Yana van der Meulen Rodgers, Ernestina Coast and Nicky Armstrong argue that Trump’s global gag rule will not only be ineffective in reducing the number of abortions, but will also harm women’s’ reproductive health as well as making other crucial health services less available to women, men, and children around the world.

Who influences whether women in poorer countries can access abortions and other sexual health services? It may surprise you, but the US president has an important part to play. This is because of the so called “global gag rule”(GGR), a US foreign policy that cuts family planning and reproductive health assistance to any healthcare provider overseas which offers and provides abortions.

Having previously been rescinded by President Obama in 2009, this policy was reinstated by Donald Trump in 2017 just three days after he entered office. Under Trump, any non-governmental organisation abroad can only receive US assistance if it does not use funding from any source to provide services that relate to abortion, even counselling. The extension of the policy to cover all global health funding – including funding to organisations that treat HIV/AIDS, fight malaria, and work in maternal and child health – has created a funding shortfall of approximately $8.8 billion.

The GGR has been applied in some form by every Republican president since Ronald Reagan in 1984. Since then, the policy has remained a hallmark of Republican administrations, with Democratic presidents scrapping it and Republican presidents reinstating it. The name ‘global gag rule’ comes from its prohibition of even counselling women on abortion or advocating for its legalisation, effectively placing a gag on what healthcare providers can say. Additionally, under the GGR, foreign NGOs cannot even use their own funding for abortion-related activities.

In its official directive, the Trump administration referred to George W. Bush’s Presidential Memorandum, which stated “It is my conviction that taxpayer funds should not be used to pay for abortions or advocate or actively promote abortion, either here or abroad.” The Trump administration ordered the Secretary of State to extend this Memorandum to “global health assistance furnished by all departments or agencies.” The reinstatement of this policy by Trump was widely expected, but his expansion to cover all forms of global health funding generally took health care providers by surprise. While the GGR is intended to reduce abortion rates, when it was last invoked in 2001 by Republican President George W. Bush, it prompted an increase in the number of abortions in countries affected most by the withdrawal of healthcare funding and where abortion laws are strictest. These countries include Guinea, Mozambique, Zambia, and Senegal in Sub-Saharan Africa, and Bolivia and Nicaragua in Latin America.

Why do abortions go up when there is less healthcare funding available?

We looked at Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 51 developing countries, covering about 6.3 million women per year. When the GGR was in place in 2001, women in highly exposed countries were more likely to have an abortion compared to women in less exposed countries, and before the policy was re-imposed. Women in Latin America became three times more likely to get an abortion and twice as likely in Sub-Saharan Africa. Abortion rates rose in both these regions despite their very restrictive legal regimes around abortion. Latin America has some of the most restrictive abortion laws in the world (in fact, four countries in that region – Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Dominican Republic – still have complete abortion bans in all circumstances, even in cases when the woman’s life is in danger). The implication of this research is that in these regions with restrictive national abortion laws, more abortions were performed under unsafe conditions that heightened women’s risks of complications. Women will find a way to have an abortion if they need to, even if it is difficult, dangerous or expensive.

The main reason that the GGR led to an increase in the likelihood of abortion in these regions was the major disruptions to family planning services brought on by the withdrawal of healthcare funding. A series of site visits and interviews led by Population Action International in a number of developing countries indicate that the funding cuts beginning in 2001 resulted in clinic closures, health personnel layoffs, fewer services, and reduced contraceptive supplies. This reduced access to contraception led to more unintended pregnancies and thus higher abortion rates. Although there is no data yet on whether abortions have risen under Trump’s expansion of the GGR, new qualitative research conducted in Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa points to reductions in service delivery as well as new fees for contraceptives that used to be free.

Of the countries exposed to the global gag rule (GGR), abortion rates only fell in South and Southeast Asia. It is not clear why Asia stands out in this way, but a simple model suggests that the relatively high overall cost of abortion (including non-pecuniary costs) compared to giving birth in those countries is one of the reasons. This isn’t to say that Asian countries were unaffected by the policy.

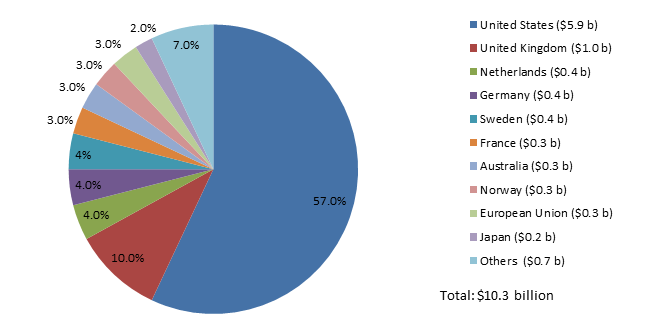

With its pockets of overcrowding, gender inequality, and growing rates of HIV infection (in 2017, countries in the Asia-Pacific reported 280,000 new HIV infections), this region cannot afford to see disruptions to its health services caused by US restrictions on global health funding. Bilateral aid from developed countries is the dominant source of population assistance, and the US is by far the single largest donor country, so any restrictions in US funding will have a large effect (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Population Assistance by Source Country, 2012

