It can be difficult to determine how much data is required for research analysis. Kerim Friedman compares the process to documentary film-making where they typically shoot sixty times the amount that makes the final cut. The concept of a “shooting ratio” underlines the necessity of collecting a lot of data in order to find that one choice nugget upon which hinges the analysis. But collecting data isn’t just about learning, it is also about collecting material that can be used to flesh out a story and make it come alive.

It can be difficult to determine how much data is required for research analysis. Kerim Friedman compares the process to documentary film-making where they typically shoot sixty times the amount that makes the final cut. The concept of a “shooting ratio” underlines the necessity of collecting a lot of data in order to find that one choice nugget upon which hinges the analysis. But collecting data isn’t just about learning, it is also about collecting material that can be used to flesh out a story and make it come alive.

One of the questions I get asked most often by graduate students doing ethnographic research is about how much data they need to collect. I think this is especially troublesome for those who are doing fieldwork somewhere far away, where limited time and funds mean that they will unlikely be able to make a return trip after they return from the field. But even those doing research closer to home want to know “How much is enough?” In answering this question I draw on my experience as a documentary filmmaker.

A “shooting ratio” is “the ratio between the total duration of its footage created for possible use in a project and that which appears in its final cut.” For a Hollywood film, where the scenes are planned in advance, this might be four to one. That is, shooting four hours of footage for every hour of the final film. Now that films have largely gone digital, producers no longer need to worry about the cost of expensive film stock, but it still costs a lot to have actors and crew out for a day and nobody wants to waste too much time shooting the same scene over and over again.

For documentary films, however, it is different. While you usually have a conception in your mind about what the final story will look like, you have to be ready to follow your subjects wherever the story takes you. For this reason the shooting ratio on a documentary film is likely to be more like 60:1, one hour of footage for each minute used in the final film. Some documentary films might even be as high as 80:1, or higher. For Please Don’t Beat Me, Sir!, which is 75 minutes long, we shot over 200 hours of footage. You might interview someone for an hour but only end up using a thirty second sound bite from the whole interview. The problem is, until you are in the editing room, you never know which thirty second sound bite will be the one you need.

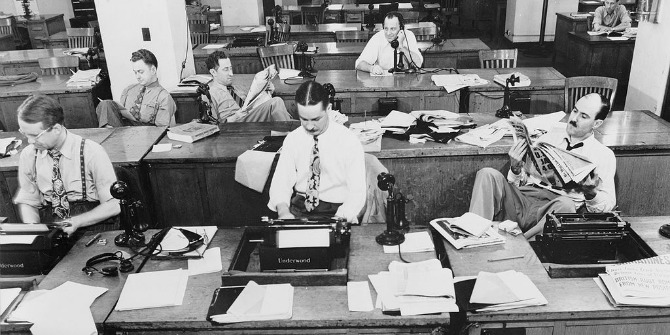

Image credit: Public Domain.

Image credit: Public Domain.

So what does this mean for ethnographic research? Well, one thing you can do is to start writing up your research while you are in the field. If you are editing a documentary film while shooting it makes it easier to see where the story is developing and that helps you focus your shooting on the subjects that are most likely to make it to the final cut. Similarly, if you start writing up your notes every day while in the field you will be better able to focus your efforts. Of course, that isn’t practical for everyone – especially for shorter, more intensive, field trips where you might simply be too exhausted after writing up field notes to think about editing and reviewing them as well.

On a documentary film you might pick a number of subjects that seem to have potential and then only end up using some of their stories in your ethnography. Similarly, by the time you are about half way through your fieldwork you should have a sense of who these subjects might be. Take some time to go over what you’ve collected on each of them and see what gaps you might have left out. For instance, if you are comparing two people with complementary life-trajectories, did you ask them each the same questions? Are there people you only spoke to briefly who might be worth returning to for a more in-depth interview? Here I’m talking about “people” as if it was a documentary film (which tend to be focused on “characters”) but the same questions can be asked if you are focusing on organizations or other topics. The important thing is to have a checklist for the minimal data you need and to make sure you’ve collected at least that much, with some redundancy as well.

Is there a data ratio you can aim for? Unfortunately, it is hard to quantify it in that way. I use the concept of a “shooting ratio” to get students to understand that you need to collect a lot of data in order to find that one choice nugget upon which you will hinge and entire chapter of your dissertation. Another analogy from documentary filmmaking is useful as well: “coverage.” Coverage refers to “the amount of footage shot and different camera angles used to capture a scene. When in the post-production process, the more camera coverage means that there is more footage for the film editor to work with in assembling the final cut.” In a documentary film this might mean shooting the street where a subject lives, as well as the front of their house and the walls of their living room, etc. In ethnographic research you need coverage as well. Don’t just interview a person, but interview their friends, co-workers, family members, etc. Don’t just do interviews, but also collect as much written material as you can about their activities. Also take notes on your impressions of the person and the world they live in, just as if your notes were a camera filming the street on which they live. (And, again, while I am focusing on “people” I think the same ideas apply to ideas and institutions as well.)

One reason I like putting it this way is that it focuses attention on doing fieldwork for the final written ethnography, not just to answer questions in the ethnographer’s head. Too many books I’ve read on fieldwork focus on the ethnographic investigation, even saying that you have enough data when you no longer are learning anything new. I think this is wrong. Collecting data isn’t just about learning, it is also about collecting material that can be used to flesh out a story or argument and make it come alive. Thinking like a documentary filmmaker can help you do that.

This piece originally appeared on Savage Minds and is reposted with the author’s permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Kerim Friedman is an associate professor in the Department of Ethnic Relations and Cultures at National Dong Hwa University, where he teaches linguistic and visual anthropology. His research explores the relationship between language, ideology and political economy in Taiwan. He is a founding member of the group anthropology blog Savage Minds and a documentary filmmaker. His latest film is Please Don’t Beat Me, Sir!.

1 Comments