Drawing on her book, Cut/Copy/Paste, Whitney Trettien reflects on the history of radical bookwork and what it can teach us about digital publishing today. (This feature essay first appeared on the LSE Review of Books Blog).

John Mansir Wing (1844-1917) was something of a character. A printer, typesetter, publisher and newspaper reporter, he retired early in Chicago at 44 and dedicated the rest of his life to collecting and – more unusually – extra-illustrating books: that is, inserting images to create bespoke copies.

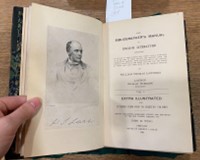

Wing was charmingly serious about this pastime. At home, he dedicated a room that he called ‘The Old Corner Library’ to his books. Later, he moved to an office at the Newberry Library that he dubbed ‘the cloister’. In these book laboratories, surrounded by pots of glue, sharpened knives, scissors, loose sheets and huge piles of prints – so many that he bought them by the pound – he cut up the bindings of his favourite books and stuffed them with illustrations. Some of the engravings and woodcuts he used were old and rare; others were ephemera like menus, letters, or advertisements cut from popular magazines. Jill Gage, curator at the Newberry and the scholar who has done the most research on Wing’s remarkable collections, even found one book padded with an entire 1910 Marshall Field’s hosiery catalogue – essentially, junk mail. As if to emphasise the seriousness of his project, Wing had new title pages and sometimes new prefaces written and printed for the books he extra-illustrated, adding his name in the same typeface and size as the author’s: ‘prints collected, arranged, inlaid and mounted at the Old Corner Library by John M. Wing.’

Wing was charmingly serious about this pastime. At home, he dedicated a room that he called ‘The Old Corner Library’ to his books. Later, he moved to an office at the Newberry Library that he dubbed ‘the cloister’. In these book laboratories, surrounded by pots of glue, sharpened knives, scissors, loose sheets and huge piles of prints – so many that he bought them by the pound – he cut up the bindings of his favourite books and stuffed them with illustrations. Some of the engravings and woodcuts he used were old and rare; others were ephemera like menus, letters, or advertisements cut from popular magazines. Jill Gage, curator at the Newberry and the scholar who has done the most research on Wing’s remarkable collections, even found one book padded with an entire 1910 Marshall Field’s hosiery catalogue – essentially, junk mail. As if to emphasise the seriousness of his project, Wing had new title pages and sometimes new prefaces written and printed for the books he extra-illustrated, adding his name in the same typeface and size as the author’s: ‘prints collected, arranged, inlaid and mounted at the Old Corner Library by John M. Wing.’

In the long history of publishing, what are books like these, assembled entirely from found materials? Have the original copies simply been modified by Wing? When do these modifications become so extreme as to constitute an entirely new publication, a handmade edition of one? And what do we call someone who does not write books like an author but instead cuts, pastes and compiles them? These are the questions I explore in Cut/Copy/Paste, a book about the history of radical bookwork, as I call these types of practices, and what it can teach us about digital publishing today.

While Wing was working in the modern era, in Cut/Copy/Paste I spotlight the seventeenth century, a moment ripe with experimentation in the history of the book. By this time, England had become accustomed to movable type as a technology: presses and a guild had been established, literacy rates were increasing and readers had developed durable practices for managing information overload, like commonplacing. As print became a more accessible and standard feature of the media environment, readers began exploring new ways of assembling texts and images that reflected their changing attitudes across a century of social upheaval.

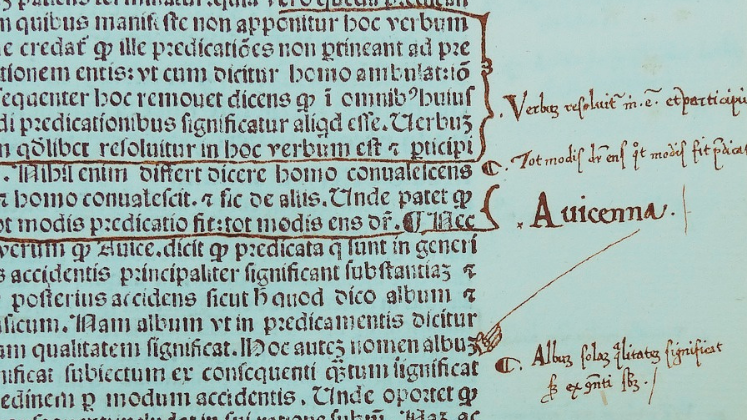

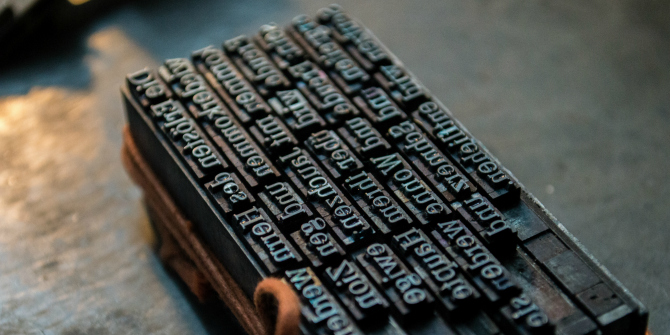

I look at three communities in particular where readers compiled bespoke books from found fragments: a religious household where the women of the family cut and paste together illustrated bibles; a queer partnership that published multimedia books of poetry; and a shoemaker-turned-book agent who assembled albums that narrate the history of the book from what was essentially trash. In each case study, we find dedicated booklovers like Wing making their own inventive contribution to the history of publishing.

