Throughout the upcoming week we’ll share top blog posts from this year’s students in Duncan Green’s class on ‘Advocacy, Campaigning and Grassroots activism‘ in which students design a campaign strategy for a cause close to their hearts. First up, Monica Moses on the plight of the sewer cleaners of Mumbai.

See more from the Activism students here.

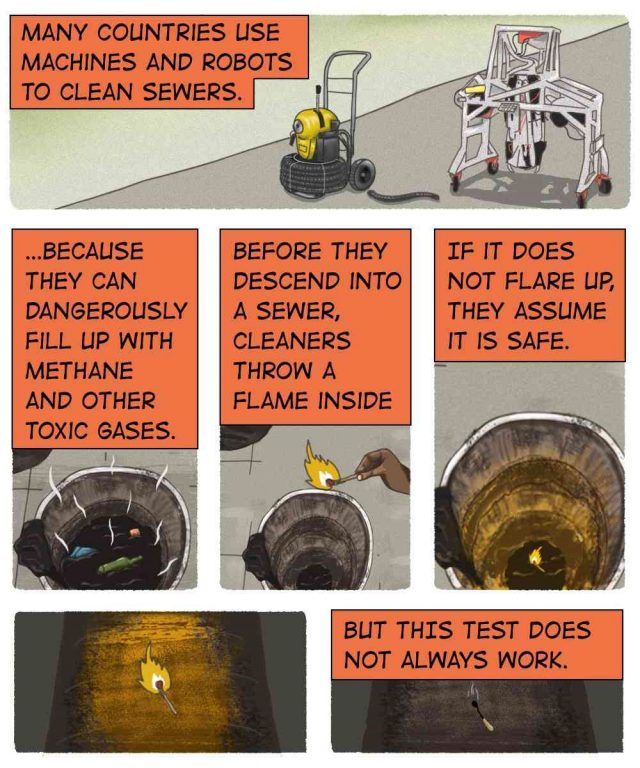

The Indian government has now gained the capacity to destroy satellites in space, but is somehow still unable to prevent the deaths of lower-caste Dalit workers engaged in cleaning sewers.

As citizens of Mumbai, we’ve become accustomed to the annual monsoon floods and always blame the city’s poor sewage infrastructure for these inconveniences. However, we do not give a second thought to those who are tasked with cleaning our sewers in preparation for these floods and throughout the rest of the year. Who cleans our sewers and shit? Who gets killed in this cycle? Whose lives matter to the BMC?

Some Interesting Facts

Mumbai city has the richest municipal corporation in India, is engaged in the construction of an elaborate metro system and coastal road, but still refuses to purchase machines to clean sewers that can save lives. Here’s how you can help hold the BMC accountable through the ‘This Shit is Killing Me’ campaign.

It’s easy to flush out the politics of shit from our daily lives, but this is exactly what this campaign aims to do. It is far too serious an issue to ignore, simply because it does not make for dining table talk. Did you know that more Indians die through manual scavenging than through protecting our borders as soldiers?

What can you do?

Before you panic, let’s make something clear: The citizens of Mumbai are not wholly responsible for deaths caused by this illegal employment of workers. The BMC has been systematically diverting funds away from implementing rehabilitation programmes for safai karmacharis (Sanitation workers) or hiring them on a permanent basis. However, we still have the power to influence the BMC to strictly enforce the provisions made by existing laws for their protection and collectively contribute to restoring dignity to their livelihoods.

Your task is simple- Every time you come across safai karmacharis entering a manhole without any protective gear, click a picture and upload it onto social media, using the hashtag- #ThisShitIsKillingMe.

Political Failures

This publicity before the upcoming elections will definitely shame the BJP, Shiv Sena and Congress, none of whom have addressed this heinous phenomenon in their election manifestos. The Swachh Bharat Abhayan (Clean India Mission) remains ineffective if it neither acknowledges those who are engaged with the groundwork nor the perils they face on a daily basis.

The BMC’s political apathy is most visible by its failure to implement the Prohibition of Employment of Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013- An Act that has provisions for their rehabilitation into alternative careers and promises the mechanisation of their occupation.

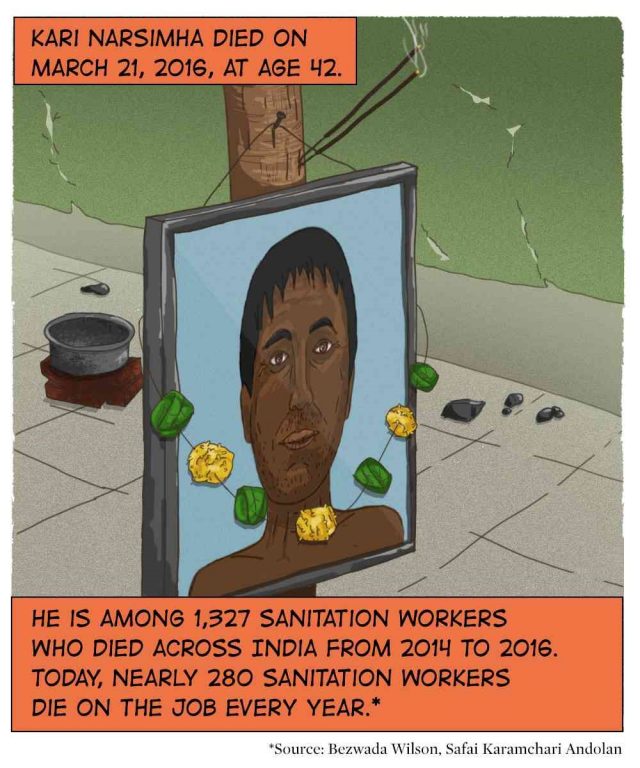

The campaign will be working in collaboration with the Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA), a movement started by sanitation workers, but largely unpopular amongst the citizens of Mumbai and conveniently ignored by the BMC. The social media activism will also contribute to the SKA’s long-term goals, therefore empowering sanitation workers in the process.

With your help, the ‘This Shit is Killing Me’ campaign will draw attention to the inaction of multiple governments at the central, state and municipal levels, in their callous disregard for the deaths caused in manual scavenging. This upcoming elections, remember that who you vote into power will decide the fate of these labourers, the fate of our city’s sewer system and most importantly, whether safai karmacharis in India’s richest city will continue to get killed while cleaning our shit.

Monica Moses is an MSc Development Studies candidate in the Department of International Development with a background in aid, research and advocacy work, along with a strong foundation in social service programs.

This article was first published on the fp2p.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.