Drawing on findings from the SHAPE in Schools project, Tallulah Holley argues that the prioritisation of STEM subjects in schools risks the creation of a pipeline of students unable to draw on the full range of approaches necessary to address today’s global challenges and suggests we need more polymaths and less specialists to address impending polycrises.

Today’s most pressing challenges range from the economic to the environmental, the geopolitical to the technological. From their complexity emerges interrelated issues that require multifaceted and creative solutions. Despite this, much of the discussion around addressing global challenges centres solely on scientific and technological approaches to safeguard our future.

This narrative translates into education policy and increased funding for STEM subjects. Rightly so; we need strong STEM skills and equal access to STEM education in order to tackle such challenges. However, such a focus has in turn led to a more unbalanced school curriculum and a privileging of certain subjects to the detriment of others. In short, SHAPE subjects (social sciences, humanities and the arts) are being overshadowed due to a singular drive to support STEM alone.

A mixed outlook from SHAPE in schools

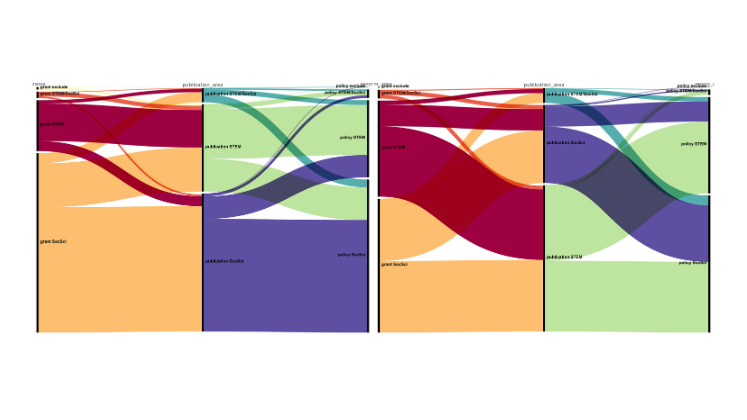

The picture for social sciences, humanities and the arts is not homogenous. At A-level, humanities have seen a 10% decline in entries across England, Northern Ireland and Wales from 2018 to 2023. Arts have seen a 6% decline over the same period, though from a far lower starting point. By contrast, social sciences have increased by 33% and STEM by 8% since 2018.

The number of learners trained in scientific methods of investigation has therefore increased markedly in only five years. Relatedly, the combination of subjects taken by each learner is also becoming increasingly narrowed into one disciplinary area. As a result students are losing the ability to move between subject disciplines. This in turn could lead to a false assumption that students are either STEM or SHAPE, scientific or artistic, logical or emotional. Dichotomies that are distorted and troubling.

the combination of subjects taken by each learner is also becoming increasingly narrowed into one disciplinary area.

Shifts at GCSE and A-level are playing out across the student pipeline, creating such small cohorts of students in some disciplines that university departments are threatened with closure. Concern over modern languages at Aberdeen University is only the most recent example and it will not be the last.

Whilst uptake data and enrolment onto degree programmes are easily measurable, they only form part of the puzzle. Perceptions of disciplines and their methods of investigation are shaped by narratives in the media and from policymakers that are then repeated in schools, at home and by local communities.

In 2020 SHAPE in Schools was funded by LSE to promote SHAPE within primary and secondary education. Over two years, we launched a series of learner workshops with 11 pilot schools across the UK, the aim of which was to demonstrate the relevance of SHAPE subjects and increase their visibility within schools. As part of our research, we surveyed 626 learners aged 12-14 to understand their views on the importance of SHAPE and the interconnections between subjects. We asked learners to rank 12 subjects based on preference and then importance for future careers.

Learners were also more likely to consider STEM subjects as important for their future career and to believe they would go into a career in STEM.

