Historically, there has been a tight link between journals, journal publications and a community of scholars working in specific fields of research who contribute to and manage them. As journal publishing has become a global undertaking and moreover, an undertaking that is increasingly mediated through online digital interactions, Aileen Fyfe asks, do we need to rethink the structure of the learned societies that underpins them?

It has been almost a decade since I began thinking about academic publishing and learned societies. My team and I spent four years digging through the minute books, correspondence and reports held in the archives of the Royal Society of London, and almost as long again processing, analysing, writing and revising our history of scientific journals. The book is out at last, and now there is some space to reflect.

We originally set out to investigate the history of scientific journal publishing, but, immersed in the archive and history of the Royal Society, we couldn’t help noticing the changing relationship between journals and learned societies more generally.

Most often, when I’m asked about learned societies and journals, the context is economic. It’s easy to see why, as many society treasurers or journal directors are currently worried about the likelihood of journal publishing being a source of income for societies in the future. For those people, our historical findings are, perhaps, not initially reassuring. It’s clear that, for most of their history, scholarly research journals have not been money-making enterprises. As one commentator in 1895 put it, the publishing expenses for research papers are ‘in very many cases, very heavy’ but ‘the public which buys any particular scientific publication is very limited’. (Lord Rayleigh, secretary to the Royal Society, writing to HM Treasury; see Fyfe 2015 and 2022)

Some magazines with a more newsy approach to science have found enough paying customers to cover their expenses, but research journals in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries depended upon subsidies from learned society members, royal patrons, wealthy donors or, more recently, industrial sponsors and research funding agencies. It was only in the 1950s and 1960s that the development of an international market of library subscribers made it possible for research journals to find enough paying customers to cover their expenses, let alone to generate net income. But, the ability of library budgets to support the growing number of increasingly expensive journals was short-lived, as the Royal Society subscription numbers in Figure 1 demonstrate.

Fig 1. Commercial circulation of the Proceedings and Transactions, 1935–2010 (Source Fyfe et al. 2022, Fig.3)

Fig 1. Commercial circulation of the Proceedings and Transactions, 1935–2010 (Source Fyfe et al. 2022, Fig.3)

In historical terms, the profitability of research journals in the third quarter of the twentieth century appears as little more than a blip. In the long period before library subscriptions, journals were sustained by building a portfolio of multiple smaller income streams to support the cost of journal publishing. Similar approaches are being used in the transition to open access publishing.

It’s important to realise that the older approach to journal sustainability was grounded in a non-commercial understanding of ‘circulation’. The circulation and dissemination of their journals did matter to learned societies and academies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but not for financial reasons. The Royal Society gave free copies of its journals to its fellows, to the libraries of other learned societies, to the libraries of universities, and to a variety of learned institutions across Britain, Europe and (some of) the rest of the world (Fig.2). This was a practical way of ensuring that its journals reached the scholars, and scholarly communities, most likely to be interested. Some organisations reciprocated, sending their own journals to the Royal Society’s library. But, it was not cost-neutral. An internal review in 1954 revealed that the Society spent around £3,300 each year on the production and shipping of these copies, and only received around £900-worth of journals for its own library in return.

Fig.2 Global distribution of free copies of the Transactions and/or the Proceedings in 1908. The size of the spots is proportional to the number of copies sent to a given city (Source Fyfe et al. 2022, Figure 12.1)

Fig.2 Global distribution of free copies of the Transactions and/or the Proceedings in 1908. The size of the spots is proportional to the number of copies sent to a given city (Source Fyfe et al. 2022, Figure 12.1)

This approach to circulation proved to be economically unsustainable as the output of scientific research expanded in the twentieth century, and as the post-war internationalisation of science increased the number of learned institutions needing access. A technological solution has been dreamed of since the 1950s, but it is only recently that electronic distribution might make a non-commercial, mission-driven approach to the circulation of knowledge affordable for some learned societies once more.

But money – whether as subsidy or income – is not the only thing that connects learned societies and journals. Both are associated with communities of scholars: the members of societies, and the authors, readers, reviewers of journals. The overlap between these communities explains why many societies run journals and why some journal communities ended up establishing societies to support them. Less commonly noted, however, is that the relationship between a journal community and a society community is not single or fixed.

