At the end of 2023, Greece had an overall inflation rate of 3.7 percentage points in year-over-year terms. After a peak of 12.1% in September 2022 the Greek economy went through a remarkable disinflationary process. At the same time, unemployment was reduced significantly to a single-digit rate for the first time since September 2009 and the Great Financial Crisis. Economists use the term disinflation to describe the slowdown in the rate at which the price level increases. In our previous blogpost1 on this topic, we presented how the overall inflation rate is differentiated across various aspects of the economic activity and we had accurately predicted a 5% yearly change for April 2023 (vs 4.5% realized) at the first stage of this disinflation process. Our goal this time is to attempt to explain the drivers of the core inflation rate. The latter refers to the change in the overall index excluding the volatile components of energy, food, alcohol, and tobacco. Core inflation in Greece rose from a rate of approximately 0.5% in the pre-COVID period to a peak of 7.3% in May 2023 and de-escalated to 3.3% at the end of 2023. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent war between two major energy and grain exporters provide an obvious answer to the increase in food and energy prices. However, we think that further research is needed to determine and quantify the forces that led the core inflation rate to spike and come down subsequently.

Stylized facts and theory

During the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and the following lockdowns, consumers adjusted their spending patterns to consume mainly tradable goods. This is considered a major reason for the initial spike in the core inflation rate. At the same time, supply chain bottlenecks emerged as pandemic-related restrictions amplified, labour shortages spread across key sectors and major ports around the world were seriously congested. Governments and central banks responded to the sudden stop in economic activity and provided ample liquidity and fiscal transfers to stimulate the economy2. Greece3 belonged to the developed countries that mobilized generous support packages towards businesses and households to prevent demand from collapsing.

Yet, what differentiated Greece from the rest of its peers was the amount of ‘’slack’’ in the economy. In contrast to the majority of the developed economies, Greece was exiting a decade-long crisis with a tremendous impact on the real economy. By ‘’slack’’ we commonly refer to the amount of unused production capacity in the economy with unemployment being the most obvious example.. Standard economic theory indicates a negative relationship between ‘’slack’’ and the inflation rate and a positive relationship between the inflation rate and inflation expectations. Therefore, the parallel drop of the inflation and unemployment rate during 2023 was an unusual phenomenon. The expectations relationship can be interpreted as follows: businesses will increase their prices in anticipation of higher prices for their inputs.

Empirical Exercise

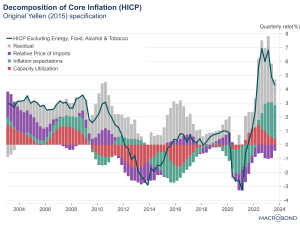

To quantify these relationships we are going to use a version of a fairly simple model that was first introduced by Janet Yellen, by then Federal Reserve Chair4. Following the original model, we estimate core inflation as a function of lags of itself, inflation expectations, relative import prices, and production capacity utilisation as a measure of the ‘’slack’’ in the economy. Figure 2 shows the contribution (in percentage-point terms) of each factor to the core inflation rate. During the pre-2009 period, the economy was working near the high-end of its historic capacity utilisation rate and the prospects for development appeared to be positive. As a result, capacity utilisation and inflation expectations contributed positively to the core inflation rate while during the following recessionary period for the Greek economy, both factors pushed inflation lower. However, this simple model which performed reasonably well until 2020, was unable to attribute the inflation surge of the post-lockdown reopening of the economy to the aforementioned factors. This becomes obvious in Figure 2 where the grey area of the bars that represent the unexplained part of core inflation, reaches unusually elevated levels compared to the previous years. Therefore, we conclude that there must be another factor that accounts for this rise in core inflation.

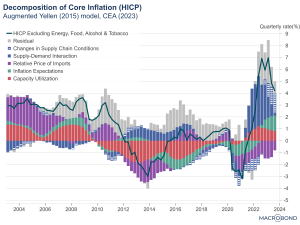

To explain the residual part, we follow the modification of the Yellen model, proposed by the White House Council of Economic Advisers5. We extend our initial specification by including a measure produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to capture global supply chain pressures such as changes in international shipping costs, supplier delivery times or backlogs in completing orders by firms. Given the importance of internation trade for the economy and inflation this indicator can be very informative. Taking into consideration the fact that the Greek Economy recorded a strong recovery of the demand side at a time when supply was stressed to an unprecedented level, the revised model includes a variable for supply-demand interactions.. Finally, our revised model includes a variable that captures the changes in supply chain conditions.

As it becomes apparent in Figure 3, our revised model can explain a large part of the residual during the initial inflation surge as well as the recent disinflation. Capacity utilization continued to rise after the peak of the core inflation rate in April 2023, reaching pre-2008 levels and contributing positively within the pre-crisis levels. On the other hand, relief in the global supply chain pressures from 2022 and onwards was so dramatic that made the Supply-Demand interaction term fall within the historical range even as demand was growing. As a result, the largest part of the core disinflation process happened due to normalisation in the world supply chains. Lastly, it is worth mentioning that the lift-up in inflation expectations due to the recent inflation episode made this factor contribute positively after nearly a decade. .This is not necessary bad for the economy and inflation however, it is something we believe policy-practitioners should monitor carefully.

Conclusions and important caveats

Contrary to the historical experience and conventional wisdom that assumed for core inflation to come down substantially, there has to be a significant slowdown in economic activity, unemployment has fallen together with inflation rate. According to our model this unusual phenomenon can be attributed to the normalization of supply chains in the aftermath of Covid-19 disruptions. However, the Greek economy appears to operate near its pre-crisis historic production capacity. This makes the economy vulnerable to unpredictable shocks in the supply chains that could fuel a resurgence of the inflation rate and derail the path to 2%. For instance, a months-long delay in the reopening of the Red Sea trading route could jeopardize an economic and inflationary hit. Given the unpredictable nature of supply shocks and the historically small contribution of expectations, the implied policy recommendations are mainly directed towards the production capacity of the country. Measures that can increase labour force participation and promote better job-matching efficiency or productivity-enhancing investments could provide resilience in future shocks. As US Representative Kevin Brady noted “Inflation destroys savings, impedes planning, and discourages investment. That means less productivity and a lower standard of living.”

Secondly, even though our modified model explained a large part of the recent core inflation surge, the remaining residual is a call for better modelling exercises and alternative approaches. Recent evidence from the ECB6 points to increased unit profit growth above the growth rate of the unit labour cost.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Greece@LSE, the Hellenic Observatory or the London School of Economics.

References

Short-run Inflation dynamics in Greece: are we finally past the peak? Fountas, Malkidis, Panagiotidis (2023) – Greece at LSE

Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. IMF (2021)

The fiscal response to the economic fallout from the coronavirus. Bruegel, November 2020

Inflation Dynamics and Monetary Policy, Chair Janet L. Yellen, September 2015, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Amherst, Massachusetts

Disinflation Explanation: Supply, Demand, and their Interaction, White House CEA, November 2023

Inflation and competitiveness divergences in the euro area countries, Filip, Momferatou, Setzer, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4/2023