Behind the finalised pages of any academic book lies a range of processes and contributions that led to its creation. Discussing her recent work Living Books, Janneke Adema explores how open online tools have given expression to these procedural aspects of academic book publishing and points to how they provide a space in which to re-consider long-held practices contributing to, and the uses of, the contemporary academic book.

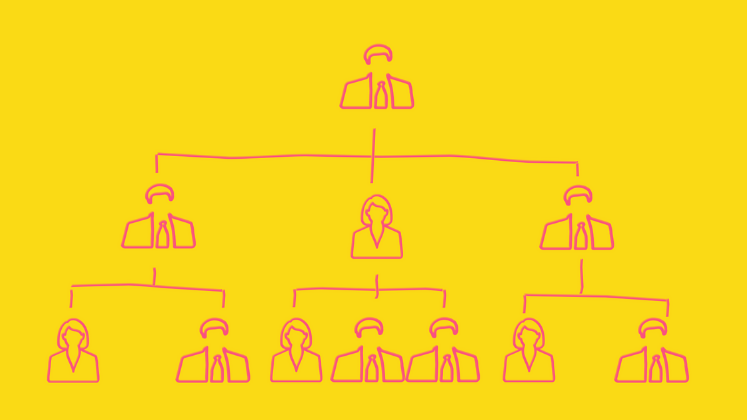

Despite developments in digital publishing, books in the humanities and social sciences are still predominantly produced as bound and fixed objects (published in print or PDF format) written by an individual author. Scholarly publishing workflows and business models, as well as academic assessment systems, are similarly mostly organised around the book as a discrete unit of scholarship, representing the final outcome of a research project.

In my recent book, Living Books: Experiments in the Posthumanities, I question this state of being by outlining how research and books have always been developed iteratively and collaboratively and how digital technologies offer opportunities to highlight the communal and processual nature of research more. Could this be the starting point for a different scholarly communication system, less focused on authors as brands and books as commodities?

Despite developments in digital publishing, books in the humanities and social sciences are still predominantly produced as bound and fixed objects (published in print or PDF format) written by an individual author.

In Living Books, I explore several pioneering book projects that have experimented with the idea of the processual book, incorporating practices such as reuse and remix, collaborative authorship, openness, community review and annotation, and versioning and updating. For example, McKenzie Wark’s GAM3R 7H30RY, created from 2006 onwards as a modular and networked book, was published serially online (GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1) while displaying a conversation between author and readers via online commenting in the margins. Comments where incorporated in a revised version 2.0, released as a print (version 2.1) and digital book, again open for discussions in the margins, and as a version 3 consisting of visualisations of the book’s contents.

Pushing these collaborative aspects even further, Open Humanities Press Living Books about Life series of twenty-five openly editable books, were made available on an open-source wiki platform, allowing for collective writing and open editing. These wiki books reused, repurposed, and connected previously published open access research materials (articles, books, images, videos etc,) and repackaged them in an openly updatable collection, to challenge the “physical and conceptual limitations” of the codex book.

Home Page of the Living Books about Life book series: https://www.livingbooksaboutlife.org/

In remixthebook Mark Amerika explored the potential of remix through collage-writing (based on a mash-up of other sources), while also creating a website with video, audio, and text-based remixes as an online companion to the printed book. Based on selected sample material, over 25 artists and theorists created multimedia writings that remixed and responded to texts from the print volume, opening the book and its source material up for continuous multimedia recutting while highlighting the communal aspect of creativity in art and academia.

Trailblazing were also Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s experiments with peer-to-peer review applied to the manuscripts of her books Planned Obsolescence and Generous Thinking. Fitzpatrick used the CommentPress WordPress plugin, which allows readers to comment in the margins of texts, to gather feedback on her manuscripts, which was then incorporated into the published versions. With this Fitzpatrick wanted to promote a more community-oriented system of quality control and forms of collaborative and networked writing, but also aimed to make visible the processes of scholarly research and publishing.

