MSc Development Management student Satender Rana proposes a conceptual framework to unravel gender dynamics in food systems and argues for the importance of addressing gender inequalities to develop efficient, inclusive and resilient food systems.

Food systems encompass the entire value chain including production, processing, transportation, distribution, and consumption of food. According to the CGIAR, of the many actors involved in food systems, women are one of the key stakeholders. In fact, during the last two decades, agriculture has been feminized as the waning economic incentives in farming across developing countries pushed men to migrate to cities in search of new livelihood options. Now women are at the forefront in agriculture and allied sectors. Therefore, their role has become ever more important to ensure sustainability of food systems, and food security.

However, women continue to face constraints including lack of ownership of land, access to improved technology and productive resources as well as discrimination in credit and labour markets which, coupled with social norms, hamper their productivity and economic potential. Gender discrimination has severe negative implications for agricultural productivity and food systems, considering that about one fourth of the agricultural labourers in the developing world are women. Also, the world population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 implying greater food demand. Thus, to meet this growing food demand and make the food systems efficient, inclusive, resilient empowerment of women in food systems is indispensable. Strengthening women’s role in food systems entails a deeper understanding of gender interactions and how they interplay in food systems, because the role of women in agriculture and allied areas is heavily affected by gender norms. Therefore, the knowledge of how gender interacts and interplays in food systems is vital to develop policy and programmes to make gender interactions favourable to women’s participation and productivity in agriculture, and food systems. To unravel gender dynamics in food systems, this essay describes a conceptual framework based on the value chain model of Porter & Kramer.

The Conceptual Framework

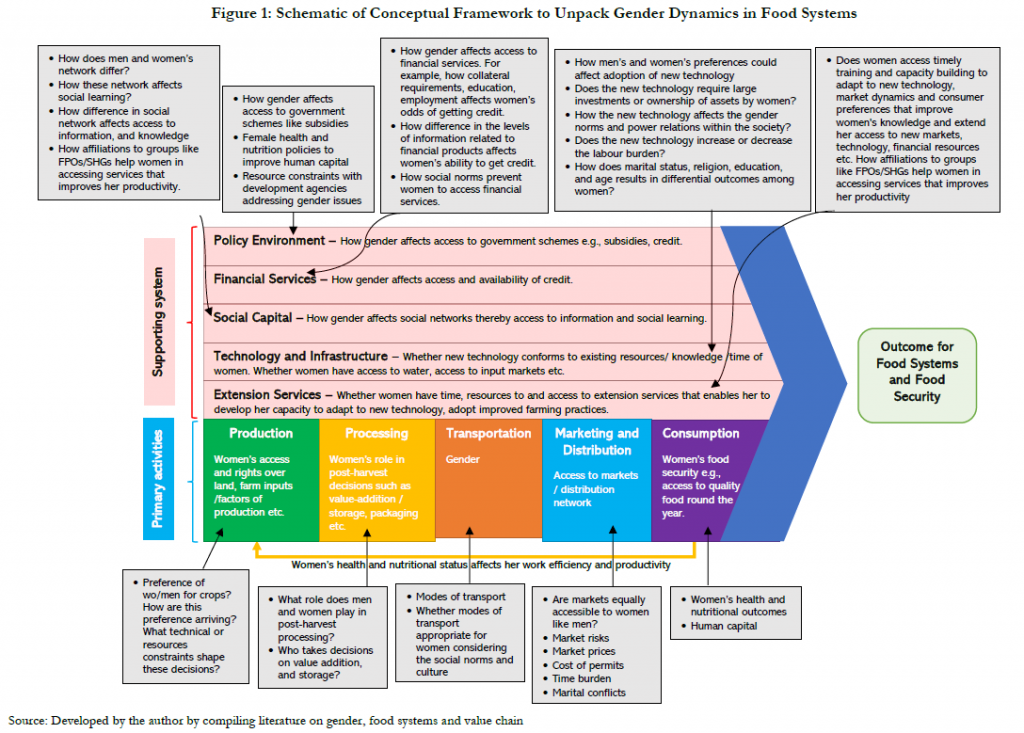

Depicted in Figure 1, the framework attempts to disentangle interrelatedness of gender dynamics and food systems. The framework is helpful in charting the consequences of gender dimensions at each stage of food systems. It can be an effective tool in identifying and prioritizing key areas to address gender issues which poses a threat to sustainability of food systems and making the food systems’ value chain resilient and responsive to the growing food demand.

The framework is based on literature available on gender, agriculture, and food systems (CGIAR; de Pryck & Termine; Doss; Fletschner & Kenney; Quisumbing et al.; Quisumbing & Pandolfelli) and the value chain model of Porter & Kramer. It identifies nine key activities that constitute the food systems. These activities are bifurcated into primary and support activities. Primary activities are those on which a household can make its own decision while the secondary activities involve actors from outside the household. Although the activities are bifurcated into two parts for simplification, the framework is one integral system where each activity relates to all other activities.

