MSc Environment and Development student, Li Xuan Tan tells us about how smallholders in Sabah, Borneo, are transitioning to sustainable palm oil production with the support of NGOs. This article is a companion piece to another article by Li Xuan from January 2022: ‘The palm oil problem: There can be no sustainable development without indigenous participation‘.

Palm oil is a major export commodity for Sabah. The state – located in northern Borneo – has the highest output in Malaysia, which is the world’s second-largest producer after Indonesia.

Sabah produced over four million tonnes of crude palm oil in 2020, with an estimated revenue of $3.4B. Palm oil constitutes a large chunk of the state’s GDP and most of its agricultural output. This comes as no surprise, as its total palm oil planted area exceeds 1.54M hectares, of which approximately 26% is certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

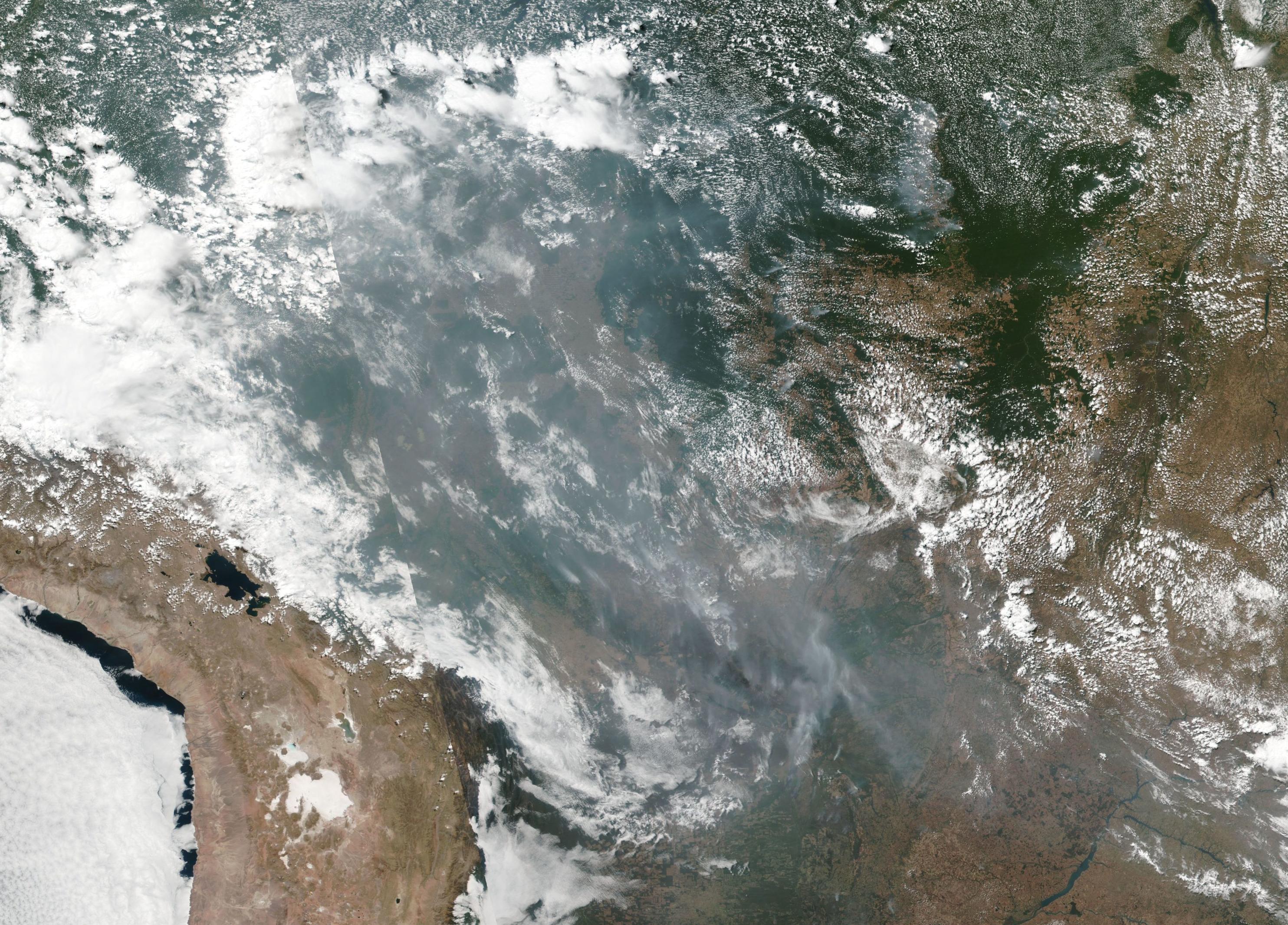

This accounts for 10% of the world’s annual production, thus contributing to extensive deforestation practices. According to Global Forest Watch, Sabah lost approximately 339,000 ha of its natural forests between 2002 to 2020.