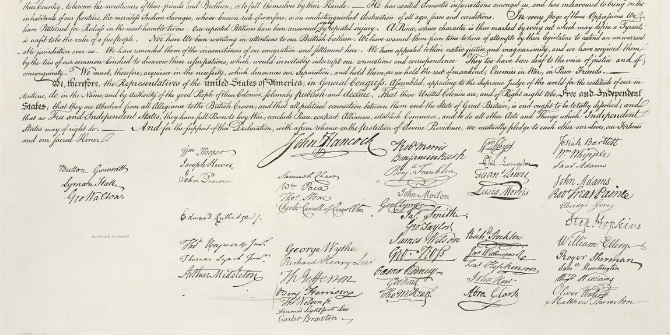

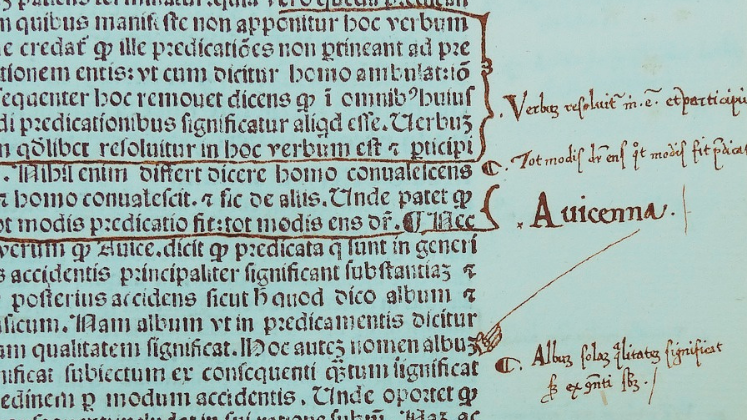

These book publishing experiments were groundbreaking in exploring how scholarly research can be networked online, how communities can be created around its various iterations, how existing open research can be reused and build upon, and how scholarship can be co-created in an ongoing manner. The collaborative and processual nature of research has always been visible in print-based forms of scholarship too (see academic referencing systems, papers and discussions at conferences, and revised and updated editions), but this has been further expanded in a digital environment: initially by making research ideas public through mailing lists and blogs, and more recently via social media, collaborative writing and publishing platforms, and online recorded talks at conferences.

The book publishing landscape was initially slow to adapt to these developing practices, but increasingly publishing infrastructures are accommodating the various processes through which book research can and is being made openly available online. From the development of tools for online annotating and commenting—including CommentPress and hypothes.is, which support community dialogue around publications—to publishing platforms that can incorporate resources and multimedia material (text, data, sound, video) while providing options to formally version, update, and revise works.

For example, PubPub is an open authoring and publishing platform which focuses on community publishing by integrating annotations and conversations as well as versioning, with digital scholarly publications. MIT Press have started to use PubPub to experiment with pre and post publication community peer review, conduct book sprints, and publish works in progress that can be further updated and versioned.

Making the processual nature of books and research more visible, triggers some fundamental questions about how scholarly publishing is set up

Another open-source solution, the Manifold platform, allows authors to add multimedia materials and datasets to a publication as it develops or is iteratively published. The University of Minnesota Press is using Manifold to publish their Forerunners series of short books that serve as pre-releases of larger books-in-development. These ‘forerunners’ are seen as ‘grey publications,’ or ideas-in-progress, showcasing how research material publicly ‘evolves over time’, data and comments are incorporated, and revisions are made.

Making the processual nature of books and research more visible, triggers some fundamental questions about how scholarly publishing is set up, which might prompt scholars and publishers to re-evaluate how and why research is currently being made public, at what stages and for which reasons (from collaboration to assessment and career progression)? How are these various versions bound together again to create something that constitutes, perhaps, a book? And how is engagement created around these different iterations (given how it is formally set up around established forms such as conference papers and book releases)?

Processual books can, for example, make the various contributors to scholarly research more visible and the different ways they shape research as it comes into being. They can also highlight the material agency of publications and how it matters whether research is published as a blogpost or an academic monograph, openly or closed, and how different media and the various cultural practices established around them enact different forms of interaction and call into being different communities of engagement.

When boundaries between research and publishing become less clear-cut, this has direct implications for the role of the publisher too. Instead of publishing being ‘outsourced’ to a publisher when a research project ends, processual publishing might ask authors and publishers to collaborate more and earlier in the research cycle and to reconsider at what point publishing expertise (e.g., reviewing, copy-editing, marketing) is most useful. Yet processual publishing practices also make visible how scholars are increasingly taking on publishing functions, having to present themselves as ‘academic brands’ online and through their academic networks to create engagement around their work. Many of the platforms that scholars publish their research-in-progress on (including academic social networking sites such as Academia.edu) are also extractive, building their business models around this engagement.

Processual publishing will continue to be faced with these kinds of questions and new forms of extraction and solidification (around the claiming of ownership, the creation of marketable commodities, and the metrification of engagement) will continue to be introduced as these practices become more widespread. But remaining aware of when and for what reason research is made public might help scholars and publishers make more informed publishing decisions and might help them envision and create a different—and perhaps better—scholarly communication system.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Pawel Czerwinski via Unsplash.

2 Comments