Primary Activities

As depicted in Figure 1, the primary activities comprise production, processing, transportation, marketing and distribution, and consumption. How gender dynamics interplay with each of these stages would be helpful in identifying specific gender issues that affects the progressive stages as well as the outcomes for the overall food systems.

Production

This stage in the food systems illuminates gender inequalities in decision making with respect to the type of crop, livestock rearing, and constraints women face in making these decisions etc.

Processing

This stage unravels gender roles in decisions over these aspects and whether gender appropriate technology and resources are available for post-harvest processing. It sheds light on the role of women in post-harvest processing and constraints faced by them in making these decisions.

Transportation

Generally, men are at the forefront of managing and dealing with the transportation system in developing countries. Availability and modes of transportation, therefore, may not be appropriate for women considering the cultural and social context. How gender and social norms affect access to transportation can be analysed at this stage of food systems.

Marketing and Distribution

Accessing markets can be specifically challenging for women. In general, the buyers of farmers’ produce consider men to be the primary farmer in the households and are more willing to make contracts with men and generally approach men for agreements. Therefore, this dimension highlights how gender bias creates barriers to women in accessing markets.

Consumption

Women’s food security within the household is essential for food systems. Poor nutrition and health reduce labour productivity. Therefore, high levels of human capital entail availability of quality food to women. This dimension explains how gender norms affect women’s health and nutrition within the household thereby their overall productivity.

Support Activities

The support activities inform about how well women’s rights are protected, their accessibility to resources, affiliation to social networks, and whether an enabling environment exists for them to flourish in food systems.

Regulatory Environment

The policy environment may affect men and women differentially. For example, to avail of government credit from formal financial institutions a farmer might be required to prove the status of being a farmer through specific documentation like ownership of agricultural land. As most of the women in developing countries lack ownership of land, they may remain deprived of access to formal financial institutions and government schemes. This could severely hamper their capacity to adopt new technology, ability to use better agricultural inputs etc.

Financial Services

Availability of finance has also been cited as a huge bottleneck which stifles women’s capacity in agriculture. Some authors have suggested that the inclusion of “softer” assessment criteria than the traditional ones in connection with lending to women. Women’s personal savings constitute between 80% and 99% of initial capitalisation, compared to men where the figure is between 30% and 59%. Another impediment to entrepreneurial capacity is the masculine mentality in the banking industry. Women enter an environment constructed by men; therefore, they may be perceived as less legitimate in the eyes of prospective financial backers.

Social Capital

Social learning is rooted in an intricate web of social networks. Networking is vital in enabling people to access information about markets and suppliers. However, women face greater challenges in accessing this information because they have less time for attending events and group meetings. This perspective suggests that the performance of women in agriculture is influenced by the presence or absence of networks, such as membership in organizations, which is crucial for the sustainability of rural livelihoods. However, certain divisions and constraints can limit women’s access to networks, which can have significant consequences for their performance in agriculture.

Technology

Inability to obtain loan/credit against collateral due to lack of ownership of assets affects women’s ability to adopt new technologies. On the other hand, technology itself may not conform to the socio-economic realities of women. It is reported that technology could be gender discriminatory if it increases the time burden, mismatches with existing skills, requires large investment, or is not culturally permissible to women.

Extension services

A lack of relevant skills and knowledge constrains growth potential. This is compounded by deficiencies in basic education. Gaining relevant skills and knowledge also can be more difficult for women since their double work burden and childcare responsibilities make them less able to attend formal and informal training than men. Thus, extension activities can unveil the gender differences in access to necessary training and acquisition of the skill sets required to adopt technology, improve farming practices. It can also explain how social norms affect women’s access to and participation in extension programmes.

The framework captures specific challenges because of societal stereotypes combined with unfavourable cultural, economic, technological, and regulatory environments that have implications for women’s participation and productivity in agriculture. The advantage of the model is that it can be used across different contexts as it uses a basic value chain framework which maps gender interactions across different phases involved in food systems.

However, the framework does not account for the effects of climate change which have severe negative implications for both gender dynamics and food systems. For example, exhaustion of nearby resources such as depletion of water resources and shrinking forest land have doubled women’s time burden. They spend more time in fetching water or fuel and thus have less time to spend in agriculture fields or taking care of cattle. It might also affect their household interactions and gender relations as they spend less time in the households. Also, lack of ownership over assets means women are unable to avail credit against a collateral to manage climate shocks. Thus, for taking a holistic view of gender dynamics and its implications for the food systems, other dimensions like climate issues must also be considered

Despite some limitations, the framework provides a good starting point to map gender interactions and how they affect food systems. It can be used to identify and prioritize gender issues to increase women’s participation and productivity in agriculture and allied activities and to develop resilient food systems which is more responsive to gender needs and growing food demand.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Photo credit: Satender Rana, Image of farm workers in Odisha, India.