Bronwen Manby is an independent consultant and Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Human Rights at LSE. She previously worked for the Open Society Foundations, which have supported advocacy on the right to a nationality in Africa. This article originally appeared in African Arguments.

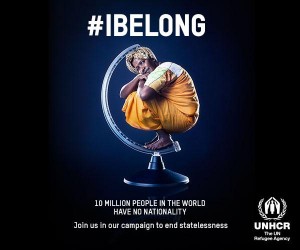

On 4th November 2014 the UN launched a global campaign to end statelessness within ten years. I confidently predict that the result of this campaign will be to ‘increase’ statelessness by many millions of people. This is not because I think that the campaign is misconceived — far from it — but because the statistics on the numbers of stateless persons are currently so inadequate that one of the main impacts of greater attention to the issue will be that currently uncounted populations will come into focus.

On 4th November 2014 the UN launched a global campaign to end statelessness within ten years. I confidently predict that the result of this campaign will be to ‘increase’ statelessness by many millions of people. This is not because I think that the campaign is misconceived — far from it — but because the statistics on the numbers of stateless persons are currently so inadequate that one of the main impacts of greater attention to the issue will be that currently uncounted populations will come into focus.

This is a good thing. At the same time, the Global War on Terror, so-called, is bringing a huge push to improve documentation of populations. The effort to ensure that all are documented will certainly mean that some who thought they were nationals, or who got by as best they could, will find that they cannot get the new documents: that they are stateless. The risk is that this second initiative may overwhelm the first.

What does this mean for Africa?

Since 2006, the UNHCR has begun to count the populations who are stateless (or of undetermined nationality) around the world. For Sub-Saharan Africa the number published in the agency’s Global Trends report for 2013 was the strangely precise 721,303. This total was made up almost entirely of numbers for Côte d’Ivoire (700,000) and Kenya (20,000), with the 1,303 coming from Burundi (1,302) and Liberia (a single person recorded). A further six countries were marked with an asterisk, indicating that statelessness is known to be a significant, but unquantified, problem: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Madagascar, South Africa, and Zimbabwe.

The figure of 700,000 for Côte d’Ivoire is in fact a number supplied by the new(ish) government there, made up of “descendants of immigrants” (400,000) and “children abandoned at birth” (300,000). Notoriously, Côte d’Ivoire’s nationality code failed to provide any clarity on who became Ivorian at independence; while since 1972 the country has had no provision in its law attributing nationality to children of unknown parents. But it is clear that the number of stateless persons is pulled out of thin air, with no basis in any statistical method.

The number for Kenya is equally unscientific, though people of Nubian, Somali and other groups undoubtedly have problems in obtaining recognition of Kenyan citizenship; problems which have been exacerbated by the series of bombings in Nairobi attributed to people of Somali ethnicity whether with Kenyan citizenship or not, and not solved by provisions in the 2010 constitution for persons established in Kenya since independence to apply for recognition of nationality.

For the other countries, the numbers may add up to several hundreds of thousands of additional people; depending on the methodologies used. In DRC, the nationality status of the entire Banyarwanda population is generally disputed, and their total numbers may be up to one million according to some assertions (though nobody knows); albeit some will certainly have documents showing Congolese nationality.

In Zimbabwe, the extremely literalist application of rules prohibiting dual nationality left tens of thousands without recognition of Zimbabwean citizenship and struggling to obtain documents from any other country; many were unable to do so. The new 2013 constitution permits dual citizenship except for those naturalising as Zimbabwean, but the Citizenship Act is unaltered since the last amendments in 2003, with no proposals for reform on the table, leaving much room for confusion.

Ethiopia and Eritrea are still failing to deal with the nationality fall-out from their separation and two year war, with many thousands of people of Eritrean descent in Ethiopia still facing challenges in getting Ethiopian documents, though they are not Eritrean. Madagascar has a long-standing population of several tens of thousands of people of Indian descent who have struggled since independence to have recognition of Malagasy nationality.

The fact that South Africa features in the list may surprise: South Africa’s constitution provides for every child to have the right to a nationality from birth, and its citizenship act states that a child born in South Africa who can claim no other nationality is South African. But the law also provides that any such child must have formal registration of birth, and the government (after a major push since 1994 to increase birth registration) is now making it more difficult for foreigners to register the birth of their children, and is contesting applications for South African citizenship in court.

