PhD student Martin Haus and guest blogger Abhinav Ghosh question whether the push for foundational numeracy and literacy in the Indian education system is pro-poor.

The National Education Policy (NEP) in 2020 prioritizes the attainment of foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) for all children in India as an “urgent national mission”. Subsequent guidelines for the same were laid out in India’s Ministry of Education’s NIPUN Bharat program in 2021. While to many, this might seem to be an objectively ‘good’ reform, its framing and operationalization entail several issues that need scrutiny. FLN is broadly conceptualized as a child’s ability to read ‘basic’ texts and solve ‘basic’ math problems (such as addition and subtraction). Despite the rhetoric of “FLN for all”, the push for attaining these basic skills is almost exclusively directed at children from rural and marginalized communities who have historically received substandard education.

Reinforcing what we want to overcome

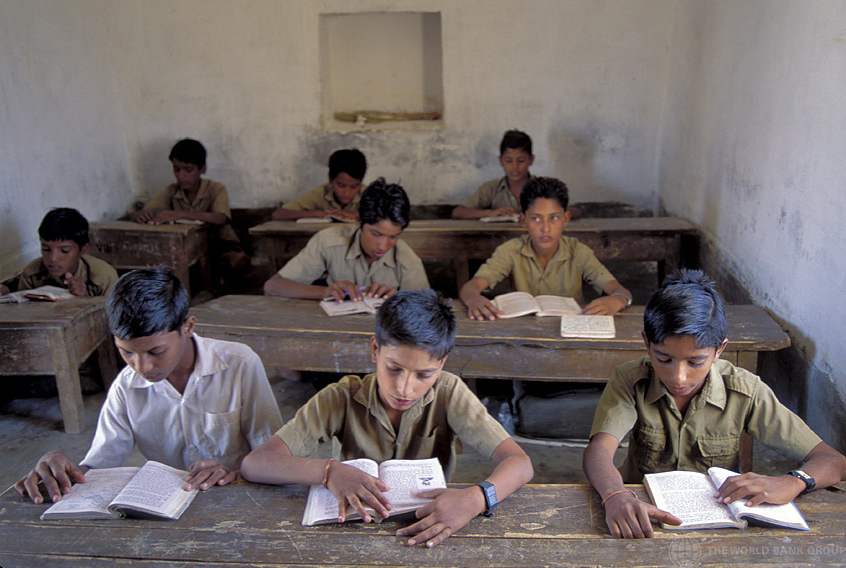

For a long time, rote-learning has been seen as the core problem in the Indian education system. De-contextualized repetition of facts, reciting without questioning, and a general lack of critical thinking have rightly been identified as impediments to holistic forms of learning. Some attempts have been made to introduce elements around critical thinking into classrooms, but this has never happened on scale, also because teachers remain unprepared for this task given their own socialization in rote-learning. A monitoring system that judges performance based on FLN mastery will likely lead to states and schools intensifying rote-learning to avoid “bad results”. It is exactly this fear of failing in standardised assessments that perpetuates rote-learning and paves the way for ‘teaching to the test’ – where teaching, resources, and time are all redirected away from learning towards mere assessment mastery. Contrary to popular belief, the problem of learning historically has not just been pedagogical, but also tied to what has been taught. Today, publicity material for FLN programs often include ‘feel-good’ visuals of students learning mathematics through colourful props or reading books with rapt attention. What these images do not capture is what they are learning. Despite the rhetoric around FLN ushering in quality learning, a singular focus on its mastery oftentimes results in decontextualized mathematical learning (e.g., adding numbers correctly, but without knowing why they are being added or in what setting) and reading without critical engagement (e.g., reading a story fluently but without thinking about how it might relate to their lives or society). Such restrictive goals of learning have historically been barriers to any kind of true innovation in classroom instruction.

A doubtful framing

The word “foundational” implies that certain aspects of numeracy and literacy must come first before any other learning can happen. We question the assumption that without mastering these basic skills, any subsequent education is impossible. Every good education system also ensures numeracy and literacy, but without making them its single or primary purpose. A single-minded focus on these basics, as we outlined above, comes with the inherent risk of decontextualized and rote learning. But even worse, it implies that richer learning and critical thinking come afterwards. Yet, they are not distinct elements in a sequence, but must happen in parallel. Reading without questioning and calculating without understanding its relevance are not quite the foundations for any possible critical thinking but might even lead away from it. We must overcome this misconceived sequential understanding to make our education system ready for the 21st century. And importantly, children also do not want to spend several years mastering FLN to pass a test. They want an education.

