Co-production – the inclusion of the stakeholders of research into the research process – is often presented as the gold standard for the production of socially relevant high impact research. However, undertaking co-produced research presents a range of challenges and risks that can be overlooked in the rush to engagement and impact. In this post Kathryn Oliver, Anita Kothari, and Nicholas Mays, assess the hidden costs of co-production and suggest that before researchers and research organisation engage with co-production, they should carefully consider what research strategy is most appropriate for their research aims.

Co-production – the inclusion of the stakeholders of research into the research process – is often presented as the gold standard for the production of socially relevant high impact research. However, undertaking co-produced research presents a range of challenges and risks that can be overlooked in the rush to engagement and impact. In this post Kathryn Oliver, Anita Kothari, and Nicholas Mays, assess the hidden costs of co-production and suggest that before researchers and research organisation engage with co-production, they should carefully consider what research strategy is most appropriate for their research aims.

In favour of co-produced research

Many, if not most applied research projects, aspire to some degree of collaboration between researchers and ‘stakeholders’ – research funders, policymakers or practitioners, members of the public and civil society, or other actors, such as patients in health studies. This co-production takes various forms (e.g. consulting on research topics, or working iteratively throughout the research process), and in general, people feel positively about it. Funders often require it, or at least support it, and researchers have argued that it is the most effective way to ensure that evidence is used or translated into practice. People argue that collaborative and co-productive research:

- Creates better-quality research, through improving our understanding of issues, mechanisms, and the research questions of most importance

- Makes it more likely that this research will be acted on

- Is the right way to do research (especially if publicly funded), being more inclusive and less elitist

- Makes potential users feel more empowered, trusted and more persuaded of the importance and veracity of the research findings.

Facing up to the challenges and costs of co-production

Undoubtedly, making research more relevant and used (impact) is the aim for many applied researchers, and their attempts to do so and document this are laudable. However, there is a need to help uncover if, when, and how collaboration is the best way to achieve this (normative) aim.

Firstly, there is very limited empirical evidence about whether collaborative research does lead to improved uptake of findings – even if we could agree what that looks like in reality.

Secondly, collaborative research brings significant challenges. Collaborative research may be more uncertain, slower, or less innovative than non-collaborative research. These challenges may be experienced throughout the research process, as the table below indicates.

| Challenges which may arise | Costs | |

|---|---|---|

| Developing mixed research teams | Stakeholders not homogenous, and can disagree | The research process may take more time compared to a traditional research process |

| ‘Usual suspects’ can take over, where coproductive discussions are dominated by certain individuals | Shared decision-making is threatened when process dominated by certain voices or interests | |

| Framing research questions | Stakeholders and researchers may have different priorities and values | Damage to interpersonal or organisational relationships |

| Useful research can lack originality | Damage to research careers | |

| Research can be co-opted by partners, for example, to justify status quo or historical decisions | Damage to researcher independence and credibility | |

| Collecting data | Researchers may pressure stakeholders to allow their organisational resources to be used to facilitate data collection –e.g. using staff time or applying pressure for site access | Damage to interpersonal or organisational relationships, particularly with more powerful stakeholders |

| Analysing and interpreting data | Stakeholders may want to know which participant agreed to participate or what they contributed to the dataset | Violation of research ethics obligations |

| Stakeholders may want to help analyse the data | Researcher needs to train stakeholders and format data in an appropriate way to conform with research ethics obligations | |

| Formulating recommendations | May be little agreement about the importance of research | Findings are misrepresented |

| Researchers may be pressed to frame findings in particular ways | Damage to researcher independence and credibility | |

| Disseminating research | Researchers or stakeholders may be prevented from sharing unwanted findings | Damage to researcher independence and credibility |

| Stakeholders may want to share findings before researchers are ready | Damage to the credibility of the research process | |

| Implementing change | Tension between advocating for research, or advocating for policy/practice changes | Can damage relationship with practice or policy colleagues |

| Researchers show little interest in providing assistance with implementation efforts | Implementation of research findings fail |

Table 1: Challenges and costs of coproduction

Finally, there are other very significant potential costs of co-production, which, in our experience are often unequally borne by junior/untenured/female members of staff. These include:

The practical and administrative burden required to arrange meetings with busy people for whom research is not their primary activity. This often requires interpersonal skills and the ability to manage group dynamics, for which academics can be ill-equipped.

Stressful interpersonal interactions: these can be dismissed as mere relational difficulties. However, co-produced research heightens the risk of disagreement, conflict, reputational and power imbalances. The consequences of mismanaging these are severe.

