On Wednesday 4 March, we invited Deepak Nayyar, Professor of Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, to come to LSE to talk about Asia’s economic transformation over the last fifty years (listen again). International Development students Wingyan and Noman tell us what they took away from the lecture.

I was skeptical about a talk that attempts to review decades of Asian development in 90 minutes. The time constraint meant that Professor Deepak Nayyar could only give a by-section summary of his new book, Resurgent Asia: Diversity in Development. Nevertheless, I walked away with pages of notes that helped me reflect upon the role of macroeconomic policies in development.

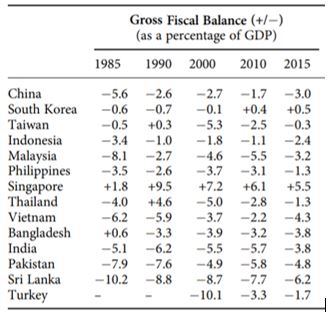

I picked up a comment made by Prof. Nayyar when he was describing Asian countries’ macroeconomic conditions in the past few decades. The Asian-14[1] countries, Prof. Nayyar commented, were heterodox in their policies and did not follow the orthodox prescriptions of balanced budget and price stability. Their primary macroeconomic objective was economic growth and, in some, employment creation. This comment is contrary to my impression of Asian countries being prudent with high savings rate. In fact, when I looked at the data provided by Prof. Nayyar in his book, I found that the Asian-14 mostly ran a fiscal deficit during 1985-2015, with the notable exception of Singapore which had a fiscal surplus throughout the period.

The pre-Asian-financial-crisis deficits in 1990s were even higher than the Latin American average of around 1-2% before the 1980s fiscal crisis[2]. Although both regions were subsequently hit by a financial crisis, Asian countries clearly recovered faster than Latin America. Southeast Asia, the epicenter of the crisis, had an average annual GDP growth rate of 4.41% during 1981-2000[3], way above Latin America’s average of 0.5% during 1981-2002[4].

From Prof. Nayyar’s lecture, one would probably attribute the divergence between the two regions partly to the use of government expenditure. While Latin American governments spent a lot on subsidizing domestic firms under the import substitution industrialization policy, Asian governments mostly spent on countercyclical policies to stimulate local firms during economic downturn. Because of Asian countries’ use of fiscal and monetary policies to encourage economic growth without being obsessed about inflation or budget deficit, Prof. Nayyar called this policy “heterodox”.

I am surprised he called this “heterodox” as I thought government had often adopted economic stimuli without fully considering their macro consequences. From Keynes’ interventionist advocacy during the Great Depression to Britain’s wave of nationalization before the 1980s, I do not think price stability has been an “orthodox fetishism” as Prof. Nayyar puts it. This might be true for modern Germany or other European countries afflicted by runaway inflations (e.g. Hungary) after World War II. I do think, however, that high savings rate is quite distinctly Asian – especially in China with the absence of a social safety net and financial repression.

Much of the government expenditure is also on education, which Prof. Nayyar saw as a main driver of growth in Asia. Regrettably, Prof. Nayyar never explained why Asian countries differ in education investment. Since skill-biased technological change is bound to create more inequality, we need to understand and address the challenges that are stopping countries from investing in education.

While sound macroeconomic fundamentals are essential to a country’s development success, Prof. Nayyar repeatedly stressed the challenge of inequality facing many Asian countries. As a student in local economic development, I believe this is where policy should change from focusing on interest rates and tax to focusing on space and community.

[1] The 14 countries Prof. Nayyar chose to base his book on. They are China, South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Turkey

[2] Ocampo, Jose Antonio. “The Latin American Debt Crisis in Historical Perspective.” Unpublished Manuscript (Columbia University), 2013.

[3] Nayyar, Deepak. Resurgent Asia : Diversity in Development, 61. First ed. Oxford Scholarship Online. 2019.

[4] Solimano, Andrés, and Raimundo Soto. Economic growth in Latin America in the late 20th century: evidence and interpretation. Vol. 33. United Nations Publications, 2005.

Wingyan Yip is a MSc Local Economic Development student at LSE with a bachelor’s degree from Yale-NUS College in Singapore. Wingyan is passionate about the political economy of Latin America and Asia, as well as data science and machine learning.

__________________________________________

An insightful talk on Asian Economic Transformation was held at LSE on March 4, 2020. The talk was delivered by none other than the eminent economist of time Professor Deepak Nayyar, Emeritus Professor of Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and an Honorary Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. Professor Nayyar started his talk with anecdotes on historical and cultural milieu of Asian heritage only to plunge into the discussion on phenomenal economic transformation of Asia. He finely interlinked the cultural diversity of Asia with the critical issues of development perspectives.

The colonial era marked the decline of Asia. According to Professor Nayyar, the de-industrialization of Asia and the industrialization of Europe are two sides of the same coin. The pre-colonial Asia was well structured in culture and power. Asia used to share almost 70% of world GDP in 1820s which gradually declined during the colonial era. The growth of Asia started with the political independence of the corresponding countries. Although East Asia was leader in this growth South Asia seemed to be a laggard. Gradually the democratic government put more emphasis on health, education and foreign investment. Although there was no silver bullet of development recipe the rise of Asia can be discernible, as Nayyar proposed. The foreign investment created a healthy domestic market (Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore etc.) and infrastructure accelerated accordingly. The shift from agriculture to industry and then to services is another noteworthy leap for the Asian giants to mark its territory in the growth race. But Professor Nayyar also viewed these three sectors equally important for a sustainable growth. Economic transformation cannot work if any of these three is a ‘weakling’. Along with the labour exit from agriculture to services Professor Nayyar pointed out the crucial effect of economic openness of a country. Quoting his newly published book Resurgent Asia, he suggested that economic openness is conducive when followed by a sound industrial policy. Answering a question by Professor James Putzel, Nayyar drew a comparison between the growth of China and India. China maintained a rigorous industrial policy while India never adopted any.

While talking on the political aspects of development, Professor Nayyar found democracy to be a better option for development as it has self-corrective measures. According to him democracy is evolving slowly and in a healthy democracy state and market complement each other. Though there is a rising inequality worldwide Nayyar would like to call himself a ‘cautious optimist’. He believes that the growth of Asia will sustain for the next 25 years uninterrupted. He also implied his concern over the recent outbreak of Covid-19 Virus in hampering China’s and other economies.

The session was a spontaneous one. There were rounds of questions and queries which the distinguished guest answered astutely. It was indeed a prolific thought sharing evening.

Arafat Mohammad Noman is a Bangladeshi bureaucrat who is pursuing his MSc in Development Studies at LSE. His interests rest in politics, gender, culture, race, digital humanism and so on. Reach Arafat Noman at A.Noman@lse.ac.uk.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.