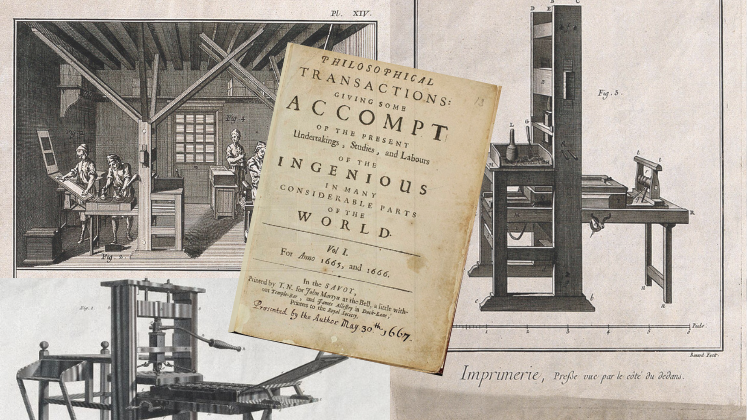

When the Philosophical Transactions was founded in 1665, the fellows of the Royal Society were not initially central to its authorship or its editorial/reviewing processes; but, at a time when the number of English-speaking scholars interested in the sciences was tiny, they were its core intended readership. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the journal became closely associated with the Royal Society, and the fellows of the society came to be the major source of content (either as authors themselves, or by communicating papers from their own networks). As editorial and reviewing processes became more complex, the fellows’ involvement in (and control of) these processes marked another way in which the Transactions had become a journal of, rather than for, the Royal Society. The intended audience of readers now stretched far beyond the fellowship of the Society.

Over the course of the twentieth century, the changing scale and nature of the scientific enterprise has shifted the relationship between the fellows of the Society and the communities associated with the journal. Fellows came to be just a tiny proportion of the authors and readers of the journals, and by the 1990s, they had ceased to be the sole source of editorial and reviewing expertise. In 1995, a publications review surveyed the fellows about the journals, and revealed little willingness to ‘publish their own (or their younger colleagues’) papers’ there; nor did the fellows admit to reading the journals more than ‘occasionally’. The fellows may still have expressed ‘goodwill’ towards the journals, but the mismatch between ‘the society community’ (small, British) and ‘the journal community’ (large, international) meant that the fellows lacked the sense of ‘ownership’ of the journals they had once had. For some of the fellowship and staff in the 1990s, the journals’ main function for the Society seemed to be to generate income.

There are undoubtedly still academic journals, likely in small specific fields, which remain tightly associated with a specific society, whose members comprise the majority of the authors, reviewers and readers of the journal. But, there are also many journals that fall somewhere in between that model, and the one exemplified by the big, modern scientific societies.

I begin to wonder whether our existing societies are in fact the best organisational structures to support scholarly communications in the future. Many of the functions of learned and professional societies (from research meetings, to policy and education work) seem to me to work best at national or regional level, and when there are substantial shared intellectual and social values among the members. But societies with a distinct local or national identity may not be the best structures for managing a future of scholarly communication that should be open, diverse and equitable, and operate on a global scale.

I still believe that (as the Royal Society argued in 1963) research journals need the support and oversight of communities of researchers, but reflecting on the changing relationship between the Transactions and the fellowship of the Royal Society leads me to suggest that we should pay closer attention to quite how the communities associated with journals and societies benefit from the relationship, and that we should ask that question in terms that are broader than finances.

Interested readers can read the recently A History of Scientific Journals: Publishing at the Royal Society 1665-2015, open access, via the link.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: In text images reproduced with permission of the author featured illustration LSE Impact Blog via Canva.

Fascinating observations Aileen, thank you, and it’s hard to disagree with your conclusions that societies and journals are no longer a natural fit in many cases. Society journals now account for a diminishing share of global scientific output, but while the fit is not perfect, it’s by no means clear that the increasingly dominant model of journals being owned by multinational corporations represents an improvement.

Thanks, Rob! As you imply, corporations have learned over the past 150 yrs how to scale up, from local to multinational. Learned/scholarly societies have, I think, been only partially successful in finding ways for local/national societies to collatorate and coordinate on a larger scale – and we see the consequences in academic publishing practices over the last 50 years.

In theory, I think the answer might lie in thinking about organisations that represent scholarly interests (rather than government, funder or shareholder interests) and that do function effectively at larger scale. I’m thinking of such organisations as the International Science Council (formerly ICSU and ICSS) that brings together many societies and scientific unions; or the International Academy Partnership that brings together many of the national academies of science/research; and there are also various university associations. In the 1940s/50s, equivalent (or predecessor) organisations took a serious interest in the effectiveness of what was then called the ‘scientific information system’. But maybe now, there seem too many vested interests?

Thank you Aileen for this insightful text, and congrats on your excellent book! You posed a very important question: “whether our existing societies are in fact the best organisational structures to support scholarly communications in the future”.

I agree that international journals may have become increasingly disassociated from their societies, especially when the societies are nationally based (though also many publishing societies are international). You mention small special fields as an exception but I think also the language of scholarly communication should be considered.

We need to look also beyond the English language journals targeted to international audiences, and we need a much more comprehensive understanding of the current global landscape of learned societies. In many non-English speaking countries around the world, for example in Finland, relatively small national societies are committed to publishing peer-reviewed journals in the local or national languages. For these societies, non-commercial, mission-driven approach to the circulation of knowledge remains often the only option.

