The REF’s impact criteria aim to encourage academic engagement with the business world. Government must provide an incentive for businesses to reach out to academics, and innovative publishing practices are key to this two-way relationship, writes Simon Linacre.

The REF’s impact criteria aim to encourage academic engagement with the business world. Government must provide an incentive for businesses to reach out to academics, and innovative publishing practices are key to this two-way relationship, writes Simon Linacre.

A decade ago Bradford School of Management held a two day conference on Corporate Social Responsibility where academics delivered papers one day and practitioners the next, with a view to bridging the gap between the two fields. Suffice to say it was a very long couple of days. The demands of rigour and academic style have never sat well with the needs for brevity and bullet points in the corporate world. But how do we begin to close the gap? I have attended dozens of conferences that have tried to tackle this very problem with little progress being made while working for Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. However a recent event held in London aimed to engineer some real change with innovation at the core of its brief.

Mind the Gap

A group of scientists and management academics based at Kellogg Business School at Northwestern University in Chicago have for a number of years successfully reached out to the corporate community to help solve business problems through innovation. The Global Advanced Technology Innovation Consortium (GATIC) holds workshops on innovation and has developed a strong international network consisting of universities such as Cambridge and the National University of Singapore, as well as firms such as IBM and Siemens. One of GATIC’s current projects, in collaboration with Emerald, is to investigate the development of new paradigms in academic communication, specifically in the areas of business and management where the gap is more of a chasm.

Hence the Knowledge Sharing and Innovation (KSI) event in London. You might question that there is a problem at all. But if there is a disconnect – and I believe there is – how does it benefit both parties to be more closely aligned? The bold step by the UK government in its Research Excellence Framework (REF) in 2014 to require universities to display how much impact their research has had outside the confines of academic journals is evidence that it at least thinks there is a problem, and currently UK universities are scratching their heads trying to understand how they can show this, as 20 per cent of research quality assessment will depend on it. In a world of budget constraints, the government, at the very least, wants to see some return on its investments in UK higher education.

One approach recounted at the London event, unfortunately, was the decision of one UK business school to avoid the problem altogether. This school has simply increased the number of publications in top-rated journals it demands of its faculty members, thereby hedging the impact of the, er, ‘impact’ agenda.

Serious games

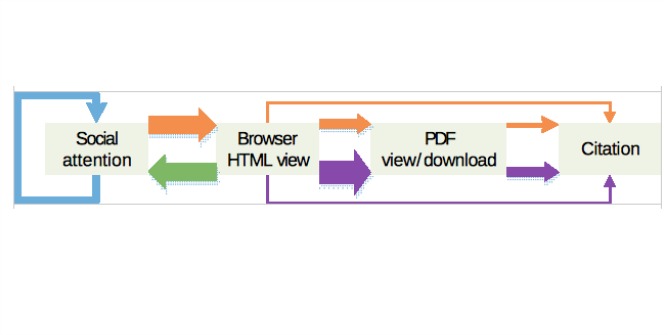

One could conclude that if universities have decided to game the system, then there must indeed be something to address, and partly this is down to vested interests. As one delegate noted, there is an inverse correlation between the highest quality journals in business and management, typically identified by their inclusion and high ranking on the Thomson Reuters’ citation indices (usually referred to as ‘ISI’), and their accessibility by those working in these areas. Currently there is little or no career incentive for an academic to write for a publication read just by practitioners, or that doesn’t figure high up in journal rankings, and as long as that structure exists, the gap is unlikely to close between the two camps.

So how to change things? A journalism professor at KSI encouraged an audience-focused approach, committed to understanding the needs of practitioners much more thoroughly. This led to an observation by Fiona Godsman, CEO of the Scottish Institute for Enterprise, that academic publishing had all the best information to hand for business, but was aimed at just the 1% of the population or less in the shape of academics. The challenge, therefore, is for the publishing process to transform and deconstruct the information available and make it relevant to the other 99%.

Push and pull

What many people identified at KSI was not just the need to provide content in new ways to new people, but to also ensure a strong pull from the side of business. New search functionalities, web analytics and the ability to mine ‘big data’ for new insights could, according to a contributor from IBM, help identify collaboration opportunities between the two camps and help automate the increasingly outdated norms of taxonomies, which serve to inhibit information sharing rather than enable it.

Furthermore, the government was identified as having an opportunity to raise the profile of universities by promoting their output to the world of business, and ensuring that they were engaged properly to academic institutions. The REF aims to address one side of the equation by incentivising academia to give evidence of the impact of their work, however the other side remains a void. Until business is more pro-active in seeking solutions from academics, the divide is likely to remain.

There are, of course, examples where the two worlds collide, such as the much lauded success of Harvard Business Review, The Economist and Emerald’s Management First. However they tend to be the exceptions that prove the rule – only with innovative publishing practises and a more open approach from businesses can greater collaboration occur. And let’s be honest, as university funding is been cut back due to the failings of banks and big business, they need all the help they can get.