PhD student in LSE Department of Government Meshal Abdulaziz Alkhowaiter draws from recent data sets to argue that introducing a private sector minimum wage in Saudi Arabia would significantly reduce income inequality and unemployment.

The International Labour Organization (ILO)’s latest Global Wage report shows that around 90% of ILO member countries have adopted one of two major types of minimum wage regulations: those negotiated through collective-bargaining and statutory minimum wage laws set by governments. I will argue here that introducing a minimum wage for all private sector workers in Saudi Arabia can have substantial economic benefits, namely: reducing unemployment rate amongst its citizens and global income inequality. The ILO’s definition of the minimum wage refers to a wage floor (i.e. minimum monetary amount) that each worker is guaranteed to receive in a given period. Furthermore, countries that strictly have a minimum wage for public sector, but not private sector employees are not classified as having a minimum wage (e.g. Egypt and Saudi Arabia).

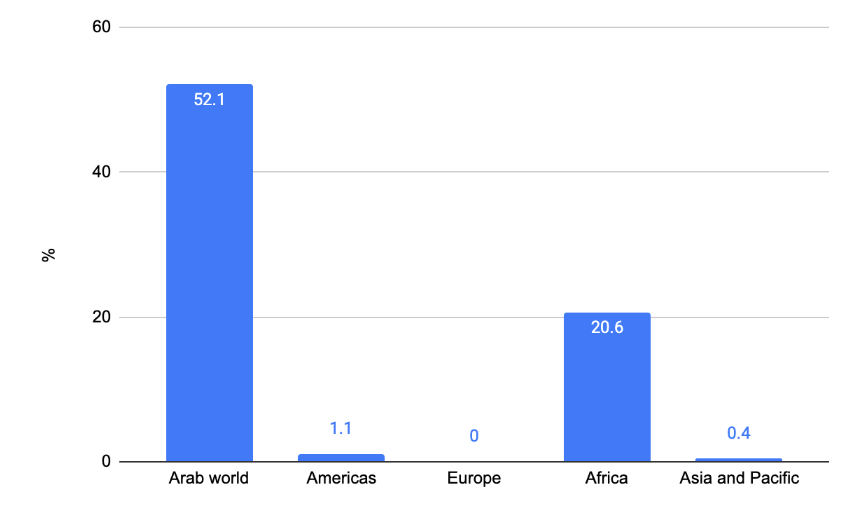

Additionally, I will further center my discussion here on minimum wage laws in the Arab world, given how widespread it is for workers not to be covered by any wage floor at 52.1%, compared to other regions across the world. However, I will further focus my analysis here on Saudi Arabia for four main reasons. First, remittance outflows from Saudi Arabia by foreign labour, were the third highest in the world in 2020 at $34.6 billion, according to the World Bank’s latest remittances data. Second, the country’s private sector is one of the largest in the Arab world at 8.1 million workers, and also employed 6.023 million foreign workers, as of Q3, 2021. Third, unlike some Arab countries that impose a minimum wage for their citizens, both Saudi workers, and foreign workers, are not covered by a private sector minimum wage in Saudi Arabia.1 Lastly, unlike its neighboring Arabian Gulf countries, Saudi Arabia has a serious unemployment problem amongst its citizens at 11.3%, and particularly educated women, which lack of a minimum wage is exacerbating as I will explain later.2