We only know about these cases because national organisation Lawyers for Human Rights is providing legal assistance: other African countries without a human rights group making a systematic effort to help those who cannot get nationality documents do not have the same level of attention, and the problem of statelessness remains invisible.

But the more surprising thing about the UNHCR list is the countries that are missing: Sudan, for example, where the secession of South Sudan in 2011 has created a population of several hundred thousand at risk of statelessness, mainly persons of South Sudanese origin whose Sudanese nationality has been automatically removed by law.

Nigeria’s constitution creates a pure descent-based system of citizenship, with emphasis on the idea of “indigeneity”, but no legal definition of “indigene” and no system for obtaining proof of nationality. In practice, proof of Nigerian-ness is a “certificate of indigeneity” issued by a local government area — a document for which there is no legal authority. With the concern over Boko Haram and the introduction this year of a system of biometric ID cards there is every risk that blameless individuals belonging to “suspect” social groups will find themselves suddenly defined as not Nigerian.

Meanwhile, a population of more than a hundred thousand living on the Bakassi peninsula transferred to Cameroonian sovereignty by the International Court of Justice are now left without recognition or documentation of either Cameroonian or Nigerian nationality.

There are also some thousands of former refugees from Liberia, Sierra Leone and Rwanda still living in their host countries after the invocation of the cessation clauses under the 1951 Refugee Convention. They now have no continued recognition of refugee status, nor of their original nationality, nor of the nationality of the country where they now live.

The Tanzanian government has blown hot and cold over the grant of nationality to around 170,000 Burundian refugees from the 1970s who were approved for citizenship but never received their documents; in the last few weeks, certificates of naturalisation have again been promised.

Other groups at risk of statelessness across all countries in Africa include persons following a nomadic pastoralist lifestyle, who often face difficulties in obtaining recognition of nationality in any of the countries where they habitually graze their livestock; members of ethnic groups that cross international borders, where both states see them as belonging to the other; those displaced by conflict, whether internally or across international borders, especially those who are not registered by UNHCR; children of national mothers and foreign fathers, in countries where gender discrimination is still applied; and trafficked, abandoned and orphaned children, including especially those born out of wedlock, whose identity is not documented and who cannot establish nationality on reaching adulthood. Although members of these groups may be theoretically eligible for nationality under the law, they often face insurmountable problems in obtaining recognition of nationality in fact.

Why does this matter?

A couple of quotes may suffice. A member of a Fulani pastoralist community living in a village tellingly named Sabon-Gari (“strangers’ quarter”) in the far north of Benin interviewed in May of this year highlighted the consequences even for those apparently most remote from state structures: “Because no country recognises us, we live as if we were in prison”. Rebel leader — and future prime-minister — Guillaume Soro of Côte d’Ivoire emphasised the foundation of the civil war in that country in the right to a nationality: “Give us our identity cards and we’ll hand over our Kalashnikovs”. For both individual rights and political stability, nationality law matters.

The truth is that it is almost impossible to come up with definitive numbers for stateless persons, or those whose nationality is currently undocumented and who may be stateless. The line between those who have a nationality and those who are stateless is not necessarily a clear one, and it may only gradually become apparent that a person is, in fact, “not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law” (the official international law definition).

For me, it is enough that UNHCR simply notes that particular countries have potentially significant numbers of stateless persons, and identifies the reasons why: far better to concentrate on addressing the problems than trying to get the ‘correct’ statistics; and, in any event, identification as ‘stateless’ may not be a helpful outcome for the people concerned, who simply seek recognition of nationality by the country where they have always lived.

The good news is that the African Union institutions are beginning to recognise this problem, as well as the UN. As a result of advocacy from a group of civil society organisations under the banner of CRAI, the Citizenship Rights in Africa Initiative, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights adopted a resolution in April 2013 calling for wider recognition of the right to nationality and commissioning a study on the problem. In May 2014, after considering the report, the Commission resolved to draft a protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the right to a nationality in Africa.

This is progress: nationality law has been left up to state discretion for too long, and the lack of real norms has left individual countries to adopt exclusionary laws in a human rights vacuum. In the meantime, the UNHCR campaign to end statelessness will surely help, by shining a spotlight on the issue and putting more pressure on states to address the issues — even as it will also surely increase the numbers recognised to be at risk.

Great post.