Rosalind Edwards and Pamela Ugwudike discuss how the increased use of linked social data and predictive machine learning is changing the state’s relationship to families, from the here and now to an anticipated future and from one grounded in a sociological context to one of larger group pattern matching. Suggesting how this could facilitate a heightened regulatory and illiberal turn, they also point to movements claiming and working towards more just uses of social data.

States have long positioned families as a crucible of future citizens, and as both the source of and solution to a range of social harms. In our new book, Governing Families: Problematising Technologies in Social Welfare and Criminal Justice, we review different policy or intervention practices or technologies that, over time, governments have adopted in attempts to regulate or govern families. And we consider what contemporary neoliberal digital data-based family governance policies indicate for directions that these may take in the future.

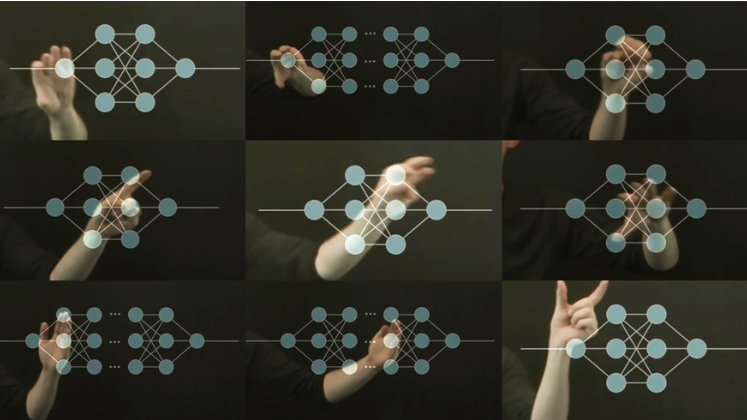

Contemporary family governance policies increasingly are operationalised through turning families into data and applying artificial intelligence that offers the promise of predicting dysfunctional social behaviour including crime, to inform interventions designed to prevent such problems. Social welfare and criminal justice systems become fused as administrative data sets are linked together in order to supply comprehensive information for the development and application of predictive algorithms to pinpoint families with data characteristics that deem them to require regulation.

Contemporary family governance policies increasingly are operationalised through turning families into data and applying artificial intelligence

Examples include family screening tools that purport to predict child neglect and abuse in social welfare and the forecasting risks of recidivism in justice systems across several Western and non-Western countries. Such algorithmic endeavours claim to be scientific and value-free, but their variables and categorisations perpetuate and reproduce gender, class and racial stereotypes and inequalities. For example, many of the characteristics identified and fed into algorithmic identification for child neglect and abuse models, or risk of recidivism models, are proxies for poverty. This means that higher income families, where children may be at risk, or where criminogenic risks may be present are hidden.

The application of predictive algorithmic analysis to data about families also signals a change in how families and family members are understood – a track from ‘what is’ to ‘what might be.’ The positioning of families in a predictive ‘what might be’ shifts focus away from social welfare and criminological concerns with identifying and intervening in specific families and family members’ lives, to spotlight mass units of data that are distanced from their lived social and cultural realities. There is a transmutation from the embodiments underpinning the databases into datafied entities in and of themselves, raising tensions and paradoxes.

While families remain a key site for state intervention, technologies for governing them are demonstrating departures from engagement with family members as individuals in the here and now towards control at this broader level. The focus becomes a need for comprehensive data about wider populations in order for AI to be applied and make predictive analyses. Populations need to be turned into a collection of quantified, machine-readable units of information in order to know about, model and predict – to construct the ‘pre-space’ of potential social transgressions.

This datafied mode of predictive governance ties the future of particular families and family members not to their own lived lives, but to the behaviours and data profiles of millions of other families. Families as a whole may be constructed as datafied objects in social welfare and criminal justice databases. But, they are not all subject to modes of governing intervention as solutions to continuing social and criminological representations of problems. Rather, it is poor working class and racialised families that are marked out for preventive intervention, algorithmically evaluated as culpable, dysfunctional, and a threat to economic and social order, obscuring the discriminations and structural inequalities that underpin family lives.

This datafied mode of predictive governance ties the future of particular families and family members not to their own lived lives, but to the behaviours and data profiles of millions of other families.

These sorts of paradoxes, encapsulated in tensions between the co-existence of here-and-now and predicted futures, between the disembodied datafication of populations and targeted intervention, may herald possible alternative directions for family governance. The development of digitised social care and criminal justice predication and decision-making may present a challenge for the civil liberties of families and their members.

All over the world, state governance of citizens has always involved restrictions on individual liberties, but datafication could herald a shift from neoliberalism to a form of neo-illiberalism. Families and communities increasingly may be coerced and compelled towards values and behaviours that governments deem to be desirable, underpinned and assisted by the roll-out of data-driven technologies of population surveillance. In the current era of datafication and dataveillance, ‘big data’ and administrative data feed governance technologies, this could involve more neoliberal surveillance, monitoring and punitive intervention to create and sustain technologies of familial self-monitoring, and hold families responsible for their own marginalization and disadvantage.

Datafication and algorithmic governance may enable illiberalism and authoritarianism, but there are indications of alternatives pulling in other directions. There are spaces to glimpse democratisation of governance and envisage the input of families themselves into technological modes. There are, for example, calls for data justice, proposals for obtaining public social licence for the uses to which data is put, and more participatory design practices that involve marginalised communities in building bottom-up data infrastructures.

The Indigenous data sovereignty movement for example points up the communal element in harms and in rights to control ownership and application of data in the face of a history of dispossession and exploitation that has led to marginalization and inequality, as against individual rights to ownership of personal information. In the context of algorithmic governance of families where datafication reaches beyond information about individual families to predict social dysfunctions including crime risks, the collective nature of big data means that families are affected by other families’ data more than they are by data about themselves. This is also the case where the consistent source and solution to these harms is constructed as poor working class and marginalised racialised groups, and disadvantaged mothers within these. Where the impacts are societal, not individual, civil liberty protections also need to extend from limited conceptions of individual harms and privacy rights towards notions of collective harms and communal approaches.

Collective ideas about social justice and equality raise fundamental questions about assumptions of ownership, representation, licensing and control of data and technologies for governing families. The collective ideas also offer alternative perspectives in which it is the algorithmic and other tools that are constructed as the object in need of governance and where material and social inequalities become represented as the social welfare and criminal justice problems.

This post draws on Rosalind Edwards and Pamela Ugwudike’s book, Governing Families Problematising Technologies in Social Welfare and Criminal Justice (Routledge, 2023).

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: LSE Impact Blog via Canva.

1 Comments