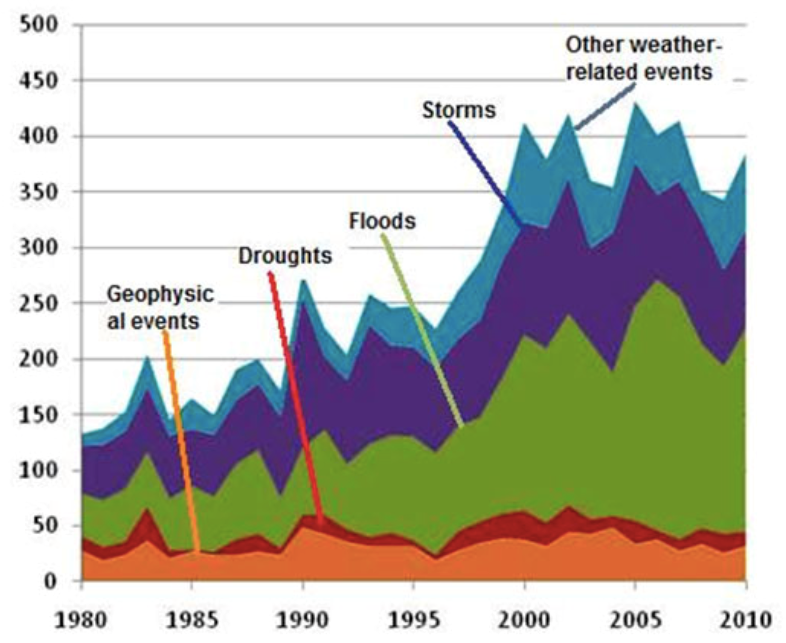

Both humanitarian responses to disasters and the vulnerability of a population to the effects of a disaster are often gendered. This is the case particularly for women in crises, though it’s important to be mindful that gender issues are not limited to women or femme-identifying people. This article only provides a brief overview of some of the issues NGOs and IGOs face today in managing disasters, but it is important that the global humanitarian system begin to pay more attention to gendered vulnerability during humanitarian crises as we face an increasing number of climate-related threats every year. We can only begin to protect the human rights of vulnerable women in the field if we understand the factors that make them vulnerable to abuse and neglect in the first place.

Women and Survival During a Crisis

Ariyabandu (2005) highlights several culturally embedded divisions and gender-based prejudices as the key to understanding female vulnerability in the aftermath of a disaster. For instance, in countries where conservative dress is the norm cumbersome clothing such as saris and burkas that cannot be removed due to cultural and religious expectations reduce a woman’s chance of surviving a disaster by limiting mobility. Moreover, Neumayer and Plümper (2007) reported that a lack of practical skills can make women more vulnerable in some crises. During the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami the number of Sri Lankan women and girls who did not have swimming and tree climbing skills in contrast to their male peers significantly affected the female survival rate.

Societal expectations in socially conservative societies can also affect the mobility of women during natural disasters. For example, women are more likely to act as caregivers than men during a crisis, leading to a lack of mobility for women who care for the elderly or for children during and after a disaster. A patriarchal societal structure may also mean that women refuse to leave their homes without male permission, even in the case of emergency, which can lead to a higher death rate amongst women (Parida, 2015, on Sri Lanka). Finally, in households where family finances are controlled by men, unmarried women or women who are widowed or separated from their husbands or fathers may lack the financial resources or know-how needed to facilitate survival, and a male ‘first’ distribution of food and resources by aid providers can lead to malnutrition and starvation for these women (Parida, 2015).

Female Vulnerability Post-Crisis

Post-disaster, vulnerability remains gendered as gender roles become elevated in the wake of crises, particularly for young unmarried girls living in temporary accommodation or refugee camps. For instance, Grabska (2011), reporting on the Kakuma Refugee camp in northern Kenya, found that forced marriage rates rose as ‘traditional pressures’ on girls to marry and leave the family home were exacerbated by a lack of food and resources in the aftermath of the disaster. The young girls in the camp also increasingly began escaping domestic violence, family pressures and arranged marriages through elopement with their camp boyfriends or even by committing suicide (pg. 90). Overall, the surveillance of women’s bodies, the restriction of their movements, and societal censures tend to be heightened post-disaster under the guise that women are to be ‘protected’ as the guardians of the honour and cultural traditions of the family and community. Women in temporary accommodation and refugee camps are also far more vulnerable to sexual harassment and rape with long lines for food and water leaving women exposed in an already unpredictable and tense environment.

Gender and the Humanitarian Response

Gender inequality during and post-disaster is likely augmented by humanitarian responses which are often themselves gendered. Hyndman and De Alwis (2003) point out several ways in which the humanitarian response system is structurally gendered in the opening of their paper. They claim that gendered concerns are often treated as a luxury when implemented, as opposed to an essential part of the planning process This is problematic because as evidenced above gender is a significant and complex factor in an emergency that can determine survival, and post-disaster wellbeing. International NGOs frequently appoint female gender coordinators without any male counterparts, or, where there is no trained gender coordinator available, fall back on junior female members of staff on the assumption that as a female, she must be sensitive to gendered issues. As Hyndman and De Alwis put it, ‘to include “gender balance” or a “gender analysis” in the evaluation of a project . . . without integrating gender into the very conception of a project, is to miss the point’ (pg. 215). Hyndman and De Alwis claim that ‘such practices only serve to marginalise the place of gender analysis and politics within aid organisations’ (pg. 219) as the problem is treated as a purely female one rather than a phenomenon in which men are part of the problem and solution.

