As Twitter moves to become a private company owned by the billionaire Elon Musk, Mark Carrigan, reflects on the increasing importance academic social media and academic twitter has secured in universities for building academic communities and for public engagement and impact. Assessing what the acquisition might mean in terms of relations on the platform, he argues universities should more carefully consider how they engage with social media platforms to achieve these aims.

I have seen a great deal of anxiety in recent days about Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter. These concerns reveal pre-existing anxieties about the microblogging service, which over the last decade has grown from a marginal feature of academic life into something many universities tacitly expect of their staff. What was once a subversive and energetic space outside of the university system, is now a routine part of it, with follower counts being treated as proxies for research impact capacity and engagement metrics featuring in impact case studies. This isn’t the reason most academics use Twitter, but the subtly violent manner in which it hybridises the personal and the professional leaves many academics with an ambivalent relationship to it. In this sense, the unexpected shock of the world’s richest man buying a platform that is, amongst many other things, a central communications infrastructure for academics, might lead academics to reflect on how we relate to the platform.

It might be many months until the direction of travel, best-case reversion, or worse-case dystopia, is discernible. Yet, the current reconsideration of Twitter by academics and what it suggests about digital scholarship is significant.

The media analyst Charlie Warzel helpfully outlines three likely scenarios for Musk’s takeover. The best-case scenario is a reversion to the recent past, with Twitter coming to look more like it did before the introduction of a range of tools designed to mitigate previously unchecked harassment. As Warzel reminds us, it “was often an awful place, especially if you were a woman, Jewish, a person of color, or a member of any minority group”. The worst-case scenario would be one in which Musk seeks to turn his new plaything into something akin to platforms like Gab, Parler or Truth Social. This might involve reinstating high profile banned accounts under the sign of ‘free speech’, as well as defunding moderation and safety features. As Warzel makes clear, it’s not beyond the realms of possibility that he runs the platform “in a truly vengeful, dictatorial way, which involves Musk outright using Twitter as a political tool to promote extreme right-wing agendas and to punish what he calls brain-poisoned liberals”. The manner in which an Indian-born female Twitter executive received online abuse following a tweet from Musk provides a worrying sign of what this might look like in practice.

It might be many months until the direction of travel, best-case reversion, or worse-case dystopia, is discernible. Yet, the current reconsideration of Twitter by academics and what it suggests about digital scholarship is significant. There is a reflexive moment happening within British higher education, driven by a number of interrelated factors (transition from emergency remote teaching to hybrid delivery, an intractable labour dispute and a rapidly mounting cost of living crisis). How we use social media matters, because it has become the main way we converse with others outside of our institutional milieu, including how we respond collectively to these challenges.

In the last week I have had numerous conversations with academics about what it is like to delete your Twitter account. If you’re considering this possibility, then it’s hard to avoid thinking about the time and energy you have put into Twitter, as well as what it means to jettison this permanently. Seen through a sociological lens there’s an element of the Ponzi scheme about the professional use of social networks by academics. The followers you’ve accumulated through your use of the platform only retain their value if these people continue to log in on a regular basis. If social media popularity is to have any currency as academic capital (and it does, even if the dynamics of convertibility remain unpredictable) then the platform on which you are popular needs to be perceived as current and relevant. It might seem cynical to view it in these terms, but I’d argue it’s important we recognise how Twitter has become a forum in which we increase visibility, find opportunities and identify connections in a way which is a core part of our wider professional life. We need to recognise that Twitter has become part of higher education, at least in the UK, rather than being a subversive hinterland outside of universities.

One response to these developments has been to jump to the idea of an alternative, whether that is a commercial platform with their own baggage, such as LinkedIn or Facebook, closed platforms such as Slack or Discord, or smaller open platforms such as Humanities Commons or Mastodon. While not denying the value of social platforms outside the circuits of capital accumulation, I worry that a rush towards alternatives might fracture the professional networks that make Twitter valuable in the first place. Furthermore, the assumption there is one alternative for academics, fails to grapple with the peculiar way in which academics have used Twitter for two distinct purposes: building research communities and public engagement.