The findings showed that preference for SHAPE subjects was far more polarised than for STEM. While many learners ranked art and English highest, modern languages and religious studies most often ranked lowest. By contrast, STEM subjects sat more consistently across the rankings with fewer extremes of opinion. Learners were also more likely to consider STEM subjects as important for their future career and to believe they would go into a career in STEM. The difference between the mean placement of SHAPE and STEM subjects based on enjoyment was 0.54 in favour of STEM. This difference rose to 1.44 for importance for careers.

The implicit and explicit perceptions communicated to learners shape their opinions of the subjects they learn. When the contributions of some subjects are valued less than others, the contributions of those who wish to study those subjects are also called into question. The issue is also gendered. Since female learners are more likely to favour SHAPE subjects, what are we saying about female contributions if SHAPE subjects are seen as secondary to STEM?

There is a need therefore to celebrate every subject and appreciate its place within the wider education landscape. In doing so, we would convey to learners their worth and the role they can play in tackling today’s global challenges.

Equipping polymaths

The British Academy’s Right Skills report categorises core SHAPE skills and behaviours as follows: communication and collaboration; research and analysis; problem-solving and decision-making; and adaptability and creativity. These skills prepare SHAPE students to be more flexible and resilient, but they are also foundational to all roles in the workforce. Such skills highlight the need for learners who wish to go into STEM careers to be knowledgeable in the social sciences, humanities and the arts as well.

Indeed, there are an increasing number of interdisciplinary courses in Higher Education which teach arts and humanities alongside the sciences, emphasising the value of both. These programmes are often problem-led “to prepare for an increasingly complex and uncertain world”.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2023 identifies the key risks facing the world over the next decade. Crucially, it highlights that individual crises are not disconnected from each other but instead interact “to form a “polycrisis” – a cluster of related global risks with compounding effects, such that the overall impact exceeds the sum of each part.” Consider, for example, the impact of climate change on migration, access to clean water and even the preservation of endangered languages.

Our world is connected, our education should be too. Complex global risks call for creative, multidisciplinary responses.

A mono-mindset focused on problem-solving through STEM alone fails to capitalise on the plethora of tools available to us and impoverishes every discipline in the process. If collaboration is a core SHAPE skill, we need to work together, bringing to the table people from a wide range of backgrounds, experience and expertise. Such approaches cannot be the reserve of researchers and Higher Education institutions. We need a clearer articulation of the value of SHAPE and STEM among learners of all ages.

Our world is connected, our education should be too. Complex global risks call for creative, multidisciplinary responses. We need polymaths to respond to polycrises.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Adapted from Sam Balye via Unsplash.

Thank you for sharing your findings. I always say that we need a SHAPE curriculum alongside STEM. Otherwise, students would not be able to cope with today’s polymath nature of society.

You’re absolutely right! A balanced curriculum that includes both SHAPE and STEM is essential for developing well-rounded individuals. By integrating these disciplines, we equip students with diverse skills and perspectives, enabling them to thrive in a multifaceted world and adapt to the ever-evolving demands of society.

Yes! I now make it a point in all my talks to argue against STEM. I point out that I, myself, am highly trained in STEM (*I’m even a member of the U.S. National Academy of Engineering), but the point of these fields, especially Engineering and Technology, is to lead to a better life for people, so shouldn’t they (we) also understand people? The fields of STEM are all important, but insufficient. And SHAPE isn’t enough. People need to understand economics, business, and politics, because these factors play major roles in our civilization. We need more generalists, more people widely educated, whether self-educated or formally trained does not matter, but those with a wide understanding of all life, of the environment, and of the political structure and history of our civilizations.

Simply adding new topics is the wrong solution. STEM and SHAPE are still taught subject by subject — in siloes–each in isolation, and each divided into specialties — sub siloes. We need more courses that are integrated across disciplines, project-based courses, where the combination of different forms of knowledge can be recognized as essential. This makes the courses more interesting and also does a better job of illustrating the importance of a broad base of experience and knowledge.

Thank you for writing this article.