The problem with boycotting

Despite increasing international calls to boycott the industry, indigenous peoples – who constitute a substantial portion of Sabah’s palm oil smallholders – have been ignored. Excluding these voices from such drastic decisions is counter-productive and only serves to alienate communities.

Palm oil is an important source of income for an estimated 53,000 smallholders state-wide, a figure which led the state government to commit to a 10-year policy initiative back in 2015.

Through JCSPO – The Jurisdictional Certification of Sustainable Palm Oil – it pledged to produce 100% RSPO certified palm oil. This incentivised companies with existing initiatives to align sustainability and development targets across Sabah.

The industry’s answer has been to formulate the RSPO, a multi-stakeholder body fostering collaboration between industry and the WWF.

The RSPO aims to improve corporate responsibility whilst also pursuing greater legitimisation of continued expansion.

The RSPO aims to accomplish zero-loss of High Conservation Value and High Carbon Stock forests within Sabah’s entire palm oil production, facilitating zero-conflict environments. They are also working to improve smallholder sustainability and empower local livelihoods by 2025. To date, about 26% of palm oil produced in Sabah is RSPO-certified.

Towards sustainable palm oil

Sophia Lim, Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer of WWF-Malaysia, sees this as:

“a crucial step in positioning Sabah and laying the foundation for the state as the global leader in sustainable palm oil.”

Continued pressure by social justice NGOs has guaranteed that RSPO standards are consistent with international human rights laws, whilst companies are independently audited by accredited certification bodies.

Through training programmes and published guidance, the RSPO has affirmed the rights of indigenous peoples to their customary lands, and no lands can be taken from their local communities without their free, prior, and informed consent.

Its Certification Protocol adoption mandates companies with certified mills and estates to warrant that associated scheme smallholders are also certified within three years.

Moreover, RSPO members must endorse a Code of Conduct, which requires them to uphold these standards while a grievance mechanism provides recourse for those who believe RSPO members are violating the code and a dispute resolution facility is also under development.

To enhance greater smallholder inclusivity, the RSPO has promoted support through a specialised fund, and is creating a separate Independent Smallholder Standard and certification framework that examines the reality of their needs.

The next step: certifications

The initiative was also strengthened through the mandatory Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) national certification scheme in December 2019, as it engaged producers yet to be aware of these sustainability standards and provided a platform for dialogue and assistance towards a common goal.

Increasing yields may increase smallholder’s incomes temporarily, but to improve their livelihoods long-term, the industry must link them to certification schemes. These will enable them to recover the sustainability premium, whilst securing steady access to high-quality seedlings, fertiliser, farming advice and financial capital.

Reza Azmi of Wild Asia acknowledges that some agricultural methods may sound foreign to industrial-scale plantations. These include low-input, low output farming methods – that reduce costs while increasing ground cover – and composting which improves soil fertility and increases the volume of groundwater available to crops.

Furthermore, increasing crop diversity could improve soil health and yields, while also providing alternative income sources when smallholders face cash shortages during the initial production gap after replanting.

In implementing its ‘No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation’ commitments across supply chains, several companies have been investing in smallholder capacity building programmes.

Since 2016, a smallholder project led by NGO Forever Sabah in the districts of Tongod, Telupid, Beluran and Kinabatangan identified smallholder challenges in achieving RSPO and MSPO certification, specifically: poor yields, low technical expertise, and land tenure insecurity.

Similarly, in the Beluran, Kinabatangan and Lahad Datu districts, Earthworm Foundation – with the support of Reckitt, Nestle, ADM Cares, Givaudan, Groupe Rocher and IJM Plantations – collaborated closely with the local government, mills, and producers.

Collectively, they encouraged 200 smallholders to move towards sustainable practices which have improved livelihoods and promoted entrepreneurship.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

This article was first published on: Ours to Save

Image credit: Wikipedia Commons/Uwe Aranas