It might seem cynical to view it in these terms, but I’d argue it’s important we recognise how Twitter has become a forum in which we increase visibility, find opportunities and identify connections in a way which is a core part of our wider professional life.

There’s little need for open networks to build research communities and collaboration platforms like Slack, Discord or Teams, could come to constitute a more powerful version of the Listserv. What is important is that they are managed in a way which avoids a retreat into pre-existing closed professional networks. During the pandemic there has been a huge growth in small collaboration networks using platforms like this, with varying levels of activity, to loosely work together at a distance. Perhaps it’s time for us to think more systematically about how we should utilise these platforms, as well as discuss what it means to use them well or badly.

In contrast, public engagement through digital platforms is in some ways a more specialised endeavour, in so far that it is harder to do right and there are more things which can go wrong. If universities and funders want to build a culture of engagement then it’s important they invest in the infrastructure needed to do this well, rather than relying on individual activity in a way which fails to grasp the complex attention economy of a platform like Twitter. This might be a renewed investment in group blogging infrastructure to ensure that academics have a practical means to make their expertise available to stakeholders outside the academy on an opt-in basis, without the messy and risk laden work of maintaining a public profile on Twitter. It could also be an investment in the rich and vibrant field of academic podcasting, which is now more mainstream than ever but needs careful cultivation if it’s to be able to reach its potential in terms of external engagement.

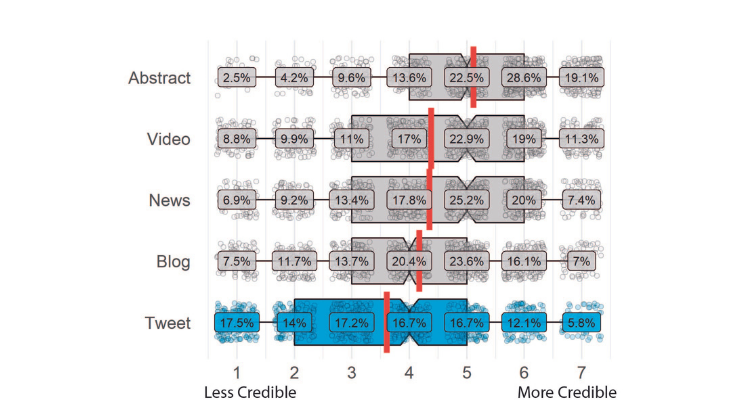

There are professional rewards to be realised through the use of Twitter, such as increased readership, fruitful collaborations and research impact. Katy Jordan and I have argued that it’s the perceived value for impact and engagement, which most explains the encouragement of social media use by university management. The reason for the spiralling Equality, Diversity and Inclusion issues which Twitter has generated comes, because these rewards are not distributed equally. As the sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom put it, “all press is good press for academic microcelebrities if their social locations conform to racist and sexist norms of who should be expert”. In contrast, if you’re not a white middle class male intellectual, who conforms to those norms, you’re likely to confront a radically different social media, where your expertise might be questioned, you might be personally attacked and subject to hateful abuse in a swarming process of “networked harassment”.

As Cottom goes on to say, “the risk and rewards of presenting oneself … are not the same for all academics in the neo-liberal ‘public’ square of private media”. Not only are universities marching their staff out into this public sphere under the sign of impact, in many cases they’re also blaming them if things go wrong. This becomes truly egregious given the substantial evidence base we now have about the relationship between gender and race (in particular) and the likelihood of being subject to online abuse. If even the best-case scenario for Twitter post-Musk comes to pass, then these challenges are only going to grow. This suggests university management should stop perceiving social media as a black box for generating public engagement and instead put in place policies and procedures that are adequate to the real and significant risks digital public engagement poses for academics.

It remains to be seen what Twitter will be like after (and if) Musk takes control. The sense of risk and questions it poses, nonetheless invite us to think much more seriously about the infrastructure we rely on for digital scholarship. I would argue this means no longer seeing digital public engagement through the lens of individual users and instead finding ways to approach it as networks, communities and organisations, with an interest in how academic knowledge circulates within universities and beyond them.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: mohamed_hassan via Pixabay.

5 Comments