Analysing the recent government messaging on the value of university education, Zoe Hope Bulaitis, argues this rhetoric drastically simplifies how and where higher education adds value to society.

In a predictable manner, the calculation of the economic value of university courses continues to be the primary focus of the government’s interest in higher education in England. On 17th July 2023, Rishi Sunak and Gillian Keegan (the Secretary of State for Education) issued a joint press release titled “Crackdown on rip-off university degrees”. The statement is a political revival of the discourse on so-called “’low value degrees” building upon remarks previously made by Rishi Sunak during his bid for Tory leadership, and comments from former Secretary of State for Education Damian Hinds. However, beyond being good fuel for sensational headlines during the House of Commons recess, this statement is part of a longer narrative of setting minimum expectations for valuing higher education in England.

This statement represents the first public response to the Augar Review, or the “Review of Post-18 Education and Funding” (2019). The published report resulting from this review was over 200 pages long, exploring the topics of tuition fee prices, the provision of lifelong learning opportunities, access to maintenance loans, the employability of degree programs, and opportunities for widening access to higher education, as well as the relationship between universities and Further Education (FE) Colleges. Whether you like it or not, Augar undoubtably provided an expansive audit, so multi-layered that Nick Hillman (Director of HEPI) has described it as a “smörgåsbord not a prix fixe”. And so, after months of consultation, analysis, stakeholder engagements, and debate, we get the following response:

Crackdown on rip-off university degrees

This announcement sounds less prix fixe and more bargain basement to those awaiting more substantial or aspiring higher education policy. Identifying a minimum benchmark does not solve the challenges facing higher education in England. Whilst press campaigns about “rip off degrees” create divisiveness, there is an urgent policy need for nuance.

As others, such as Andy Westwood have argued, in terms of the effective development of “human capital”, higher education is only one part of a system, that requires investment rather than cuts. We need to better understand the extent to which higher education is connected to wider societal and regional challenges, such as employment skills-gaps, lagging investment in R&D, and the lowering of economic aspirations of young people.

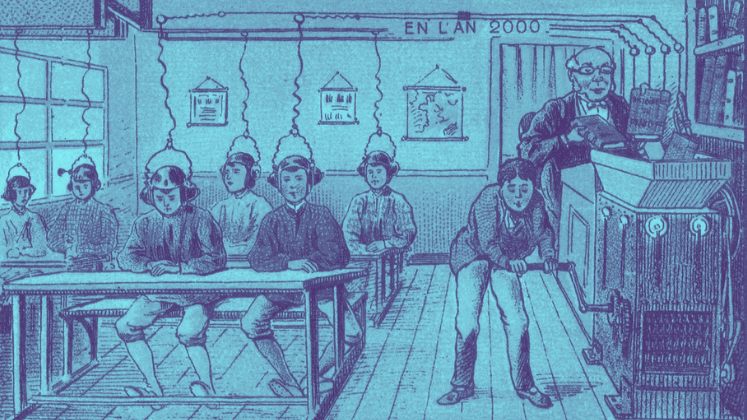

Fig.1: The Twitter account of the Prime Minister (@RishiSunak) promotes the publication of the “Crackdown on rip-off university degrees” press release.

But when looking at press communications from the Department for Education, we see a crude simplification of the issue of the value of and in higher education. Figure 1 sees the word “crackdown” seemingly misapplied from a law and order campaign. “Rip off” is equally heavy with liability; suggesting deception on the part of higher education providers. The sledgehammer pictured, presumably as a show of the brute strength in government action when taking down higher education criminals.

Rather than creating nuanced and interconnected systems for building people up, the closure of courses instead only knocks down pathways out of disadvantage

This language maps onto the funding of higher education in the last decade, with the student-as-consumer model adopted as a result of the Browne Report (2010) and recent Office for Students (OfS) policies shifting the costs of higher education to individual people. The rhetoric is not substantial enough to be a policy, but rather publicity for an ongoing system of valuation. It belongs to the twenty year old discourse of demonising ‘Mickey Mouse’ degrees (even if such courses remain hard to pin down), the prioritisation of Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) subjects over Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH), and a general disregard of the wider access to education that post-1992 and FE Colleges provide.

Rather than creating nuanced and interconnected systems for building people up, the closure of courses instead only knocks down pathways out of disadvantage. In real terms, it means that student numbers will be capped and individual university courses scrutinised against conditions of employment post-graduation (see wider discussion here and here). Under the new rules the OfS penalties may be imposed on courses where student fewer than 60% find a place in further education, professional employment within a 15-month period after graduation. Furthermore, the B3 conditions stipulate the necessity for at least 80% of full-time students to continue their academic pursuits, and a minimum of 75% of full-time students to successfully complete their chosen courses. In effect, this places pressure on universities to avoid risks in course design and student cohort. In a parallel development, foundation year courses provided by universities, specifically designed for students lacking prior academic qualifications, with a particular emphasis on disadvantaged or mature students, will be subject to newly imposed constraints.

What is unsaid in the crackdown on “low value courses” is the sense the students taking these courses are not seen to be successful contributors to economic growth. I would encourage those interested to read Antony C. Moss on the disconnect between quality and inequality in terms of educational experiences in the UK. If the government is truly committed to levelling up, it might need to start thinking about the benefit of having more mortar (boards) and less sledgehammers.

Readers can also listen to Zoe, discussing this issue on The Bunker podcast, First degree burns: Why Sunak’s wrong on universities.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Adapted from OpenClipart-Vectors via Pixabay.