The phenomenon of predatory publishing is well known following the work of Jeffrey Beall and others in highlighting and popularising the issue. In a new book titled The Predator Effect, Simon Linacre draws on his experience in tackling deceptive publishing practices, and urges the scholarly communications industry to focus, less on predatory publishing as a theoretical issue and more on the real world negative impacts that can be caused by predatory journals.

What’s in a name? When I decided to write a book about predatory journals in early 2021, almost the first choice I made was to call it ‘The Predator Effect’. After working in academic publishing for the best part of 20 years and aware of the predatory publishing phenomenon for most of that time, I knew the problem had been mired in hair-splitting definitions and arguments around subjective criteria. It was time to understand the real impact of predatory publishing practices.

But first, the definition of what predatory publishing actually means has to be tackled. This is where some of the controversy around predatory publishing had arisen in the past, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, when Jeffrey Beall coined the phrase in 2010, he didn’t really define them as such, merely highlighted the scam of journals asking authors to pay an article processing charge (APC) for sub-standard publishing. He used the term ‘potential, possible, or probable predatory scholarly open-access publishers’ on his now-defunct website that contained ‘Beall’s List’, but this circular description isn’t really helpful either.

A more successful attempt to define predatory practices was made in 2019 by Grudniewicz et al as:

“entities that prioritize self-interest at the expense of scholarship and are characterized by false or misleading information, deviation from best editorial and publication practices, a lack of transparency, and/or the use of aggressive and indiscriminate solicitation practices.”

This definition led Prof Björn Brembs to the conclusion that the world’s largest publisher Elsevier could also be defined as a predatory publisher.

The problem that predatory journals present has been similarly dismissed in the past, on the grounds that some studies on predatory publishing have been flawed, there are bigger fish to fry in academic publishing practices, and that education of authors would provide an answer. And yet the problem persists with well over 16,000 journals now listed on Cabells’ Predatory Reports database, and education still has some way to go with the recent study from India that showed 41% of academic authors surveyed were not aware of predatory journals.

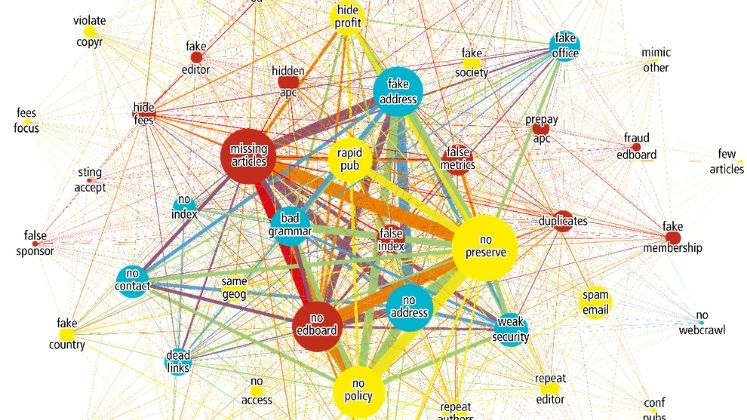

Defining or measuring the problem is inherently difficult given the shady nature of predatory publishing practices, and this has led others to conclude that it is better to understand the spectrum of activities encompassed by predatory publishing, rather than get hung up on definitions. There is some sense in this, and indeed part of the scope of my book is to contextualise where the phenomenon came from and the variety of ways it has manifested itself. But the academic community and other stakeholders in scholarly communications will need more clarity to successfully avoid both publishing and reading predatory journal content.

One stakeholder that evidently did think predatory journals are a major problem is the Federal Trade Commission in the US which found in 2019 that publisher OMICS International was guilty of defrauding authors paying to publish articles in hundreds of its journals, issuing a fine of just over $50m. The fact that this represents a small percentage of all the APCs that have been paid over the years by authors to predatory publishers – in return for a pdf on a website that hardly anyone will find and even fewer will read or cite – this in itself suggest that the impact of predatory journals has at least seen millions of dollars of funders’, universities’ and authors’ money be wasted.

The problem has also led to the skewing of academic behaviour, especially where predatory journals have found their way into official lists of journals where authors are encouraged to publish. Add to this the personal problems encountered by authors unwittingly sucked into the traps laid by predatory publishers – which now extend to books, conferences and virtual events – then it’s undeniable the impact of predatory behaviour has an impact on academia and the dissemination of knowledge.

