ID alumna Shreya Gulati and co-author Anand Babu consider China’s continued rise in the context of the country’s role as a major development finance creditor, probing some of the accusations of a ‘debt trap’ strategy that have been levelled against the Asian superpower.

“Let China sleep, for when she wakes, she will shake the world”; whether these words belong to the legendary French leader Napoleon Bonaparte or not, it seems to be prophetic from the vantage point of the 21st century. It was Deng Xiaoping who reintroduced the deep-rooted Confucian concept of ‘xiaokang’ (a moderately prosperous society in all respects) to the Chinese political and economic discourse in the late 1970s. The concept of a ‘xiaokang’ society was based on the grand design of the ‘four modernisations, which emphasised transforming China into a strong socialist country with modern industry, agriculture, transport industry and defence. These efforts have been successful, the sleeping dragon has finally awoken, and China’s strength continues to grow.

Debt trap diplomacy?

Along with the stupendous growth of its real economy, China emerged as one of the global leaders in international development finance and currently stands as the largest official creditor in the world. In the past couple of decades, the Chinese government and its state-owned Banks have extended their presence and financial support on a global scale. In 2013, the Xi Jinping administration initiated One Belt One Road (OBOR) programme — now Belt and Road Initiative— which is a massive assortment of investment projects spanning across different continents. However, the U.S.-led western block claims that the BRI is in fact a geopolitical strategy to pave the way for a new, Sinocentric world order.

In 2018, the U.S Vice-President Mike Pence alleged that the Asian giant is ingeniously playing ‘debt trap diplomacy’ to ensnare smaller countries with onerous levels of unproductive debt. To put it more specifically, China inveigles underdeveloped and developing economies to borrow and build economically non-viable infrastructure projects and eventually take control of these strategic assets from the debtor countries when they run into financial problems.

The Sri-Lankan fiasco: Is China responsible?

Two examples often cited to support this theory are the Chinese funded Hambantota Harbour and Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport (MRIA) projects in Sri Lanka, However, a closer look would reveal that it was the callous domestic political decisions that pushed the island nation into severe balance of payment (BOP) crises and exponential rise in external debt, not the Chinese alliance per se.

The original idea of Hambantota port was not proposed by the Chinese; it was first mooted by a local parliamentarian D.A. Rajapaksa in the 1970s. Later in 2006, equipped with a favourable feasibility study conducted by the Danish firm Rambøll, the Sri Lankan government had initially approached India and the United States for funding. However, the lukewarm response from both countries opened doors for the Chinese construction firm ‘China Harbour group’. With funding from the China Exim Bank, the Chinese company won the contract.

The need for a second international airport in Sri Lanka was long overdue. The Mahinda Rajapaksa government chose Mattala, a tiny rural town situated 18 kilometres away from Hambantota town and 250 kilometres from Colombo for the new international airport. The $ 209 million Chinese funded airport was one of the main pillars of President Rajapaksa’s ambitious plan of transforming his rural hometown and political constituency into a metropolis like Colombo. However, the spatial disadvantage of the airport backfired. According to the government data in 2014, the average number of passengers travelled per flight from this international airport was incredibly low: seven to be specific! Interestingly, back in 2006, U.S. diplomats had observed the phenomenon of political greed overriding the welfare aspects in Sri Lanka.

The African lesson

The Chinese belt and road ‘invasion’ in the African continent is another stereotype that has to be debunked. There is absolutely no doubt that in the past two decades, China has built large infrastructure projects in as many as sixteen African countries by creating twenty five economic and trade cooperation zones. The Asian Superpower has continued to invest heavily across the continent throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.

