Reflecting on nearly twenty years of transdisciplinary practice and research and the recent publication of their new book, New Mediums, Better Messages? How Innovations in Translation, Engagement, and Advocacy are Changing International Development, David Lewis, Dennis Rodgers and Michael Woolcock consider how the role of popular and vernacular knowledge is essential to international development.

Launched two decades ago, our ‘Popular Representations of Development’ project began with the premise that the arts were an overlooked and underappreciated source of legitimate knowledge about international development in all its many facets – from the drivers of disadvantage, inequality and dislocation to the pathways through which steps to a better life can be articulated, forged or denied.

Consider a simple thought experiment: if one’s reading material was restricted exclusively to the Quarterly Journal of Economics, what would one conclude about the nature of global poverty and the best ways for societies to respond? It surely goes without saying that this ‘diet’ would be regarded by most people as ‘unbalanced’. But, what if that diet was limited solely to shiny policy reports from the United Nations Development Programme? A similar conclusion, perhaps, with a concession that more attractive graphics improved the content, and a section on ‘policy implications’ increased the relevance.

if one’s reading material was restricted exclusively to the Quarterly Journal of Economics, what would one conclude about the nature of global poverty and the best ways for societies to respond?

What about a menu comprising just novels, popular films, and music? Well, such material also has its own strengths and weaknesses… except that it also happens to have an audience of hundreds of millions of people – something that neither academic, nor policy outputs, can claim to have… Thinking even more broadly, what if the billions of poor people who are the central concern of international development were given a platform to share their views of their world, using whatever language and communicative modalities were best for them? What kind of stories would they tell, and how would this impact on (our) understandings of the world?

At a recent event at LSE, where we launched our new open access book on this topic entitled New Mediums, Better Messages? How Innovations in Translation, Engagement, and Advocacy are Changing International Development, we framed a discussion of these questions by asking ‘Is development an art or a science?’ The arts and sciences were intimately involved from the outset in development deliberations, policies, and justifications. The ‘romantic revolution’ in poetry and literature was an explicit critique and mournful lament of modernity’s insidious corrosion of long-established social mores, dignity, livelihoods, and separation from nature, as Tim Blanning has argued. Dickens and Elliot (among many others) wrote famous novels graphically depicting the wretched plight of the urban poor and the processes creating it. Historian Lynn Hunt goes so far as to argue that novels themselves played a decisive causal role in ‘inventing’ human rights. Indeed, it is fair to say that during the late 18th and 19th centuries, with the rapid spread of literacy beyond the confines of a small elite in most Western European and North American societies, novels and other works of fiction became one of the primary sources of information about the world beyond their immediate surroundings for a majority of people.

At a recent event at LSE, where we launched our new open access book on this topic entitled New Mediums, Better Messages? How Innovations in Translation, Engagement, and Advocacy are Changing International Development, we framed a discussion of these questions by asking ‘Is development an art or a science?’ The arts and sciences were intimately involved from the outset in development deliberations, policies, and justifications. The ‘romantic revolution’ in poetry and literature was an explicit critique and mournful lament of modernity’s insidious corrosion of long-established social mores, dignity, livelihoods, and separation from nature, as Tim Blanning has argued. Dickens and Elliot (among many others) wrote famous novels graphically depicting the wretched plight of the urban poor and the processes creating it. Historian Lynn Hunt goes so far as to argue that novels themselves played a decisive causal role in ‘inventing’ human rights. Indeed, it is fair to say that during the late 18th and 19th centuries, with the rapid spread of literacy beyond the confines of a small elite in most Western European and North American societies, novels and other works of fiction became one of the primary sources of information about the world beyond their immediate surroundings for a majority of people.

Yet today most development academics, practitioners, and policymakers largely discount the informative pretentions of the arts, despite mainstream discourse being replete with aphorisms conveying the virtues of ‘inclusion’, ‘equity’, ‘accountability’, that ‘one size doesn’t fit all’, ‘context matters’, and we should ‘leave no-one behind’. If we ignore the arts, might we actually impoverish our thinking about development? Certain dominant modes of articulating, reasoning, measuring, and inferring have come to determine – and perhaps limit – ‘what counts as a question and what counts as an answer’ in development debates. Might this have created an intellectual ‘monopoly’ – with all the attendant ‘inefficiencies’ and ‘distortions’ we associate with monopolies elsewhere? Might we reach different, and potentially more informed, conclusions and implications about development if our epistemological ‘diet’ was more diverse?

A wide range of innovative work at the interface between arts and humanities and development is now taking place. For example, since 2017, storytelling, music, theatre and other forms of art are central to ongoing efforts to manage environmental resources and protect populations against climate change in the Sundarbans area of India and Bangladesh, the world’s largest contiguous mangrove swamp now threatened by encroaching salinity and illegal logging.

Our point here is not to claim that inflation can be curbed by poets, or that a census and a novel are interchangeable as the basis for designing social policies, but rather that the very complexity of these global issues demands that we incorporate a corresponding array of authoritative sources of different kinds of knowledge, different kinds of ‘ordering’, and different kinds of expertise to create and protect the deliberative spaces within which these differences can be sufficiently accommodated.

Our point here is not to claim that inflation can be curbed by poets, or that a census and a novel are interchangeable as the basis for designing social policies

Anthropologist James Scott makes a distinction between ‘vernacular’ and ‘official’ orders, between ways of knowing based on local experience and lived point of view, and those based on abstract understanding and often with a particular purpose in mind. Building on this distinction, we can add two other forms of knowledge order. The first is ‘academic’, a mode of reasoning familiar to people who hold advanced degrees, organized into different disciplines, trained in how to speak with each other, their immediate colleagues and collaborators, and if they try really hard, perhaps a few others in adjacent fields. True experts complicate what everyone else thinks is simple because, in fact, most things in life – from digestion to parenting to taxation to diplomacy – are deeply complex. The second is ‘popular’ knowledge: broadly shared, widely communicated and easily commodified.

Creating and sustaining deliberative spaces within which these four contending ‘orders’ can engage meaningfully one another will require all parties to be willing and able to engage in ‘hard conversations’, which in turn will require hard work and sustained effort. In the 2020s and beyond, the interaction between orders in an increasingly interconnected world is likely to become more frequent, intense, contentious… and thus necessary.

All too often science necessarily does its work by attempting to simplify a complex reality, as in the case of environmental or economic modelling. By contrast, the best art is necessarily expansive in its scope and in the questions that it tries to ask. Can we somehow achieve the best of both worlds?

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

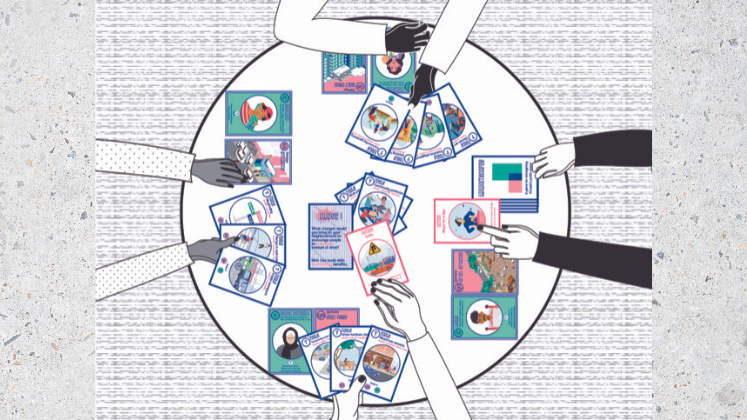

Image Credit: Adapted from Mapping exercise in Mtandire, Malawi, Slum Dwellers International (CC BY 2.0)