MSc African Development candidate, Johanna Horz dissects the link between Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and politics in Sierra Leone, and questions whether the recent nationwide ban on initiation ceremonies can be seen as a milestone for women’s protection?

Becoming a woman in Sierra Leone is near-synonymous to being initiated into the Secret Bondo Society, which 90% of women belong to. This Society provides women with agency and social protection – but initiation into the Society also mandates undergoing Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). FGM has severe consequences ranging from life-long physical and psychological trauma to death, leading to the proliferation of campaigns against FGM worldwide. With the fourth highest FGM prevalence in the world, Sierra Leone has been termed “ground zero” for eliminating FGM due to its complex embedment into society through Bondo Society. 2019 has been publicized as a major stepping stone for women’s rights in Sierra Leone. In January 2019 the Sierra Leonean government “with immediate effect banned initiations country wide” and in February rape was declared a “national emergency”. Many celebrated this as a milestone, but due to the complexity surrounding FGM, the ban should not be celebrated too soon.

Politics and FGM

Culturally, Bondo initiations and membership have a threefold meaning symbolizing membership, femininity, and rite of passage, with FGM marking the graduation from training to membership. Initially girls used to spend up to one year in the secluded Bondo Bush learning about womanhood from Soweis (Bondo elders and exisors), however, in the post-civil war period the Bondo Bush social learning process has deteriorated and economic and political power dynamics now overrule traditional aspects (see Bjälkander 2013 and Gruenbaum 2008).