Individual researchers already have to balance their teaching, research and administrative workloads. Developing another set of professional skills and networks to create collaborative research projects with real world impact is an insurmountable barrier for some. Ultimately this suggests that some or all of the co-production activities related to a research project could be better led by a specialist in knowledge transfer and exchange, rather than by members of the research team, an approach which is becoming more widely adopted.

There is also a common perception that taking part in applied, highly collaborative research can lead to researchers becoming, or seeming partisan and biased, or as academic “lightweights” producing little of substance.

The research outputs themselves may also be co-opted to serve the political agendas of others. Co-produced research findings (possibly no different from any research) can be appropriated and used to serve the self-interest of more powerful groups. Some groups lack the skills to engage in the use and promotion of research findings so lose out to more skilled and better connected groups. There is also the risk that co-produced research is more likely than other forms of research to produce findings biased in favour of prevailing norms of what is ‘correct’. This last type of research leads to repetitious, ‘safe’ research

What do we need to do differently?

We may be able to avoid some of these costs, or they may be an intrinsic part of collaborative processes, in which case we need to work out the best balance between costs and benefits.

Armed with a better understanding of the costs and benefits of co-production, those planning new projects should be much better placed consistently to ask themselves:

- What is everyone bringing to the table? For example, policy-makers and funders bring money, knowledge of the political context, pressure for answers; researchers bring topic and methodological expertise; the public and patients bring their experiences.

- Under which circumstances are these resources needed, for what purpose, and at which stages of the research process? For example, when is it better to have patient representatives articulate the user perspective rather than derive understanding from a systematic review of patient experiences?

- What are the costs, and how will they be borne and defrayed by those involved?

- How will decisions about the direction of the research be taken, and how will responsibility and accountability for decisions be shared? Will group dynamics, market forces, formal authority or some other basis be used? In turn, how will this be governed?

In parallel, research organisations and funders also need to consider:

- How to create (co-create) and support the infrastructure and leadership for coproduction

- How to provide training in coproduction, and help interested researchers and funders take this seriously as a necessary skill

- How to reward good practice, and to recognise the work coproduction may take even if it does not lead to research impact

- How to evaluate the potential impact(s) of coproduction

- How to ensure that coproduction supports diversity and quality in research and policy

Conclusion

Coproduction is an exciting approach to research that can, with care, generate truly novel, unexpected findings and impacts. Yet it takes time and investment, and there is still little evidence about how coproduction changes research, policy or practice, or how it compares to alternatives. We think more reflection about how, why and when we do coproduction would be helpful, as would more discussion about how coproduction influences the process of research. And perhaps most importantly, how equitable and fair roles and responsibilities of everyone involved in collaborations can be better supported.

This post draws on the authors’ co-authored paper, The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research?, published in Health Research Policy and Systems and will appear on the Policy Innovation Research Unit blog .

About the authors

Kathryn Oliver’s work sits at the intersections of sociology, STS, policy and health sciences. Following a brief career as a systematic reviewer, she became interested in using empirical means to explore what evidence is used in public policy, how, and by whom. She is particularly interested in how evidence use influences both research and policy practices, and is coordinating a multidisciplinary initiative, Transforming Evidence, to transform research into evidence use: https://TransformURE.wordpress.com

Anita Kothari is an Associate Professor in the School of Health Studies at the University of Western Ontario. Her research focuses on understanding how to best support the use of research and knowledge in healthcare decision-making; with a focus on integrated knowledge translation (i.e., research co-production) particularly in public health systems and services.

Nicholas Mays is Professor of Health Policy in the Department of Health Services Research and Policy at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). He also directs the Department of Health-funded Policy Innovation Research Unit and leads the evaluation of the integrated care and support Pioneer programme in England which aims to improve the coordination of the NHS with local authority-funded social care to improve users’ experience of care.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below

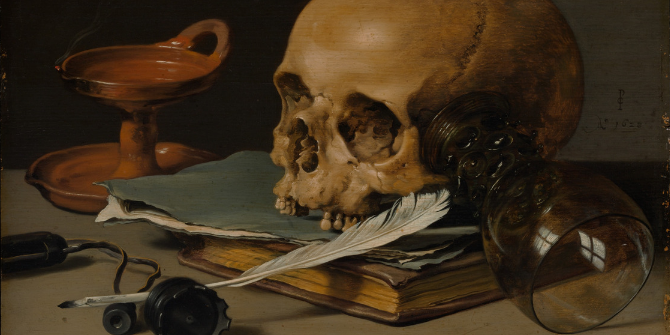

Image Credit, Freddie Collins via Unsplash (Licensed under a CC0 1.0 licence)

1 Comments