Drawing on a decade of data on academic publications, Dan Brockington, Paolo Crosetto, Pablo Gómez Barreiro and Mark Hanson argue that an academic publishing industry based on volume poses serious hazards to the assessment and usefulness of research publications.

Would so many academic articles be published if publishers’ profits were lower?

We all know about the pressures to publish. The incentives to generate more and more material, to ‘overwhelm’ with a long CV are powerful. Upon retirement, scientists like to be celebrated for the hundreds of articles that they have written. Historians will count their books. And if you are just starting out, and haven’t published? Well you know how the phrase goes: publish or …

Decades of this behaviour has put academia in serious trouble. There are now so many papers being prepared that it is hard to find the reviewers for them. And as for reading them – well ‘peak fact’ was probably reached years ago. If we compare just the indexed articles with the growth in PhDs then it is plain that there is a strain in scientific publishing (Fig.1).

Fig.1: Growth in indexed articles (solid line) and new PhDs (dotted)

But in looking at ourselves, at researchers, for the cause of this problem, are we looking in the right place? What if we turned the spotlight on the publishers? To what extent is their behaviour, or more accurately business models, driving the growth in papers?

In a new pre-print examining the strain we have argued that we need much more careful scrutiny, and better governance, of publishers’ behaviour. Based on an analysis of millions papers in the Scimago archive, and our own web-scraping, we highlight five trends:

- Article growth comes from numerous publishers, both those who sell journals via subscription and by those who levy article processing charges on gold open access papers (Fig.2A).

- Some publishers’ turnaround times (from paper submission to article publication) have become short and homogenous. We would expect them to be diverse because papers’ needs are different.

- More articles can also be created by lowering rejection rates. But there are no clear trends in rejection rates across the sector. Our modelling showed that the best predictor of patterns in rejection rates was the publisher.

- Special Issues are a major driver of growth among some (but not all) gold open access publishers. We found that Special Issues are also associated with lower rejection rates and more homogenous turnaround times.

- By comparing different measures of impact factor we could show that there has been impact inflation across the sector by all publishers (Fig.2B). This is a classic case of Goodhart´s law in operation.

What do we learn from all of this? First, it suggests some hard questioning of publishers. How is editorial independence maintained in current publishing environments? We must ask this given that some of the metrics are tending to change in all the same directions within specific publishers.

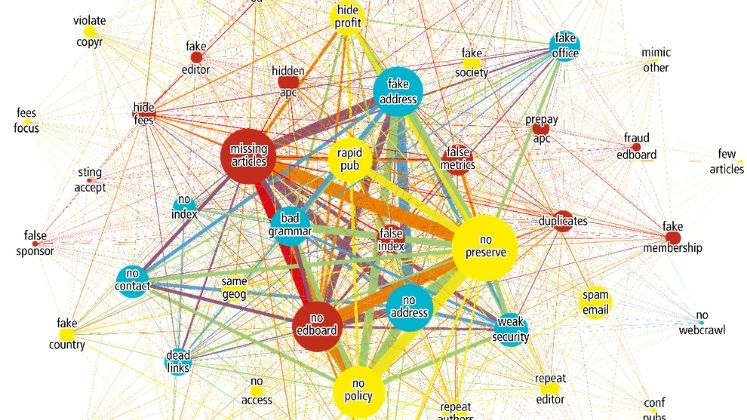

Second, we need a new language to talk about publishers behaviour. Currently we seem stuck with the categories of ‘predatory’ and ‘legitimate’. But maybe we need more nuanced analyses. It is notable, for example, how much of the twitter attention of our article labelled MDPI as ‘predatory’. MDPI does stand out in our analysis. It stands out with bells on. It has the most growth of papers, most special issues, shortest turnaround times, decreasing rejection rates, highest impact inflation, and the highest within-journal mean self-citation (Fig 3). But at the same time, it is a member of the Committee of Publication Ethics that promotes ‘integrity in research and its publication’. Other publishers, also COPE members, are doing what MDPI does, just less copiously. Publishers that are thought to be ‘legitimate’ by the publishing community are doing things we have not known before in academic publishing. Categories like ‘legitimate’ or ‘predatory’ do not suffice to capture the phenomenon we observe.

Fig.3: Trends across all publishers

The other problem with terms like ‘predatory’ and ‘legitimate’ is that this dichotomy labels behaviour which makes handsome profits off free academic labour as ‘legitimate’. Elsevier’s profit margins have long raised eyebrows, and at one point led to a stand-off with the University of California. Look again at Fig 2A to see which company is churning out by far the most indexed publications. Similarly, Nature’s leverage of its brand as part of an APC based publishing model has provoked popular derision. Should these business models be called ‘legitimate’? Plan S goes some way towards demanding transparency on what services publishers offer. But it stops short of asking how profitable those services are.

If we are to understand the changing world of academic publishing then we need the data we have unearthed to be more easily available. Academic publishing is simply not transparent enough.

Greater transparency would make it easier to bring in the better policing and governance academic publishing needs. Publishers need to police themselves more effectively. They could be made to do so by major research funders. One obvious step is to discourage so many Special Issues which are driving much of the recent increase in papers. Funders and employers need to discourage researchers from taking part in the publish or perish culture.

Some of the increase we have observed is welcome. It has to be. It reflects a more inclusive research world where productive researchers are not confined to the Global North. However, we need to find a way of making research more open, without opening the floodgates to poor science. Ultimately ‘science’ deserves that name in part because of the careful scrutiny scientists demand of their work. Too much indexed output receives too little scrutiny, especially if reviews are churned out ever faster while rejection rates decline.

The dysfunction, and obvious beneficiaries, of scientific publishing today poses a profound challenge: Can we reimagine scientific publishing so that it is unaffected by profit motives? This would be most easily done if the organization, and funding, of academic publishing created little profit. That is a prospect that could indeed transform academia.

This post draws on the authors’ preprint, The strain on scientific publishing, published on arXiv.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: James Allen via Unsplash.

> Can we reimagine scientific publishing so that it is unaffected by profit motives? This would be most easily done if the organization, and funding, of academic publishing created little profit.

Yes, easily. “Publishing” per se is obsolete; working papers and other formats are fine. We need to commission credible, public _expert evaluation and rating_ of research, and the *rating* and use of a body of research should be what makes a researcher’s career, not a list of publications in bound volumes.

Also research should often be long-term _projects_, continually improved in response to feedback, new data, and new techniques, rather than a scattering of overlapping pdfs that ‘land’ in various journals.

Hiring experts to do this evaluation, independent from journals, will cost some time and money, but I think it will cost far less, and provide far more (for researchers, research users, and funders, than our current bureaucratic, opaque and convoluted system of (often for-profit) journals.

The Unjournal (unjournal.org) is doing this. We’re focusing on work with a global impact/relevant to global priorities, thanks to grants from the Long Term Future Fund, and the Survival and Flourishing Fund. You can learn about our approach (feedback welcome) and engage with us (see unjournal.org).