The UN has proposed that providing a “legal identity for all” is one of its Sustainable Development Goals, yet proposes to measure progress against this goal simply in terms of birth registration rates. Edgar A. Whitley and Bronwen Manby explore the complex relationship between birth registration and legal identity from a legal and management perspective.

Edgar A. Whitley is an Associate Professor (Reader) of Information Systems at the LSE Department of Management and Bronwen Manby is a Visiting Senior Fellow at the LSE Centre for the Study of Human Rights.

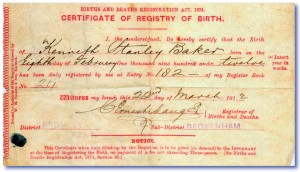

Questions of identity and documentation have become increasingly important parts of the global policy agenda in recent years and are included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that will replace the UN’s eight Millennium Development Goals. In particular, goal 16.9 is: “By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration”.

The UN Statistical Commission (UNSC) has proposed a series of indicators to enable the UN to assess progress towards meeting the various SDGs. The national statistical offices of UN member states were then asked to rate each of the proposed indicators to determine how feasible it would be to collect statistics relating to the indicator, their view on the suitability of the indicator for the goal and how relevant they thought the proposed indicator was to the goal.

In the context of SDG 16.9, the proposed indicator is “Percentage of children under 5 whose births have been registered with civil authority”. This indicator was given the highest possible rating by member states. Versions of this indicator are already in use; for example, UNICEF report that over 50 million children in 2006 had not had their births registered by the age of five.

The proposed indicator, however, only covers part of SDG 16.9 and says nothing about the broader meaning of “legal identity”.

Following last year’s International Identity Management Conference in Seoul, South Korea, two recent meetings have brought together practitioners, activists and academics from previously unconnected worlds to discuss the provision of legal identity. These meetings have helped us begin to unpack the complexity of this important policy goal.

At the first, The Hague Colloquium on the Future of Legal Identity, “social scientists and policy researchers examine[d] the various forms of civil registration and identification currently used and introduced around the world to consider the opportunities and implications of the choices that poor states, in particular, currently face”, especially in relation to new forms of biometric identification. The second meeting was the launch event for the Lancet series on Counting Births and Deaths, an update to their 2007 series on the importance of civil registration for public health and for development more generally.

Presentations at these meetings highlighted the diverse range of actors with a stake in “legal identity”. For example, states worried about national security, documented and undocumented migration are tightening up on identity verification and control, whilst development agencies highlight the importance of identification and the “data revolution” for development and economic empowerment, and public health professionals want better documented data on causes of death. Child rights activists and UN agencies highlight the importance of birth registration for child protection and as a step towards an end to statelessness. Meanwhile, private companies involved in the production of biometric identity documents want to sell their products, frequently to governments who are unsure what policy objectives their identity policies are intending to address.

The more we learned at these workshops, the less clear the nature of “legal identity” in the proposed goal became, beyond birth registration itself. These complications ranged from the human-rights-legal (BM) to the socio-technical implementation of the administrative systems (EAW). For example, although a high level panel advising the UN has stated that a child’s lack of birth registration means that they do not have a legal identity, others argue that legal identity exists whether a birth is registered or not. In practice, lack of formal evidence of birth registration blocks access to education and other services in some countries. When the World Bank says that “identification for development” and new digital identity systems “can help developing countries leapfrog to more efficient 21st century systems”, how do the different purposes for which identification is used relate to each other?

Similarly, whilst birth registration creates a permanent record of the child’s existence and some basic facts about the circumstances of the child’s birth, this doesn’t necessarily confer a nationality on the child, the most important “legal identity” of all for that child when it becomes an adult. Although Article 7 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child provides that every child has the right to acquire a nationality, it and other human rights treaties are unclear on the state that has the duty to provide that nationality, except in limited circumstances, and no form of birth registration or national identity card system can solve problems of exclusionary nationality laws.

The SDG goal does not address this conundrum. Moreover, a poorly implemented civil registration system might, perversely, make claiming a particular nationality less rather than more straightforward. For example, refugees from Côte d’Ivoire fleeing violence targeted at people believed not to be “really” Ivorian, whose children receive a birth certificate from a neighbouring country, may fear that the same document could be read in future as proof that, as alleged, the child is not Ivorian.

Additional questions emerge based on how the administrative systems that might support SDG 16.9 are implemented. There are an increasing number of initiatives, often donor-supported, to create new identification systems in poor countries. These encompass both “functional” identity applications such as electoral rolls or registration of beneficiaries of particular public services; and also “foundational” applications such as national identity cards. Although there has also been a recent drive to support improved traditional civil registration systems for births, marriages and deaths, it seems that the temptation is to neglect this cheaper and more comprehensive approach in favour of the newer technologies.

Where these new identity applications cannot draw on (non-existent / poor quality) civil registration data, they rather rely on other characteristics, especially biometric “uniqueness” based on fingerprints or iris scans, as a way of eliminating multiple voting or multiple attempts to benefit from social grants. But all biometrics have limitations that may “exacerbate existing inequalities” and run counter to the spirit of ensuring a “legal identity for all”. Moreover, they cannot address the fundamental question of whether a person is who they say they are, or is entitled to vote, or is a citizen; only whether the person holding the relevant ID card is reasonably certain to be the person to whom the card was issued.

Additionally, these applications are all too rarely integrated with other “legal identity” applications and it is often legally (and practically) unclear how they relate to each other. For example, is a voter registration record considered as proof of “legal identity” (including citizenship) on an ongoing basis or only as an entitlement to vote in a single election? Can a biometrically unique Aadhaar number issued to Indian residents satisfy the know-your-customer requirements associated with telecommunications subscriber verification measures?

Despite – or because of – all these challenges, we believe that the proposed SDG goal is an important one that gets at many critical questions for development and human rights. But it is important to clarify what is meant by “legal identity”, how it relates to birth registration, and how the UN can measure progress against these goal(s). Despite all the excitement about new technologies, it seems that people from many different backgrounds agree that civil registration is an absolutely important first step.

The authors of this article are working with colleagues who participated in the Hague Colloquium with the intention of providing more detailed recommendations. If you wish to join this process, please contact them here.