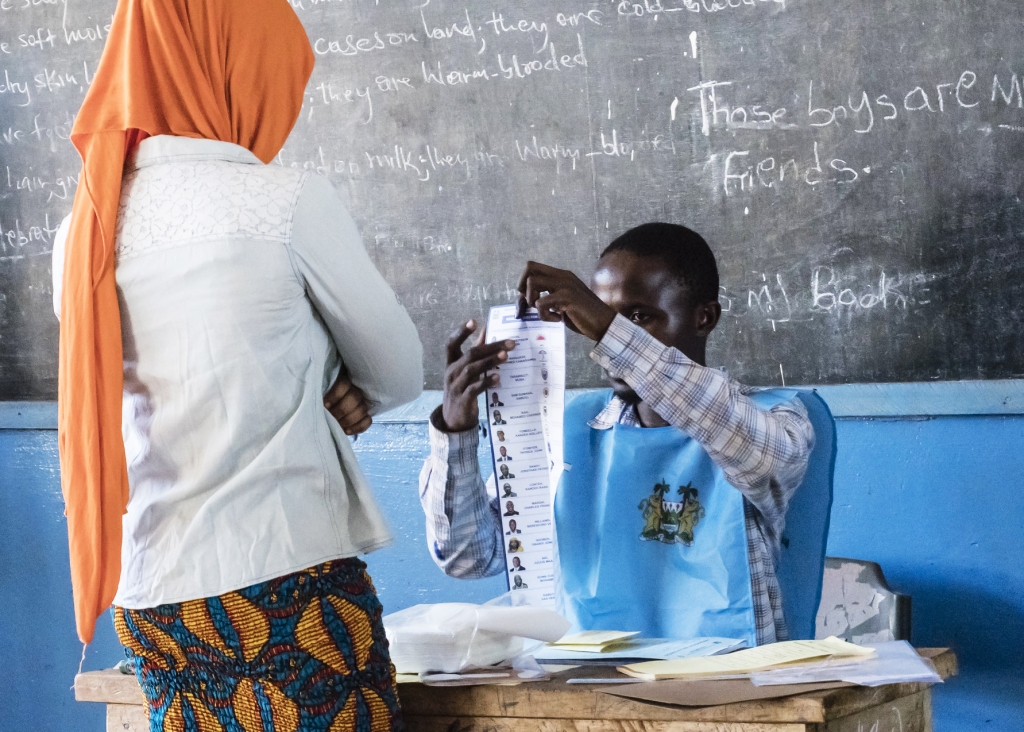

Politically, Soweis are the link between communities and the central government, with the power of influencing the female vote. Economically, initiation fees are shared between local Paramount Chiefs and Soweis, fostering a monetary incentive to maintain FGM. Subsequently, FGM has become a highly politicized issue and politicians at all levels are known to sponsor initiations as a form of vote buying. Speaking out against Bondo is considered political suicide (see Fanthorpe 2007 and Mgbako et al 2010). This political and economic dependence contributes to Sierra Leone remaining one of only six FGM-practicing African countries to without criminal legislation against FGM. It took Sierra Leone until 2015 to ratify the Maputo Protocol and few steps have been taken to enforce it. Furthermore, the domestic Child Rights Act was passed with delay and only after the FGM clause was removed after heated debate in parliament and with all Paramount Chiefs insisting on its removal.

The political debate on banning FGM in Sierra Leone was sparked only five years ago during the outbreak of Ebola. The government issued a temporary ban on Bondo initiations to contain the infection. Subsequently, the “National Strategy for the Reduction of FGM 2016-2020” was drafted but never realized and initiations continued as always. In March 2018, prior to the national election, sponsoring initiations as part of a candidate’s electoral strategy was banned for the first time. Yet, this appeared to be a further use of Sierra Leonean women as political symbols instead of genuine protection.

New Initiation Ban

Last year, President Bio and his wife launched the “Hands Off Our Girls” Campaign, calling for the end of child marriage and sexual violence. No reference was made to FGM, despite a 10-year-old girl bleeding to death during the initiations of 68 girls in December 2018. The anti-sexual violence stance was reinforced with the declaration of rape as a “national emergency” in Sierra Leone in February 2019.

But sexual violence and FGM are linked and mutually reinforcing. Sierra Leonean anti-FGM campaigner Alimatu Dimonekene states: “we cannot address rape and ignore FGM […] FGM is the construct of systems that drive rape and all other forms of sexual violence and abuse of our girls in Sierra Leone”. Childhood initiation and the subsequent marriable status continues to be the reason for nearly 40% of girls being married before the age of 18 and 28% becoming teenage mothers.

Girls continue to endanger their lives in initiations, undergoing FGM in unhygienic conditions, subjected to torturous pain, lifelong trauma and devastating health consequences. So while Sierra Leone’s “Hands Off Our Girls” Campaign and national emergency status will foster dialogue and raise awareness for women’s rights in Sierra Leone, the underlying issues of FGM remain unaddressed.

The new initiation ban needs to be viewed in context. The released statement cites the ban as being a result of “misuse of Secret Societies” accusing members of “using these societies to settle scores with political opponents”. But is this really new? The mutilation of girls for political purposes in Sierra Leone has long been documented. Notably, former President Kabbah’s wife sponsored the initiation of 1,500 girls in the 2002 presidential election. Instead, the new initiation ban comes after economic conflicts between the male Poro Society and large companies. Initiations were banned in order to de-escalate tensions after two men died following a Poro landgrab and the kidnapping of seven men by Poro Society members. It must be emphasized that these were economic struggles and violence with men as perpetrators and men as victims. There was no reference or link to the fatal and traumatic consequences of FGM.

So far, (temporary) bans have only occurred for public health, as an electoral campaigning strategy and now to prevent economic violence. While the government, with its anti-rape and anti-child marriage campaigns, has taken very important steps to implement girls’ rights (!), FGM continues to be unaddressed. There continue to be no laws, trials or convictions against FGM. There is no talk of saving girls’ lives, but rather how to stop political manipulation. FGM must be banned and discussed, not as a secondary cause, but for the prime reason of causing misery and detrimental health. Without the explicit inclusion of an “FGM ban” in national legislation, Sierra Leonean girls are at severe risk to becoming part of the 68 million girls worldwide predicted by UNFPA to be mutilated by 2030.

Johanna Horz is a MSc African Development candidate with professional and research experience on anti-FGM and girls education projects in Sierra Leone.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Hi There,

I am from the Nationa FGM CEntre and interested in having a conversation with Johanna Horz about this blog.

Leethen