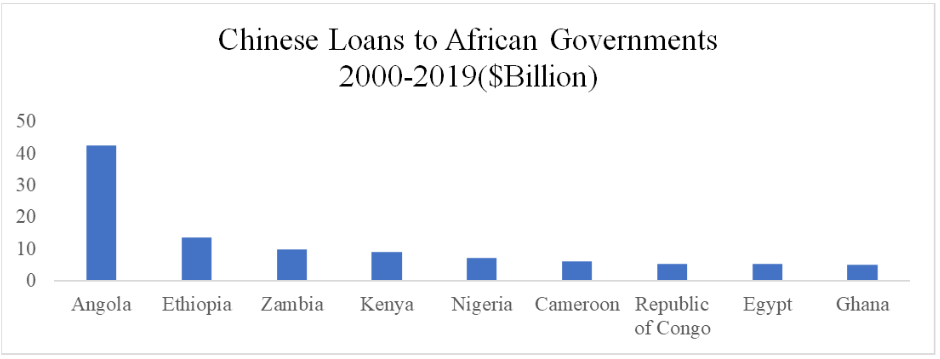

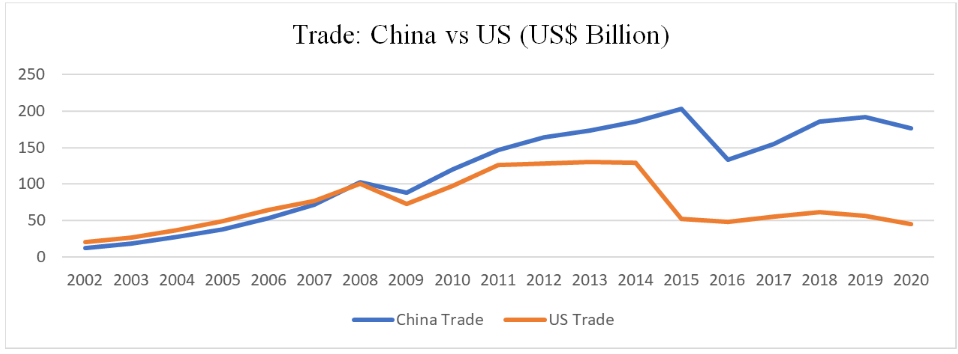

The data clearly indicates that Africa is not currently facing a massive Chinese debt trap, (Figure 1.1). The top ten African countries’ total debt to China stands at 109.2 billion U.S. Dollars as of now. Moreover, the problem will be diluted further, if Angola can be taken as an outlier, as it contributes nearly forty per cent of the total debt. As a matter of fact, African countries are eager to establish their identity and are not looking for charity anymore. Rather, it seems they are happier to be treated as trade partners. While China has recognised this paradigm shift and acted swiftly, the United States and its allies failed to re-align their Africa policy. This is quite evident from several economic indicators pertaining to the African continent that include export/import, trade and foreign direct investment (Figure 1.2).

A Sinocentric world order in the offing?

Classifying Chinese investments in developing countries as a strategically designed neo-colonialist policy tool would be an exaggeration. However, even an unbiased observer might not give the Asian juggernaut a clean sheet. When countries receive Chinese investments, they are expected to side with China at various international forums and abstain from condemning China on geo-political issues ranging from Taiwan to the state sponsored atrocities in Uyghur. Also, there are serious allegations suggesting, Chinese firms using unfair means to win contracts in foreign countries.

In his book ‘The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order’ the former Brookings Fellow Rush Doshi explains China’s three strategies to displace U.S. hegemony. The first strategy of displacement (1989–2008) was to quietly diffuse the American influence over China. The second strategy of displacement (2008–2016) was to build the foundation for the Chinese hegemony in Asia which was launched after the ‘global financial crisis’. The launch of the third strategy of displacement coincides with Brexit, the Trump era and the west’s poor Covid-19 management. In this phase China aims at blunting and displacing the United States as the global leader.

The increasing political clout of China in the past two decades is an undeniable fact. Beijing’s aspiration to become a global superpower is stronger and more vocal now than ever before. The political ambitions of a modernised military power backed by a 19 trillion USD economy will certainly cause tremors in the global order. Also, its near monopoly in rare earth metals gives China an upper hand over the G7in the race to dominance in the renewable energy market.

Countries that are sceptical about the rise of China as a global superpower must realise that rising powers are most effectively contained by forming countervailing coalitions. With the backdrop of the ongoing economic and political turbulences on a global scale, and especially in the South-Asian region, it is the right time for India and G7 member countries to build and strengthen strategic political and economic alliances to restore and retain the regional and global balance of power.

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Chinese president Xi Jinping with Angolan president José Eduardo dos Santos in 2015 via China Daily Asia.

Andy Vermaut here. Please contact me by Whatsapp on +32499357495 I am organizing the 8th of september 2022 an event in Brussels regarding the China Debt Trap.