Unsafe abortions

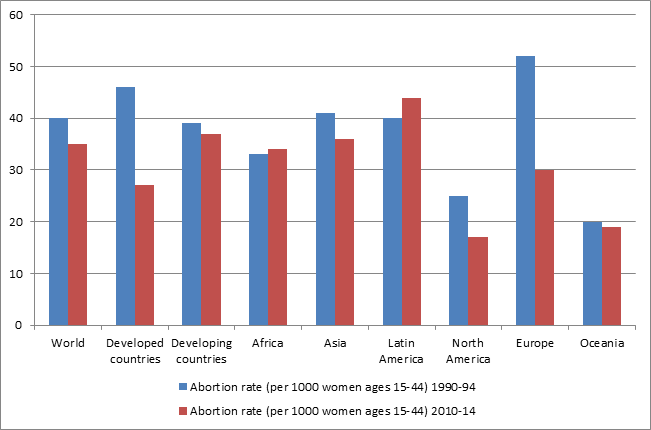

Globally, abortion rates have fallen over time, as Figure 2 illustrates. Most of this decline has occurred in developed countries, while the estimated decline in developing countries is much smaller. Despite intense lobbying efforts by anti-abortion groups, strong stigmas against abortion, and highly restrictive abortion laws in many countries, abortion remains a common gynaecological procedure across the globe. One quarter of all pregnancies end in abortion, up from 23 percent in the early 1990s.

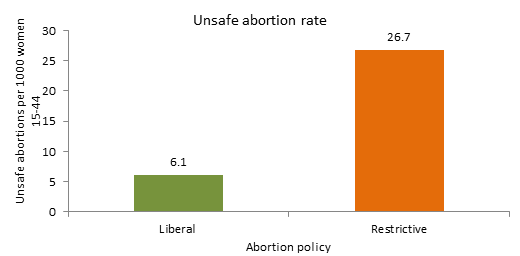

In the face of the overall decline in abortion rates, the absolute number of abortions considered unsafe according to standards set by the World Health Organization has remained high. Between 2010 and 2014, about 25 million unsafe abortions took place globally each year. This figure appears to be on the rise since 2008, when approximately 21.6 million unsafe abortions took place globally. Moreover, data from the United Nations indicate that countries with highly restrictive abortion laws have substantially higher unsafe abortion rates (Figure 3).

Abortion accounts for up to 31,000 deaths each year, representing about 10 percent of maternal fatalities around the world. Although this number of abortion-related deaths is high, it has declined considerably since 1990 when a staggering 546,000 maternal deaths were attributed to unsafe abortions. These deaths and complications are entirely preventable. Investing in sexual and reproductive healthcare services, providing effective contraception, and improving women’s access to safe abortion are the key.

Funding gap

It is still too early to tell exactly how much funding has been cut already under Trump, but projectionsindicate that at least 1,275 foreign NGOs and close to $2.2 billion in funding allocated to them could be subject to the terms of the 2017 expanded global gag rule. This is a substantial sum of money that is difficult for other donor countries to match, although there are efforts to do so. The effects are projected to be most severe in Sub-Saharan Africa, the region that is still most exposed to the wider effect of the GGR.

Case study evidence from Mozambique in a new report by the Center for Health and Gender Equity has documented some of these effects. The Mozambican Association for Family Development (AMODEFA), a leading provider of sexual and reproductive health services in Mozambique that includes HIV prevention and treatment, decided to not comply with the terms of the GGR. It expects to lose two-thirds of its total budget and has already been forced to close clinics across the country and lay off 30 percent of its staff, resulting in a drastic reduction in services provided by clinics that did stay open. For example, an AMODEFA clinic in the southern city of Xai Xai reported that the number of HIV consultations it provided dropped from 6,799 to 833 by the end of 2017.

This finding is not unique to Mozambique. New research by a team from amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research and Johns Hopkins University covering 45 countries shows that one third of all implementing partners in the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (Pepfar) programme have already reduced or stopped their services or anticipate doing so as a result of the expanded GGR. These services include the provision of contraception, cervical cancer screenings, and adolescent health guidance.

The policy could also have indirect “trickle” effects such as less investment in girls’ schooling if parents believe their daughters will have reduced access to contraception later in life and won’t be able to delay having children.

Unintended consequences

Evidence suggests that the GGR – renamed by the Trump administration as “Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance” – does not achieve its objectives in most countries that receive US foreign aid. Instead, it appears that the policy is counterproductive, places lives at risk, and has unintended effects.

Critics of the GGR argue that a constructive and cost-effective approach for US financial assistance is to support the integration of family planning and safe abortion into a full range of reproductive health services. For example, Barbara Crane, a former official with the reproductive health organisation Ipas, made a strong case for integrated health services as the key for reducing unsafe abortions:

“We need stronger health systems and we need integrated service delivery. One of the problems is that family planning has often been kept separate from other health service delivery and verticalized, and abortion even more so. How do you break the cycle of unwanted pregnancy and unsafe abortion? You need to help women have access to services.”

The cost of providing this for women in a developing country runs to just $8.56 per person a year. It is imperative for US foreign aid policy to support this agenda rather than marginalise women and their reproductive health with ideologically-based funding restrictions.

Professor Yana van der Meulen Rodgers (@YanaRodgers) is a Professor at Rutgers University and Faculty Director of the Center for Women and Work. Yana is the author of the new book The Global Gag Rule and Women’s Reproductive Health: Rhetoric versus Reality. Yana served as President of the International Association for Feminist Economics in 2013-14, and she has served as an associate editor for Feminist Economics since 2005.

Professor Ernestina Coast (@LSE_ID) is Professor of Health and International Development in the Department of International Development at LSE. She is the Principal Investigator of “Improving adolescent access to contraception and safe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa” and is the thematic lead for sexual and reproductive health on “Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence”.

Nicky Armstrong (@NickyArmstrong0) works in communications for both the Global Health Initiative and the Latin America and Caribbean Centre at the LSE. Nicky also works with PEN focusing on the freedom of speech and has a background in International Relations with a focus on US foreign policy and American exceptionalism.

This article was first published on the LSE USAPP Blog.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.