skilling

Note: Over-skilled workers are those whose proficiency score is higher than that corresponding to the 95th percentile of self-reported well-matched workers – i.e. workers who neither feel they have the skills to perform a more demanding job nor feel the need of further training in order to be able to perform their current jobs satisfactorily – in their country and occupation. Under-skilled workers are those whose proficiency score is lower than that corresponding to the 5th percentile of self-reported well-matched workers in their country and occupation. High, medium, and low skilled occupations are ISCO occupational groups 1 to 3, 4 to 8 and 9 respectively.

Source: OECD, Survey of Adult Skills (PIACC).

Figure 2: Management scores and labour productivity

Sources: World Management Survey and Orbis.

Notes: Labour productivity is defined as the natural logarithm of operating revenue, divided by the number of employees. Overall management (including all questions) and sub-indices of the questions covering each of the portions of the questionnaire (lean operations, monitoring, target-setting and people management). A full set of the questions can be found at www.worldmanagementsurvey.com.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Greece@LSE, the Hellenic Observatory or the London School of Economics.

*The authors are also pleased to announce the publication of their Research Paper; ‘An Intelligent Industrial Policy for Sustainable Growth’ at the Bank of Greece Economic Bulletin.