Despite claims of how FLN is a goal for ‘all’ children, its prioritization is almost exclusively meant to be for children from rural and marginalized backgrounds – who are already seen as ‘behind’ their privileged counterparts. As such, two separate tracks are reinforced within Indian education – children in elite and high-fee private schools get to focus on rich and holistic content with a focus on higher-order skills such as critical thinking and creative problem-solving. Marginalized children in low-fee private schools and public schools, who are shown to lack these so-called ‘foundational skills’, are expected to first master them before anything else. These distinct learning experiences present significant long-term implications – with some children emerging from K-12 education as ‘highly skilled’ and ‘more suited for elite professions’, and others relegated to being just ‘literate’ and thus facing a limited pool of low-earning professions to be eligible for. Seen this way, it is necessary to question the supposed ‘pro-poor’ flag that FLN bears, especially given the reproduction of social inequity that its prioritization might result in.

Everybody’s darling? How FLN fits into a broader policy agenda

Advocates for FLN frame their pro-‘poor’ agenda through narratives about how “the poor are going to school, but not learning.” Subsequently, they assert that the prioritization of FLN will ensure that the ‘poor’ finally learn in schools. FLN, thus, is positioned as the primary antidote to all learning problems of the marginalized. Above we had outlined some doubts about this narrative, but it is also worth looking at the broader policy agenda. The push for FLN does not happen in a vacuum. In parallel, standardized assessment systems are established that have baked FLN into their evaluative apparatus: good education has now become education that scores high on FLN. Oftentimes, FLN is accompanied by twin policy reforms that increase the role of the private sector, e.g., by pushing back on the Right to Education Act and its mandatory infrastructure norms. This often comes framed as “outcome orientation” or “innovation”. Essentially, education becomes commodified by codifying its quality through standardised assessments with a baked-in FLN-focus – a very narrow definition of quality. But a definition that is in the very interest of privatisation advocates who push for voucher systems and deregulated private education markets cheered by their philanthropic support network. Here, again, a striking contrast becomes evident between what the schools of the poor ought to focus on and where the advocates for FLN send their own children (i.e., private schools with lavish infrastructure and a holistic understanding of education).

What is the alternative?

If the current understanding and policy framing of FLN is problematic, then what is a viable alternative? How can India’s schools be improved on scale so that every child receives an education that ensures that they can achieve their full capabilities? There are no silver bullets or shortcuts. Ultimately, India needs a professional teacher cadre, investments in its teacher training institutes at the state, district, block, and cluster level, and investments in its government schools. All of this is currently neglected. District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs) often have high vacancies, insufficient funds, and severe constraints impeding them from acting responsive to local needs. How a faculty of five people shall organise in-service training for thousands of teachers remains an unanswered question. While policymakers have attempted to sideline these perceived bottlenecks through distance courses and online platforms, evaluations of such programs have revealed that they are hardly effective. There is no shortcut to investing in a strong academic support system that is equipped to train the teachers we need for 21st century schools. Neither ICT nor PPPs are feasible alternatives. This core function of an education system requires a strong public sector, sufficient human resources, and a proper infrastructure. Gearing an entire education towards mastering FLN while ignoring this crucial academic infrastructure will backfire. Instead of jumping on the FLN bandwagon, policymakers should consider increasing budgetary allocations for teacher training institutions and reformulate their mission and mandate to ensure increased discretion and an empowered faculty.

Conclusion

Education systems in many countries, in an attempt to boost learning quality, have moved away from teaching reading and mathematics in incremental, skill-based ways. Culturally responsive teaching, that strives to make learning relevant to the lived realities of children, and critical mathematics education, which teaches math as a tool to critically read the world, are among several approaches widely sought after by schools worldwide. These approaches include mastering basic reading and math skills as part of a richer, contextual learning – rather than a prerequisite, as envisioned under FLN. Achieving such high-quality learning experiences in classrooms requires equally high-quality teacher preparation and in-service training programs – something India lacks severely as of now. We are not claiming that reading proficiency or arithmetic skills are unimportant; they are certainly essential components of a quality education experience. However, formulating learning as only the mastery of piecemeal reading and arithmetic skills entails a simultaneous overlooking of and lack of imagination around other holistic components of learning. Additionally, it further restricts teacher discretion and innovative teaching, as they are primarily expected to show only student mastery on sequential, pre-determined skills. Centering the education of children in rural and marginalized communities narrowly around mastery of FLN reinforces outdated, rote, and decontextualized forms of learning. It also presents serious risks of replicating age-old inequities for these children, without any forays towards contemporary educational goals such as critical thinking, curiosity, or empowerment. We, however, need to move forwards, not backwards, if we want to achieve quality education for all children.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

This article was first published on: Hindustan Times

Featured image credit: World Bank via Flickr

Nice articulated and Well written, Martin

NGO-isation if anything is bad, more so in education. Modi government is not expected to understand the importance of good education. Everyone knows why.

Good job. Keep up the pressure.