Humanitarian responses are also gendered through the attitudes of humanitarian aid workers towards women in the field. Grabska (2011) accuses humanitarian actors of ‘essentialising women . . . as more peaceful, victims of gender-based violence, vulnerable to subordination, without access to rights, disadvantaged and at risk’ (pg. 90). Using the case study of the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya, one of the largest camps in the world with a population of 191,500 registered refugees and asylum-seekers at the end of August 2019 (ref. UNHCR), Grabska explains that this ‘essentialising’ of the female experience in times of crisis can mean that the capabilities of women are overlooked as key local responders in favour of local men. This assumption can often be to the detriment of the overall success of the humanitarian response, as Lafrenière et al (2019) provide evidence for the foundational role of women’s organisations in post-disaster relief.

Conversely, the essentialising of women as victims that need economic and social empowerment at any cost can lead to more harm than good. For instance, the distribution of food ration cards to women by the UNHCR in the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya sought to empower the women of the camp by improving their position within the ‘patriarchal bargain of the household’ (Grabska, 2011, pg. 91). An interesting quote from one of the refugee men mentioned in Grabska (2011) stated that ‘before we could control the woman through the access to food, but now, since she can go to the UN directly, the woman has more power in the family and you might feel that you are not a man’ (pg. 89). This disruption to the status quo of traditional gender relations paired with the introduction of workshop initiatives that sought to educate the camp’s men on gender equality tragically worsened the relationship between the men and women in the camp and lead to an increase in domestic violence. Grabska makes clear that truly effective gender policies must be sensitive to non-Western conceptions of equality whilst also bearing in mind the risk of gendered humanitarian responses.

The case studies in Sri Lanka and Kenya serve to demonstrate the real need for gender sensitivity in crises, as both the survival and living conditions of women hang in the balance. The logistical complexity of many crises, the cultural backdrops of the disaster areas, and the speed at which NGOs, governments and humanitarian agencies often have to respond to disasters make it extremely difficult to be effectively sensitive to the gendered elements of a disaster response. However, an increase in the allocation of resources and attention to gendered issues would be a start, in particular an improvement in the quality of gender training and an upsurge in the recruiting of both male and female gender coordinators so that gender is not brushed aside as a female-only issue. The continued preventable suffering of women in disaster zones demands that the global humanitarian network address gendered issues as matters of survival, rather than secondary cultural ones when conducting a disaster response.

References:

Ariyabandu, M. (2005). Addressing Gender Issues in Humanitarian Practice: Tsunami Recovery. In: Special Issue for International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva: UNISDR,2009. (Retrieved From: https://www.unisdr.org/files/9922_MakingDisasterRiskReductionGenderSe.pdf)

Freedman, J. (2010). Mainstreaming Gender in Refugee Protection. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 23 (4)

Grabska, K. (2011). Constructing ‘Modern Gendered Civilised’ Women and Men: Gender-Mainstreaming in Refugee Camps. Taylor and Francis Group, Vol. 19 (1)

Hyndman, J., and De Alwis, M. (2003). Beyond Gender: Towards a Feminist Analysis of Humanitarianism and Development in Sri Lanka. Women’s Studies Quarterly, Vol. 31 (3/4)

IASC Reference Group on Gender and Humanitarian Action (2018). The Gender Handbook for Humanitarian Action [online]. Available at: <https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2018iasc_gender_handbook_for_humanitarian_action_eng_0.pdf>

Lafrenière, J., Sweetman, C., and Thylin, T. (2019) Introduction: Gender, Humanitarian Action and Crisis Response. Gender & Development, Vol. 27:2.

Neumayer, E., & Plümper, T. (2007). The Gendered Nature of Natural Disasters: The Impact of Catastrophic Events on the Gender Gap in Life Expectancy, 1981–2002. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 97.

Nguyen, H., T. (2019). Gendered Vulnerabilities in Times of Natural Disasters: Male-to-Female Violence in the Philippines in the Aftermath of Super Typhoon Haiyan. Violence Against Women, Vol. 25 (4).

Parida, P., K. (2015). The Social Construction of Gendered Vulnerability to Tsunami Disaster: The Case of Coastal Sri Lanka. Journal of Social and Economic Development, Vol. 17 (2).

Fig. 1: Raghav Gaiha, Kenneth Hill, Ganesh Thapa ‘Have Natural Disasters Become Deadlier? ASARC Working Paper 2012/03 at: https://crawford.anu.edu.au/acde/asarc/pdf/papers/2012/WP2012_03.pdf

UNHCR: Inside the World’s 10 Largest Refugee Camps: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=8ff1d1534e8c41adb5c04ab435b7974b

good article

good