However, perhaps the real ‘predator effect’ is the risk society at large is exposed to where journals purporting to be scholarly and peer reviewed instead present articles that have not been validated and contain disinformation or ‘junk science’. In a yet-to-be-published study conducted on a tranche of predatory journals that had published articles relating to COVID-19, it was found that:

- Most articles reported preventive methods to control COVID infection, models to predict infection spread or drugs and vaccines to prevent the spread of the virus or treatments for COVID-19

- Studies reporting the successful use of Hydroxychloroquine, Chloroquine, Ivermectin and treatments such as convalescent plasma therapy – or other complementary medicinal therapies with no clinical trials and small sample sizes – were also found

- Within a short timeframe 85% of predatory articles we investigated received at least a single citation, which is much higher than previous studies have shown.

Similar issues have been highlighted where experimentation on people and animals has been published without any of the usual integrity checks reported. It is in this area where the impact of predatory publishing is perhaps clearest, with articles published in predatory journals also pushing conspiracy theory claims such as 5G masts causing people to catch COVID -19. These can be read, reported on and amplified by the media, significantly contributing to the ‘infodemic’ of recent times. As such, while the problem of predatory publishing can often seem remote or difficult to quantify, the effect of predatory practices can be very real indeed.

Conflict of Interest Statement: I worked for Cabells as Marketing Director from Aug 2018-Jul 2022

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Alfred Kenneally via Unsplash.

From the scholar side of things, I think most of the people I know in the majority anglophone and francophone world would never publish in a dodgy predatory outlet ever, and know the signs. It is first time time-poor or authors that may get caught out, but probably only once. I have produced this guide to free or low cost decent journals in several fields to help. https://simonbatterbury.wordpress.com/2015/10/25/list-of-decent-open-access-journals/ But as somebody, cannot remember who, pointed out, the situation in some countries is very different, and it is possible to secure an academic post and get promoted with publications in journals that in the west may be considered ‘predatory’. The point is that if we actually read the work, we can often be surprised: there are gems even in some terrible journals. Not to condone low standard journals that will publish your paper after providing fake referee reports and charging you a $100 APC. But whole point of the DORA declaration is to get us to consider quality separate from outlet, after all. Beall never believed that. Personally, like Björn Brembs, I am more interested in tackling the business practices of the big fish, which take $3000 APCs from us …for what? For an article that in the ‘artisanal’ diamond OA sector, we would publish without charging you anything.

I have recently co-authored a paper on COVID-19-related research in predatory journals where 16% of corresponding authors were based in the US. I do not think this is an issue anglophones can feel complacent about, or patronise the non-English speaking world about.

Also complicating is that if one were to sit down with one of these predatory journals, they’d likely find that they aren’t nefarious or ill-intended at all, and that they insist they do not publish dodgy material, and can convincingly back that up and justify their legitimacy in most cases. They are merely perceived as incompatible with our particular social narrative, and thus condemnable. I think we get a feeling of dissonance when we see information that we perceive as in conflict with what we already believe… presuming that both cases cannot be true. But they often can and are, we just don’t immediately know how they can coexist, and to get there we would have to face some effort and perhaps significant discomfort. Further complication arises when we fear that accepting or considering certain information will alter one’s social identity, making them appear sympathetic to some out-group. This is, of course, the opposite of objective analysis and reasoning, since it is governed by emotion and social dynamics.

This is demonstrably not true. If you look at the Cabells Predatory Reports criteria for including journals in its database, they are designed to only include journals that would not pass this sort of test, ie. on the journal sites they are deceiving authors by saying they are doing peer review (they are not), are widely cited (they are not) or have an Impact Factor (they do not). There are a number of journals that one might say are incompetent or poor, but these are not predatory journals.

As an indigent, non-university-attached PhD researcher in a third-world context, I have of course already been predated by the highly priced respectable journal industry. I cannot afford to make a contribution any more. Everybody wants money from me to publish, so I experience the entire Journal Industry as predatory. I was publishing under Academia, but then they got enough momentum to be able to charge university rates for publishing. I am currently half-heartedly searching for a reputable free-to-publish platform that might give my ideas some sort of platform, but I have been discouraged by recent experiences.

I know the system was designed to deny a platform to tinfoil-hat authors. But it also combs out authors like me 🙁 You can check me out on Academia – they still carry my articles that were part of their build up to profitability 😀

Please consider the green open access route to publish – post your working paper on a relevant subject-based repository for no charge, and submit the paper to a subscription journal. You can still share your work via the repository, and hopefully gain validation if it is accepted by a journal.