You’re absolutely right: the use of a particular language may define (and limit) a community just as much as a subject specialism. When you say that ‘For these societies, non-commercial, mission-driven approach to the circulation of knowledge remains often the only option’, do you see this as a problem? Rather than an opportunity to be grateful that, in this context, the communities of the societies/academies and the journals continue to share interests and values? (I guess that ‘money’ may be part of your answer?)

Not really a problem, as these societies are really mission-driven. It is rather a challenge that they have very limited resources and rely much on voluntary work to sustain publishing activities.

Your analysis is from the point of view whether societies are best-suited to run publication programs. Although the criticisms may be on point (for effectiveness), the income to societies can be essential to running the societies programs (reducing dues, offering small grants, supporting conferences, giving awards, offering training, education, lobbying, and so on).

The thrust of the argument seems to sacrifice the science-building program of societies on the altar of “the best organisational structures to support scholarly communications in the future.” On balance, I cannot agree that “effectiveness” of dissemination is the only, or even the most important criterion here.

You’re right, of course, that I was primarily thinking of it from the point of view of the effectiveness of publishing, rather than the sustainability of learned societies.

I do know that some societies have come to rely heavily on income from their publications programme to fund the sorts of charitable/mission-driven activities you mention but, as I have shown elsewhere (Fyfe 2015, Fyfe 2022) this is (in historical terms) a relatively recent phenomenon, arising from political-economic conditions specific to third quarter of the 20th century. I think that those conditions no longer pertain, and society publishers will have to find some way to adjust. I do know that it can be difficult to imagine doing things any other way, if, as is often the case, the current trustees/council members have no memory of how the society worked before it had publishing income, but I’d like to put the history out there just to get people thinking about whether there could possibly be any other way of doing things. And the good news is that history does show that societies can and do adapt (though they may be very slow and bureaucratic about doing it)

Alas, conditions are changing. I was there before the publishing money, when our Society was months away from bankruptcy, and through the years of increased staff, award, cheap dues, professional support, travel support for early career professionals, significant investment in diversity initiatives, summer training courses, seminars in Op-Ed writing, outreach to government officials. I’ll admit, I am reluctant to see this second phase end. We are experiencing diminished circumstances, certainly, but it seems like some sacrifice on behalf of efficiency can be made in search of scientific excellence and inclusion. Not ready to convert to pessimism.

The real issue for me and my colleagues is to move to a model of article publishing that is open, driven by the scientific or other academic community, convivial, and well away from large international publishers with their high APCs and profit motivation. Publishing is a political act, subject to social justice criteria because of the need to challenge capitalist greed in the sector, and it is not just a thing you do at the end of a research project without considering who benefits from it. Societies can play some role, perhaps backstopping and mentoring individual journals, but they don’t necessarily need to run them, because that has forced them into revenue-raising in deals with Wiley, Routledge and their ilk over the last few decades, as you note.

In my discipline, the two big Anglophone societies, the RGS-IBG in UK wand AAG in the US, both use journal revenues to support their operations. Alongside $ from big annual conferences. I actually think they should move those journals away from commercial publishers, perhaps charge very small APCs direct to authors instead [compliant with Plan S mandates] , and employ some of the graduates of our degrees to assist in publishing geographical knowledge in-house, using APCs of under US$500. Print copies of journals are almost a think of the past, so cost savings there.

Our journal J of Political Ecology, has a nominal affiliation with a society, but that is all. The work is simply done by dedicated academic volunteers, and we have no income or expenditure other than our labour. Thsi model has worked since 1994, always online and free of charges.

We and others have set out ideas on the Commonplace at MIT – and in a previous article on this site.

Batterbury, S.P.J., Wielander, G., & Pia, A. E. 2022. After the Labour of Love: the incomplete revolution of open access and open science in in the humanities and creative social sciences. Commonplace. https://doi.org/10.21428/6ffd8432.5e24d46d

Pia, A.E., S.P.J. Batterbury, A. Joniak-Lüthi, M. LaFlamme, G. Wielander, F.M. Zerilli, M. Nolas, J. Schubert, N. Loubere, I. Franceschini, C. Walsh, A. Mora and C. Varvantakis. 2020. Labour of Love: an Open Access Manifesto for freedom, integrity, and creativity in the humanities and interpretive social sciences. The Commonplace https://doi.org/10.21428/6ffd8432.a7503356

Reprinted in ANUAC 9(1): 77-85. In Italian: ANUAC 9(2): 7-19. In Spanish: América Crítica 4(2): 157-162.

Batterbury SPJ. 2020. Open but unfair- the role of social justice in Open Access publishing. LSE Impact of the Social Sciences. http://shorturl.at/kvwxM

Batterbury SPJ. 2020. Spanish: SciELO en Perspectiva. https://blog.scielo.org/es/2020/10/29/abierto-pero-injusto Portuguese: OpNews. https://tinyurl.com/22dwpkds