Dismayed by news that the Government has embraced the Finch Report findings, Mark Carrigan asks what will happen to authors and early careers researchers who have not yet secured a steady stream of funding and cannot pay the upfront fees required of gold open access.

Dismayed by news that the Government has embraced the Finch Report findings, Mark Carrigan asks what will happen to authors and early careers researchers who have not yet secured a steady stream of funding and cannot pay the upfront fees required of gold open access.

Sometimes I worry that Twitter is an echo chamber, reflecting my own prejudices back at me and shielding me from contrasting views. On other occasions though, I find this same characteristic immensely comforting. Such as when reading that the government has officially embraced the recommendations of the Finch report and finding that other PhD students and early career researchers were just as dismayed by this news as I was. Leaving aside the broader issues pertaining to gold open access, which in practice simply redistributes costs within a broken system without challenging the underlying commercial premise, there’s one particular question posed by this chain of events which is the cause of my current dread about the future of academic publishing: what about the authors who can’t pay?

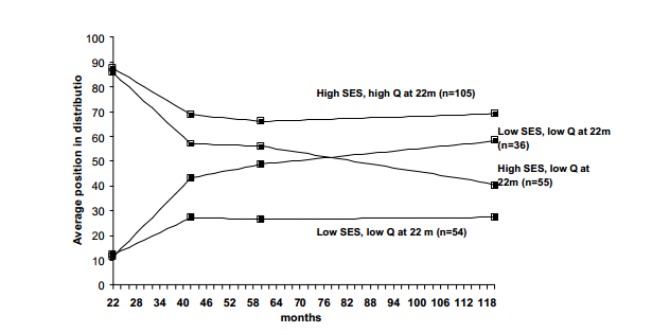

I fear that academic publishing could come to resemble the perilous landscape that PhDs and ECRs are only too familiar with at present. The competition for postdoctoral funding is ever increasing, leading to continual inflation of the things you need on your CV to stand a chance, yet without funding it’s very difficult to actually achieve these prerequisites. Or in other words: the best way to get postdoctoral funding is to already have it. Could we see something similar happening with publications? If authors are dependent on their institutions and/or funding bodies to pay the substantial fees required under gold open access then those who already have a job and funding will find it easier to publish and thereby increase their chances of getting another job and more funding. Much as the post doctoral funding climate creates virtuous cycles, so too will the publishing climate, as a whole swathe of early career academics will find themselves untroubled by article processing charges. From their perspective, open access of this form will be great: it doesn’t pose problems and it means their research is freely available. On the other hand, what of those who find themselves excluded? If your funding is patchy or non-existent how can you compete? Is it even going to be possible to be an independent researcher in any meaningful sense?

In a climate where freelance, part-time and fixed term contracts are increasingly the norm within academia, the extent to which the government’s announcement is retrograde cannot be overstated. Such a radical increase in the dependence of researchers upon their institution has profound consequences for those who do ‘make it’, leaving aside the many who seem likely to be wholly or partially swept aside for the reasons discussed above. With funding bodies increasingly focused around narrow priority areas, often tied to short term political whims to a truly abominable degree, themselves falling into homology with priority areas within universities, naturally aiming to increase their success in winning funding from these bodies, what becomes of research that falls into a non-priority area? What becomes of independent research full stop? Will there be funding available to cover author fees? Will there be conditions attached to it? How will the inevitable rationing work?

Even assuming the best will and highest managerial acumen in the world, these yet unanswered questions paint a picture of the future university, which I find far from appealing. What of the willingness to dissent and speak up at a time when economic instability looks set to continue indefinitely? With academics even more reliant on universities, as one of the two potential sources of author fees, will they be willing to resist? Or will the disciplining of academic labour, already entrenched in multifaceted ways with many personal consequences, simply continue?

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Sciences blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

This post was originally published on Mark Carrigan’s personal blog, which you can read here.

An excellent argument against Finch et al. and Willetts

But it goes much wider: within Universities, within departments, within research groups there will be competition for the money to pay for publications. Many will be told – ‘sorry you can’t publish any more papers this year’, or, ‘sorry, if you want to publish that paper you will have to put it in a cheaper journal’! And on what grounds will those decisions be made – and by whom? (If £50million is to be allocated to this purpose and the average cost per paper is £2000 then British academics will only be able to publish 25,000 papers per annum)

And anyhow, who in the general public will want to read 99% of what academics publish? This is an ill-thought through policy which will do nothing to release academia from the rent-seeking of the big commercial publishers and improve the accessibility of research outcomes to those who want it not one jot

This article outlines my fears, as a PhD researcher, exactly. I can’t imagine my department forking out £2k for me to publish, especially when PhD’s aren’t usually submitted for the REF. Meanwhile, my research “budget” is £200 a year…

But I disagree with Ron Johnston’s comment that ‘who in the general public will want to read 99% of what academics publish?’ Before I started my PhD, when I was working, I was enormously frustrated by not being able to access journal articles. I am still frustrated that many professionals practising in my field of research (community care law – so social workers and lawyers mostly) can’t access research papers about their field of work. So are they. But at the same time, moves towards payment-for-publication would be problematic for non-academic professionals seeking to publish – I can’t see the NHS, or local authorities, or law firms forking out for their staff to publish in journals.

Besides, many journals currently operate systems whereby they have gold open access for some articles where authors have paid, and not for others. This means that university libraries would realistically still have to pay subs for those journals, as otherwise you’re only getting part of the content. So they’re paying twice – once to publish, and once to read.

I don’t have any answers for this. But Gold Open Access looks like yet another shift in academia that will entrench the position of those with established careers, whilst screwing over the precariat at the beginning of theirs.

A good post. And Ron Johnston is right. The only real winners from Finch are the commercial publishers. The public gain a little and universities loose the most. Gold open access allows people to read research, but it does not open up participation in research. It’s not just early career researchers who will suffer, but scholars in poorer countries, independent scholars, those in small institutions, those on ‘teaching only’ contracts etc. I’m sure that industrial tribunals will soon be dealing with cases where individuals have been refused access to publishing fees.

There are plenty of open access journals hosted by universities out there which do not require a submission fee. There is no good reason why all journals could not convert to this model. Detractors point out that someone has to pay for open access, but universities are already paying most of the costs e.g. the salaries of research staff, journal editors, peer reviewers etc. etc. Funds could also be raised by the sale of print copies. A cooperative agreement from universities throughout the world could rapidly bring this change about.