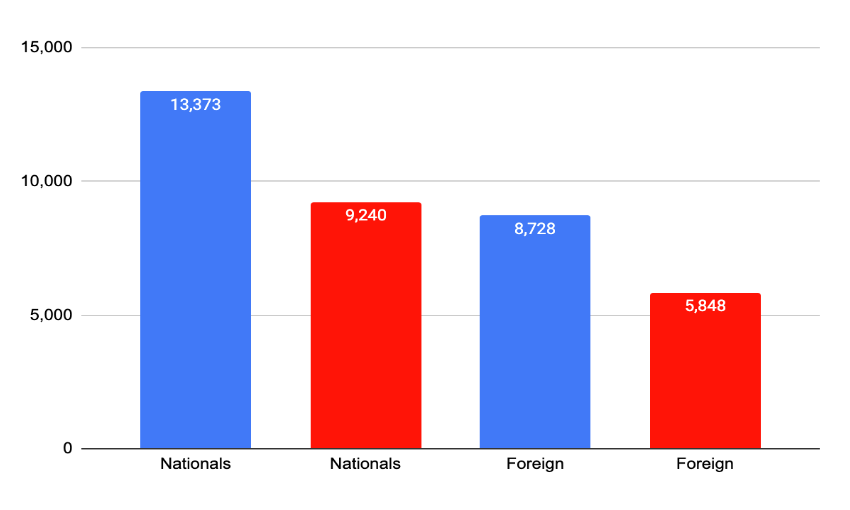

While the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development requires private firms to pay citizens a minimum of 4K Riyals per month to count nationals for Nitaqat program purposes (i.e. nationalization hiring quotas in the private sector). However, private firms can still pay citizens below the 4K Riyals amount. For instance, according to Q3, 2021 administrative data, nearly 10% of Saudi private sector workers earned below earned 4,000 Riyals. Private employers have even greater power to pay foreign workers below 4K Riyals/month as they are neither statutorily required nor are they obliged by Nitaqat program regulations. As a result, about 83% of foreign labour are paid less than 4K Riyals/month by private firms.10

Introducing a minimum wage to global income inequality and cut domestic unemployment

Saudi Arabia currently employs millions of foreign workers (e.g. 2.5 million workers from India alone), and thus contributes to reducing the global unemployment rate, as many low-skilled migrant labour in Saudi Arabia would have been jobless or earning significantly less in their home countries.

However, given the magnitude of outflows by foreign workers from Saudi Arabia at $34.5 billion per year, I argue that imposing a minimum wage for all private sector workers has the potential to even reduce global income inequality, which are highly correlated (i.e. the existence of a minimum wage and income inequality).3 To demonstrate this likely impact on how a minimum wage reduces global income inequality, let’s take the example of low-income foreign labour in Saudi Arabia. Currently, there are around 3.46 million foreign workers earning less than 1,500 Riyals/month, and if a national minimum wage is introduced at 3K Riyals, remittance outflows from Saudi Arabia would increase drastically, thus helping to further fight poverty in their home countries and reduce overall global inequality.4

I argued earlier that introducing a minimum wage can also reduce the unemployment rate amongst Saudis, which might appear puzzling at first. However, numerous studies on Saudi Arabia’s labour market such as Hertog (2012) and the IMF (2018), suggest that the private sector wage gap between national and foreign workers can negatively impact the chances of citizens in private sector employment. This occurs intuitively because when a private firm must decide between hiring two workers with equal qualifications, it will likely hire the worker who has a weaker bargaining power and less labour protections (i.e. a foreign worker in Saudi Arabia). I control for educational attainment to show that even with equal qualifications, foreign workers can be paid less, which makes them a more attractive option to hire for private firms. This peculiarity in turn leads to more unemployment amongst Saudis as they compete against cheaper foreign labour (i.e., as evinced by average salaries below) who are easier to fire from an employer’s perspective.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I believe that introducing a minimum wage for all private sector workers in Saudi Arabia can not only improve earnings for impacted workers but will also have positive spillover effects, both within and outside of Saudi Arabia. Within Saudi Arabia, such a policy would give greater labour protections for foreign labour, and will eliminate the cost-disadvantage that citizens currently experience in the workforce, thus making them more “employable.” In other words, when both costs and qualifications are equal, private firms will hire individuals based on merit, not on ease of exploitation. Finally, Saudi Arabia already employs millions of low-skill foreign labour who could not find better jobs in their home countries, but by instituting a national and uniform minimum wage, Saudi Arabia could contribute to a sizable reduction in global poverty and income inequality.

1The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development requires private firms to pay citizens a minimum of 4,000 Riyals/month to count nationals for Nitaqat program purposes (i.e. nationalization quotas in the private sector). However, private firms can still pay citizens below the 4K Riyals amount.

2Unemployment data from LFS Q2 2021 shows that 61.1% of overall unemployed Saudi women, held a Bachelor’s degree:

https://www.stats.gov.sa/ar/814.

3Numerous studies empirically prove that introducing a minimum wage has a positive impact and reduces income inequality and poverty, see Cornia (2012), Lin and Yun (2016), and

Creedy and Gemmell (2019).

4This assumes that private firms will not respond to a minimum wage by automating the jobs of low-income workers, which is an assumption warranted by recent empirical studies on automation and the minimum wage. Ex:

https://www.ft.com/content/8ca82482-2564-11e9-b329-c7e6ceb5ffdf.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Photo credit: The International Labour Organisation, 2010 via Flickr.