In Muddied Waters: The Fictionalisation of Ethnographic Film, Toni de Bromhead examines twelve documentary films about southern Italy to argue for a definition of ethnographic filmmaking as the ‘responsible and reliable’ gathering of footage through the avoidance of over-aestheticisation and other experimental aspects. While the book is of considerable disciplinary relevance and offers detailed and thought-provoking interrogations of the films under study, Sander Hölsgens suggests a less normative approach might allow researchers to explore a diversity of ethnographic sensibilities and practices.

This review originally appeared on LSE Review of Books. If you would like to contribute to the series, please contact the managing editor of LSE Review of Books, Dr Rosemary Deller, at lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk

Muddied Waters: The Fictionalisation of Ethnographic Film. Toni de Bromhead. Intervention Press. 2019.

In Muddied Waters: The Fictionalisation of Ethnographic Film, Toni de Bromhead sets out to reclaim a definition of ethnographic film that is on the brink of disappearing. Breaking away from the growing interest in merging the experimental with the ethnographic, de Bromhead measures twelve films against her own rules and regulations of ‘reliable’ ethnographic cinema.

In Muddied Waters: The Fictionalisation of Ethnographic Film, Toni de Bromhead sets out to reclaim a definition of ethnographic film that is on the brink of disappearing. Breaking away from the growing interest in merging the experimental with the ethnographic, de Bromhead measures twelve films against her own rules and regulations of ‘reliable’ ethnographic cinema.

‘Making an ethnographic film’, de Bromhead writes, ‘is about the responsible and reliable gathering of footage that, when edited into a film, should reveal something about a society and its people’ (16). For the British documentary filmmaker, this means avoiding any form of ‘aestheticisation’, the ‘over-use of close-ups’, montage, extra-diegetic music, nonlinearity and more generally all kinds of manipulation of the material that strengthen story or argument. A successful and reliable ethnographic film, it seems, should present itself au naturel.

De Bromhead’s benchmarks for ethnographic film are strict, yet not necessarily critical or tenable. If anything, they are ascetic: it’s not about the potential richness of using moving images during fieldwork, but rather about constraining one’s praxis and technological means to what’s indispensable to ‘reliably’ represent a culture or people. Everything else, the book suggests, is deceptive or at least problematic. Not only does such a formal rigour disregard the ethnographic qualities of recently produced pieces like Lucien Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s Leviathan (2012) and Yen-Ling Tsai, Isabelle Carbonell, Joelle Chevrier and Anna Tsing’s Golden Snail Opera (2016), but it also signifies a return to a discourse from the 1980s – before anthropology’s crisis of representation.

Specifically, Muddied Waters offers a disciplinary viewpoint that reminds me of many of the early critiques of Robert Gardner’s Forest of Bliss (1986) – an ethnographic film on religious practices in Varanasi, India, that decidedly steered away from context and language as dominant cultural signifiers. Rather than providing a thick description or mechanisms as simple as subtitles or voiceovers, Gardner embraced the aesthetic potential of analogue film and (non)diegetic sound to render (and, arguably, accentuate) the sensory experiences of everyday life. Colour, framing, sound design, montage and symbolism play an important part in the stories that Gardner tells, and his praxis was heavily criticised for being anything but ethnographic or anthropological. Nevertheless, Forest of Bliss proved to be a harbinger for more experimental approaches to ethnographic film and visual anthropology – a trend de Bromhead seems to denunciate in this monograph.

The assessments of the films themselves are engaging and thought-provoking. Muddied Waters’ geographic focal point – southern Italy – generates both a fascinating chronology of site-specific films and a critical account of regional histories. Tracing the ethnographic in a dozen films, de Bromhead starts out by discussing how Luchino Visconti’s 1948 fiction film La Terra Trema paves the way for representations of the ‘real’ and concludes with an insightful exposé of her most recent piece – A Wind of Change from 2019. In between, a range of documentary works are reviewed, specifically on the ethnographic merits of the filmmakers’ working methods.

Silvia Paggi’s Fils De Jambe Tordue (1994) is lauded for being the ‘purest ethnographic film in this selection’, as its ‘only aim is to carefully document an antique way of planting vines, picking grapes and making wine on the island of Salina, off Sicily. As such the narrative structure of the film is solely there to serve the ethnography, to give order and meaning to a process, without any conflict between narrative form and ethnography’ (139). One of the strengths of de Bromhead’s analysis lies in her extensive and meticulous reconstruction of some of the film’s scenes:

Grandad [sic] – the head of the family – is in a loggia working. There is a stack of large baskets. A man shouts:

– Granddad, can we go down now?

Cut to a boy with a barrow full of baskets going down the road. Granddad walks down the road, supporting himself with a stick. He calls:

– Let’s go

Boys pick up the baskets by the road, and men and women go down a narrow passageway that cuts through the house. They are all carrying baskets.

Cut to an establish shot (…) (143)

Despite a lack of still images, de Bromhead succeeds in vividly describing a few of the more pressing scenes of Fils De Jambe Tordue, highlighting Paggi’s working techniques and narrative strategies. What stands out, in this particular instance, is Paggi’s emphasis on the repetition and monotony of picking grapes. In so doing, Fils De Jambe Tordue explicates the rhythms and socialities of everyday labour – gesturing towards its traditional gender division and generational transmission of knowledge. In other words: as an ethnographic account, the film teases out the sociocultural context of grape picking and wine pressing on the island of Salina.

These in-depth descriptions of ethnographic and documentary films are all the more interesting because of de Bromhead’s geographic expertise: over the past couple of decades, she has made eight films on anti-Mafia activists in western Sicily, on top of multiple TV productions and visual studies on sociopolitical issues in the region. As such, Muddied Waters offers an inspiring study of films made in southern Italy, showcasing works from both local and international filmmakers. By providing critical details about the filmmakers’ education, the book also engages with different strands of anthropological and documentary education, from the more arts-oriented anthropology faculty at Goldsmiths to the alleged ‘openness’ of Manchester’s Granada Centre: at the latter department, for instance, Rossella Schillaci ‘was not taught a particular style, but was invited to consider which style might be most appropriate for any particular film’ (155).

This emphasis on more or less rigid ethnographic methods and styles – including what is appropriate or not – is emblematic of Muddied Waters. It aspires to provide a useful definition for ethnographic film, so as to ‘build up the common ground and understanding that provides a useful measure, as well as a clear means of communication in any debate on the subject, and in any experiments’ (14). While I recognise the disciplinary relevance of this endeavour, I do wonder what we could gain from a less normative approach – for instance, by focusing on a diversity of ethnographic sensibilities and practices. Perhaps this would allow us to move beyond binaries of form and content, the aesthetic and the reliable, direct representation and fiction.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

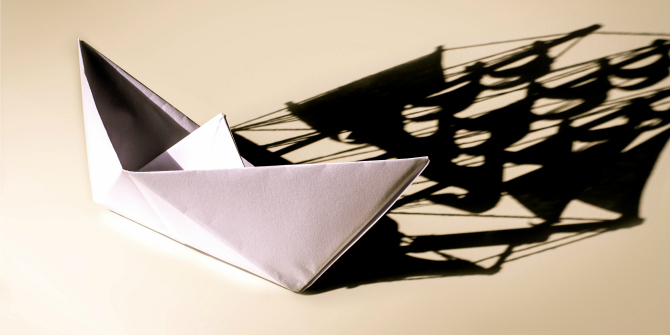

Image credit: Jakob Owens via Unsplash