Our new open-access website contains detailed results of all Mozambique elections since 1999 – right down to local level in most cases. This promises to be a valuable resource for anyone interested in issues of fraud and democracy, explains visiting Senior Fellow, Joseph Hanlon.

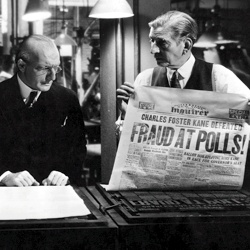

In the 1941 film Citizen Kane, newspaper owner Charles Foster Kane is standing for governor. Between the closure of the polls and the announcement of the results, the newspaper awaits with two possible front pages. One is headlined “KANE ELECTED”; the other says “KANE DEFEATED, FRAUD AT POLLS!”

In the 1941 film Citizen Kane, newspaper owner Charles Foster Kane is standing for governor. Between the closure of the polls and the announcement of the results, the newspaper awaits with two possible front pages. One is headlined “KANE ELECTED”; the other says “KANE DEFEATED, FRAUD AT POLLS!”

Some things never change. There have been five multiparty elections in Mozambique since the end of its civil war in 1992. Frelimo won them all, but Afonso Dhlakama, head of the opposition Renamo and its presidential candidate in all five, claims he won them all, and was deprived of victory by fraud.

There is fraud in Mozambique elections, including ballot box stuffing and invalidating opposition ballot papers. In 2013, local elections, district and provincial election official changed the results in the town of Gurué to give the victory to Frelimo. The Constitutional Council overturned the result and forced a rerun of the election, which the opposition Mozambique Democratic Movement won. Key to this was a parallel count run by local civil society showing that MDM won, extensive media coverage, and judges willing to investigate.

But how serious is the fraud?

We have now compiled a data set with detailed results from Mozambique elections since 1999, in most cases with results from individual polling stations, and are now launching a Mozambique Elections website to allow researchers to study the results.

The website is unusual because it allows comparison of individual polling stations in ways that are particularly amenable to statistical analysis. For example, preliminary statistical tests of the 15 October 2014 national election suggested 6% of polling stations showed signs of ballot box stuffing, while 4% showed indications that polling station staff had improperly invalidated ballot papers for the opposition.

Much more detailed statistical tests are possible. This is part of an international research collaboration, and we invite students and other researchers to use the data and to share their findings via our website.

Fraud at Polls

“Fraud at polls” – yes. But was there enough to make a difference?

The data set is unusual because the structure of Mozambique elections provides very local data. Mozambicans must register every five years, and most register and vote at their local school. When a book of 800 voters is filled, this is assigned to a polling station in one of the classrooms. The count is done in each polling station and the result posted there, which also allows parallel counts.

Because the people who register are all from the same neighbourhood, one might assume the votes in all classrooms would be similar, and this can be tested. One classroom with a 90% turnout when the rest had 40% would be very suspicious; similarly one classroom with many more spoiled ballot papers and many fewer votes for the opposition could indicate that the ballot papers had been intentionally spoiled.

Many other checks are possible. For example, voter turnout was 49%, and, as expected, turnout in individual polling stations followed a normal distribution around that median value. But there was also an unusual group of polling stations with turnout over 90%, which suggests ballot box stuffing.

Mozambique is also unusual because the ruling party, Frelimo, despite being willing to cheat in order to remain the predominant party, also accepts a free press and relative electoral transparency. Press freedom in Mozambique has allowed me to edit the Mozambique Political Process Bulletin since 1992, with increasingly detailed election coverage. For the 15 October 2014 national elections, we published a daily newsletter based on reports from 150 correspondents, one in each district. Most were from community radio or local newsletters, and they reported on the campaign, voting and counting. Their rapid reports ranged from registration computers that did not work to arrests of opposition campaigners, and meant election officials knew they were being watched. This played a key role in what proved to be an orderly campaign and relatively well run election.

The election law bans the use of state cars in the campaign, but ruling party Frelimo often ignores that. So we began publishing registration numbers of state cars in the campaign – sent in by our correspondents. The system only works because Frelimo, despite being willing to cheat in order to remain the predominant party, also accepts the free press. In Mozambican market towns, everyone knows everyone else so we could not keep the identities of our correspondents secret. One correspondent told us that his friend, a Frelimo official, joked with him: “you are making it hard for us – we had an instruction from national level to stop using ministry cars.”

They cheated even though they knew we were watching. But only a much more serious analysis of our new data set will tell us if media and civil society vigilance kept the fraud at a low level.

Joseph Hanlon is a Visiting Senior Fellow in International Development