While the stories I tell in the book originate in the seventeenth century, their lessons are not confined to the early modern period. As Wing’s collection of extra-illustrated books shows us, experimental publishing can be found wherever there are readers with scissors, paste and access to printed materials. This, of course, includes today. As our reading and writing move from printed paper to tiny simulation keyboards, ‘cutting’ and ‘pasting’ have become taps and commands, often on platforms that bake these actions into their features. After all, what is a retweet but someone else’s text that we have copied and pasted onto our own timeline?

While the stories I tell in the book originate in the seventeenth century, their lessons are not confined to the early modern period. As Wing’s collection of extra-illustrated books shows us, experimental publishing can be found wherever there are readers with scissors, paste and access to printed materials. This, of course, includes today. As our reading and writing move from printed paper to tiny simulation keyboards, ‘cutting’ and ‘pasting’ have become taps and commands, often on platforms that bake these actions into their features. After all, what is a retweet but someone else’s text that we have copied and pasted onto our own timeline?

Throughout Cut/Copy/Paste, I keep an eye to our digital practices, especially emerging forms of publishing on the web, and point to the many ways this deep history of experimental bookmaking might inform our changing understanding of creativity, authorship and publishing today. This presentism is not anachronistic so much as necessary in an era where the hype of technological novelty often overshadows the lessons of the past.

It is difficult to spend so much time researching creative approaches to publishing and not want to put the same ideas into action in your own book – and so Cut/Copy/Paste has a second life as a networked digital text. While one can certainly buy the print version and read it without ever opening an internet browser, it is also possible to access the same text for free on University of Minnesota’s instance of the Manifold platform. Many passages of the digital book have been linked to an array of assets and resources: images and videos of the books I discuss, datasets about historical collections, visualisations, maps, social networks and digital editions. While I expect most scholars still prefer to read print, it was my aim to show that digital publishing not only is very possible today but can also be transformative for the kind of stories we tell, as I argue in the introduction. Like Wing’s extra-illustrated books, the digital version – ‘collected, arranged, inlaid and mounted’ by myself – offers a richly multimodal variant on the same text: a playground for new experimentation.

It is difficult to spend so much time researching creative approaches to publishing and not want to put the same ideas into action in your own book – and so Cut/Copy/Paste has a second life as a networked digital text. While one can certainly buy the print version and read it without ever opening an internet browser, it is also possible to access the same text for free on University of Minnesota’s instance of the Manifold platform. Many passages of the digital book have been linked to an array of assets and resources: images and videos of the books I discuss, datasets about historical collections, visualisations, maps, social networks and digital editions. While I expect most scholars still prefer to read print, it was my aim to show that digital publishing not only is very possible today but can also be transformative for the kind of stories we tell, as I argue in the introduction. Like Wing’s extra-illustrated books, the digital version – ‘collected, arranged, inlaid and mounted’ by myself – offers a richly multimodal variant on the same text: a playground for new experimentation.

Further reading:

Jill Gage, ‘With Deft Knife and Paste: The Extra-Illustrated Books of John M. Wing,’ RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 9.1 (2008), 118-26.

Lucy Peltz, Facing the Text: Extra-Illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain 1769-1840 (Huntington Library, 2017).

Image 1 Credit: New title page that John Wing had printed and bound in a copy of William Lowndes’ The Bibliographer’s Manual of English Literature, naming himself as the book’s extra-illustrator. From the collection of Wing’s extra-illustrated books at the Newberry Library. Photograph by the author.

Image 2 Credit: A page opening from the King’s Harmony, a new bible that the members of the religious household of Little Gidding made circa 1635 for King Charles by cutting and pasting together printed bibles and religious engravings. British Library, C.23.e.4, cols. 37–40.

Image 3 Credit: An arrangement of title pages in one of John Bagford’s albums of specimens, which he collected at the end of the seventeenth century. British Library, MS Harley 5927, for. 7r.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Joanna Kosinska via Unsplash.

Fascinating, look fwd to reading it – just wondering if you have come across the “scissors and paste” method of Sima Guang in Tang Dynasty China, which was around the time the first printing presses were used in China.

This URl https://tinyurl.com/dzmmand7 should hopefully direct you to the passage in La Fleur, R. A. (1999). Literary borrowing and historical compilation in medieval China. In, L. Buranen & A.M. Roy (Eds.) Perspectives on Plagiarism and Intellectual Property in a Postmodern World (pp. 141-150). New York: SUNY Press.