On Friday 11 December Danny Quah gave an online lecture, ‘Global Power Shift to Asia: Great Power Competition in the Marketplace for World Order’ as part of the Cutting Edge Issues in Development Lecture series. Danny Quah is Li Ka Shing Professor in Economics at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. Read what Development Studies MSc student Juhi Chanchalani took away from the lecture below.

You can watch the guest lecture back on YouTube.

World Order – a phrase used to describe the power dynamics that govern relationships between countries – is a highly debated concept in the fields of international development and international relations. Whether you are for or against it, you can’t deny it characterises every policy decision taken in the realm of international affairs. In recent times, there has been rising discontent with the prevailing World Order, expressed by both the architects, and the recipient countries, of this system.

Overcoming technological challenges, Danny Quah, professor in Economics at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, revisited LSE’s digital space to deliver his views on the dynamics of the current World Order and competition between great powers. Speaking to students and alumni of the Department of International Development, and a wider YouTube audience, Quah argued that not only is the traditional view of a linear, hierarchical, unipolar world order a dated one, but also that the existence of a World Order is not necessarily bad. Instead, he argues, as a system, the World Order has proven to be quite beneficial, and therefore should be retained but reimagined as a marketplace, with suppliers and consumers of development benefits.

Over the last 70 years, observers, scholars and historians have described the dominant World Order as a vertical, linear hierarchy, organised around the United States as a unipolar centre. Scholars like Chang and Wade have argued that this dominant system did not allow for equitable growth around the world. In fact, they argued that it was a system created by the rich that works for the rich, with the intent of “kicking away the ladder”. Recently, there has been growing discontent with the World Order within the creator of the system as well, expressed by President Trump, who has criticized the system for placing excessive political and financial burden of governance on the United States, while allowing for prevalence of unfair economic practices by rapidly growing countries like China.

In his hour-long talk, Quah examined past rhetoric and economic evidence to argue that the World Order was not a sinister consideration and to a large degree, achieved what it envisioned. He argued that the system was guided by benevolent intentions of a “one world” vision that aimed for global interaction on a level playing field, and the past 4 decades have seen increasing evidence of convergence amongst states. At the risk of sounding like an apologist for the west-dominated system, Quah termed the United States a “benevolent hegemon”. But Quah also acknowledged that the current system was not perfect. However, instead of seeking to do away with the current world order, he suggested a rethinking of the system as a marketplace of supply and demand, where some countries were suppliers, and others consumers, of development.

Quah advised Development practitioners to think of the World Order system beyond the idea of geostrategic conflicts, geopolitical power struggles and rivalry, to a marketplace system where great powers were suppliers of global public goods, seeking admiration and alliance from smaller countries who formed the demand curve. Further, he claimed that the fall of the American hegemony over the last decade, as a result of the 2008 financial crisis and COVID-19 mismanagement, created an opportunity that allowed smaller powers to demand better governance practices, and hold suppliers of development accountable.

Quah’s views sparked a spirited debate between him and discussant Robert Wade, professor of Global Political Economy at the LSE and a heterodox political economist. Quah stated that realistically, some countries are not big or strong enough to provide public goods to the world, and will therefore always be consumers of the world order. However, Wade argued that the status quo was a result of the world order that trapped countries within low-income production activities, limiting their growth potential. Further, although combined GDPs may have increased across the decades, very few developing countries, with the exception of China, have moved from low and middle-income brackets, as defined by the World Bank, to become high-income countries. Finally, the same system that allowed for the rise of China had also worsened inequalities within countries and between countries.

This lecture certainly left me with probing thoughts and questions. If arguments that the current discontentment of the US leadership with the world order is a result of their thwarted hegemonic ambitions (due to the rise of China) are to be acknowledged, then it stands to reason that political power is in the driving seat of motivations that govern world order system design. Further, while the existing world order may have its benefits and flaws, does Quah’s reimagined system minimize the ambition within the field of development that consumers could eventually become suppliers within the world order? Does the world need a new system of organized governance, given failures of the current system? Guess I’ll continue studying my degree to find out!

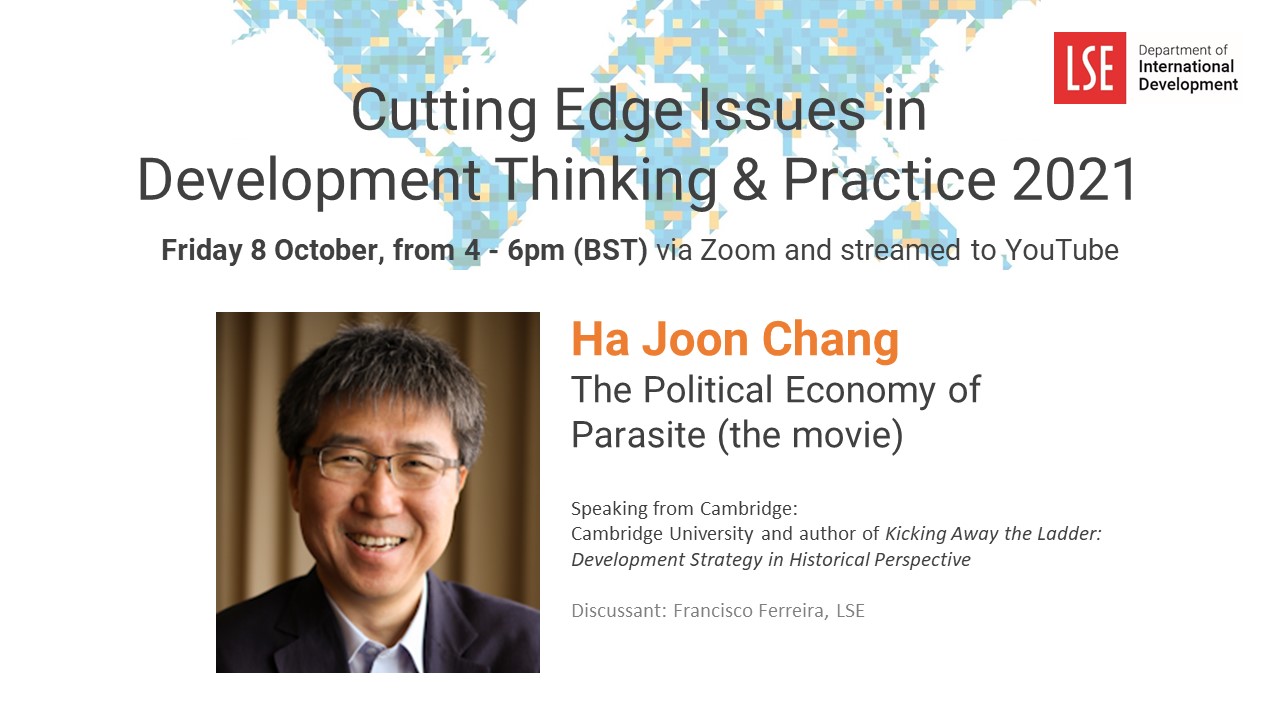

This next lecture in the Cutting Edge Issues series will take place from 4-6pm (GMT) this Friday 22 January. Ha-Joon Chang will be joining us from Cambridge to give a lecture on ‘Building Pro-Developmental Multilateralism – Towards a ‘New’ New International Economic Order’. LSE staff and students can sign up for the lecture here and external audiences can join the lecture via YouTube.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.