Geoff Goodwin tells us about his findings from a research project he conducted on International Development students about how they perceive and navigate multi and interdisciplinarity.

As a field of study, international development combines multiple disciplines, including economics, politics, sociology, anthropology and geography, and various methodologies, including qualitative, quantitative and mixed approaches.

Within this contested space, there is considerable disagreement about how disciplines should be used to explore and interrogate international development. Put crudely, some academics favour multidisciplinarity while others advocate interdisciplinarity. The former brings together different disciplines while respecting disciplinary boundaries and identities. The latter transgresses boundaries and actively seeks to integrate and synthesise insights from different academic disciplines.

While the difference between the two approaches appears small, it has big implications for teaching and learning. I became aware of this at LSE while teaching in the Department of International Development and studying for the Postgraduate Certificate in Higher Education.

I decided to investigate it empirically by conducting a small research project within the department. I was particularly interested in understanding how students perceive and navigate multi and interdisciplinarity and how they learn concepts and theories within these settings.

To get a sense of this, I conducted a survey, focus group, and small number of interviews with students enrolled on international development programmes in 2017-18, including degrees run with other departments.

The findings, while in no way representative of the entire cohort, offer insights into teaching and learning international development, and into student experiences of studying in the department and university. Here, I will highlight a couple of points, focusing on multi and interdisciplinarity.

Firstly, students saw a high degree of disciplinary diversity in their programmes, albeit with a concentration in economics and politics. When asked in the survey which disciplines are represented on their programmes, students selected the following from a set list: economics (84%), politics (84%), sociology (66%), history (61%), anthropology (58%), geography (29%), law (18%), philosophy (18%) and finance (10%).

This reflects the range of disciplines incorporated into the programmes offered in the Department of International Development as well as the choice of optional courses available to students outside the department.

The survey data give some indication of this. The most commonly listed options were international development modules (top three: DV407 Poverty, DV490 Economic Policy Analysis and DV420 Complex Emergencies). However, numerous options were also listed from other departments, including management, methodology, anthropology, and gender. Hence, student perceptions of disciplinary diversity were not solely shaped by their experiences of studying in the Department of International Development.

With this in mind, 70% of respondents to the survey viewed their degree programmes as interdisciplinary, while 30% considered them multidisciplinary. The balance shifted when asked about their modules, with 63% selecting interdisciplinary and 37% choosing multidisciplinary.

The difference, while small, gives some indication of how disciplines are combined at the programme and module level, with students seeing or creating greater integration and synthesis at the higher level.

The focus group provided greater insight, with the participants noting the degree of multi and interdisciplinarity varies considerably across modules. While some academics integrate multiple disciplines into their courses and lectures, others appear to teach from a single disciplinary perspective.

One student took particular exception to this, believing that the teachers on the modules she studied ‘have very little regard for other disciplines and look at issues their specific way’. She went on to say that ‘I really did not like that at all; it really bothered me’.

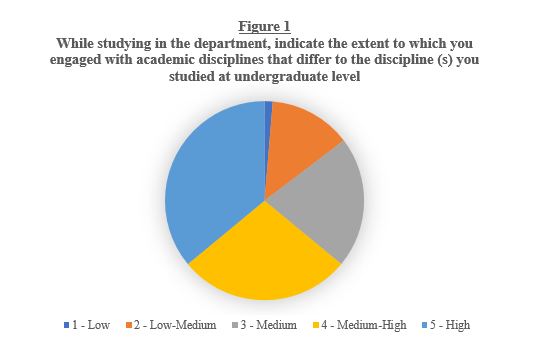

Yet, there was broad agreement among students over the extent to which they crossed disciplinary boundaries while studying international development programmes. When asked in the survey, most students responded that they actively engaged with different disciplines (see Figure 1). Only 15% reported a relatively low level of engagement.

The focus group and interviews suggest that this was often a deliberate learning strategy. For example, one participant in the focus group said ‘I really tried to reach as far as I could’, explaining how they selected modules on health, poverty and feminist economics to branch out from their orthodox economics background.

However, one participant in the survey suggested a more passive approach, noting that ‘you have to follow the material, and it often takes you into other disciplines.’ This indicates the way the curriculum can be designed to encourage students to step out of their comfort zones and engage with different disciplines.

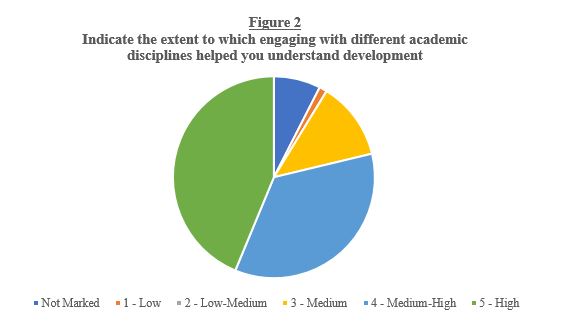

Revealingly, students were unequivocal in their belief that studying multiple disciplines enhanced their learning. The vast majority of respondents to the survey believed that it enabled them to develop a more sophisticated understanding of international development (see Figure 2).

Interestingly, the bulk of students who participated in the survey believed that working with different academic disciplines strengthened their understanding of the discipline (s) they studied at undergraduate level.

For example, one student explained in the survey how studying development and anthropology helped them arrive at a richer understanding of the role electrification plays in the process of development, having previously studied electrical engineering.

To sum up, the initial findings of this research suggest international development students have a thirst for branching out into different academic disciplines and see the intellectual and practical value of not remaining within the confines of a single discipline.

This indicates the need to take the issue of multi and interdisciplinarity seriously and ensure student ideas and perspectives are fully integrated into debates about how to approach it at LSE and elsewhere.

___________________________________

I am extremely grateful to the students who participated in this project and to Maria Camila de la Hoz Moncaleano for superb research assistance. Thanks also to Claire Gordon, Colleen Mckenna and Erik Blair for their encouragement and guidance. The Teaching and Learning Centre kindly supported this research through a Swift grant.

I would be delighted to hear from current or former international development students who would like to participate in the next phase of this research. Please contact me at geoff.goodwin@qeh.ox.ac.uk.

Geoff Goodwin (@GBGoodwin ) is Departmental Lecturer in Development Studies at the University of Oxford and Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. He researches and teaches within an interdisciplinary framework, drawing principally on economics, sociology, anthropology and history. His current research focuses on community water management in Ecuador and Colombia.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

nice article