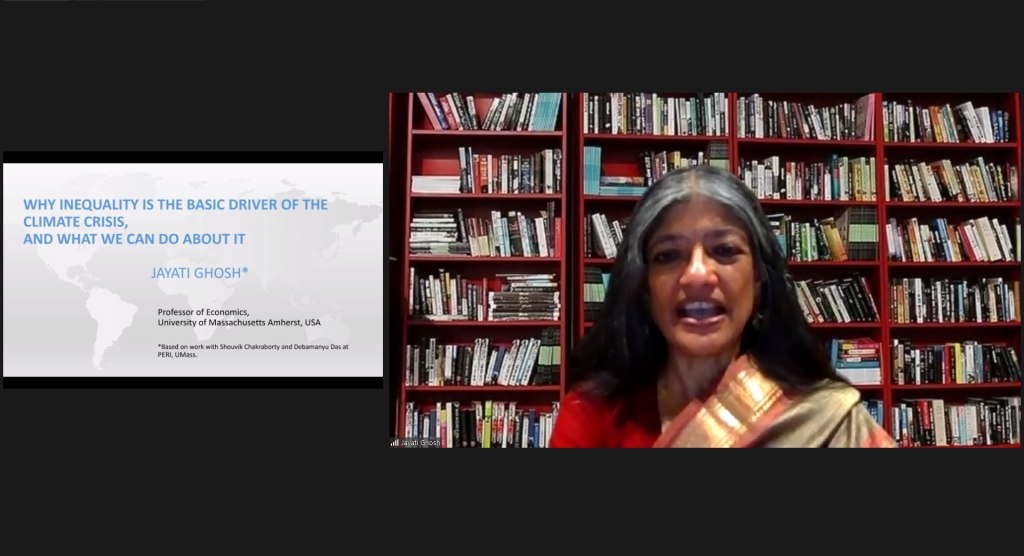

On Friday 18 November, Jayati Ghosh gave an online lecture at the LSE as part of the Cutting-Edge Issues in Development lecture series on “Why Inequality Is The Basic Driver Of The Climate Crisis, And What We Can Do About It”, with Professor Kathryn Hochstetler as discussant.

Jayati Ghosh is Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, USA. She has authored and/or edited 20 books, including a co-authored book, Earth For All: A survival guide for humanity published in September 2022. Read what Eunice Asantewaa Hansen-Sackey, Sharda Dean and Maria Zaccaria took away from the lecture below. You can watch the lecture back on YouTube or listen to it as a podcast.

The just-ended 27th Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC (COP27) in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt has reignited the urgency of climate change mitigation and adaptation and the importance of reducing carbon emissions. In the latest Cutting-Edge Lecture series, Professor Jayati Ghosh dissected the issue of inequality as the basic driver of the climate crisis and proposed practical solutions to reducing carbon emissions to slow down the adverse effects of climate change.

She started off by expressing the failure on the part of the COP27 sessions to address the issues of inequality in the global climate crisis and proposed that the reports released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) be taken seriously especially now that climate change is no longer in the future but is already here and affecting our eco-system. In her analysis, each report reveals the widespread damage, much of which is irreversible. For instance, many species are now extinct, sea levels keep rising in parts of the Caribbean and all these effects have socio-economic and physical consequences on livelihoods in developing countries that are extremely vulnerable.

On climate adaptation, Professor Ghosh argued that there are large gaps for developing countries due to access to resources; however, she raised concern about ‘mal-adaptation’ as described by the IPCC where worsening climate conditions result in the release of more emissions. An example is warmer temperatures leading to the purchase and use of more air conditioners which is bad for the environment.

Speaking on inequality, she questioned the current system used to measure carbon emissions per country because of the failure to account for historical carbon data and carbon debt. Another problem she cited is that carbon emissions are measured according to production and not consumption. Many countries in the global north import rather than produce carbon, leaving countries like China and India with high emissions for producing goods that will be exported. She further argued highlighted the injustice of the current allocation of carbon responsibility by stating that between 1850 and 2011, 80% of the emissions came from the richest countries and more than half of these emissions happened in the last 30 years.

She followed this by proposing solutions and alternatives to measuring carbon, recognizing that the current system doesn’t take cross-border trade into account. She suggested that for extractive-based emissions, for instance, the life cycle of fossil fuels should be assessed, and responsibility allocated to all parties involved. Another approach can be the introduction of value-added emission which allocates emissions to countries according to the share of value added from the lifecycle of the product in each step of the value chain and the carbon emissions in that step. In her view, the easiest approach to measuring is looking at emissions based on domestic consumption of specific products. All the life-cycle emissions of those products can be calculated and then allocated to the final consumer. In her opinion, this is a more just way of allocating responsibility to reduce emissions.

Currently, China is the largest emitter of carbon and has more than tripled emissions in the last two decades. However, in questioning the inequality in the system of measurement, Professor Ghosh identified that countries like the US, UK, France, and Germany are net exporters of carbon emissions because China and other countries produce the emissions on their behalf. Therefore, it is more accurate to analyse the emissions of consumption, which has the US leading with 18.1 MT IN 2015. The significance of trade and the ability to export more carbon-emitting products must be considered.

She concluded by referring to a report by the World Inequality Lab which analysed data on emissions within countries and regions. She highlighted that the inequality of carbon emissions among the categories of income is crucial in measuring carbon emissions within countries. For instance, the per capita emissions of the bottom half of the population of North America account for less carbon than the richest category of all developing countries. Also, the richest in South and Southeast Asia are well over double the bottom half of the population of Europe. She added that although the emissions of the bottom half of the population have been declining over the past decade in all regions, the top 10% of the world are the worst emitters. She closed by reiterating that reduction of energy use or switching from fossil fuels like petroleum and natural gas to nuclear, solar and other forms of renewable energy is a viable solution. Professor Ghosh commended many countries for attempting to switch to cleaner energy and reducing their share of carbon-emitting energy sources.

— Eunice Asantewaa Hansen-Sackey

_________________________________________________

It was a rare treat to listen to Professor Jayati Ghosh who spoke with characteristic precision and clarity. With COP27 ending in Egypt, it was a well-timed event, our heads already full of the recent news coverage of the negotiations on ‘Loss and Damage’. As a somewhat mature MSc student, I have been following the debates on the environment since the 1990s but there was plenty here to be inspired by. Ghosh reminded us that half the carbon emissions humanity has been responsible for have occurred in the last 30 years when we were already very aware of the harm that we were doing to the planet. Progress has, in part, been slow due to wrangling over who is most to blame and who has most to pay. Professor Ghosh’s perspective that carbon emissions should be calculated on where goods are consumed, not on where they are produced, was a simple and effective way of removing the effects of trade on carbon emission accounting. By this metric, the US is way ahead of the emissions league table with 18.1 metric tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2019 compared to India with just 1.5, and China with 5.7 metric tonnes. She also showed us the exact effects of trade on different countries’ emissions. Countries such as the US, Japan, UK, France and Italy are all net exporters of emissions – importing many manufactured goods produced abroad, but leaving the emissions those goods produced to cloud the air of cities in China and India.

The analysis Professor Ghosh presented apportioning emissions by income group within and across countries was fascinating. Unsurprisingly the top 10% of the world’s earners are by far the worst emitters, regardless of where they live and, what is more, despite their Tesla purchases, their emissions have accelerated in the past ten years. By contrast the bottom half of the population have seen their emissions falling. This analysis can help to make policy more effective. If it’s the rich who are doing the emitting, then a carbon tax, which tends to hit the poor hardest, would be an ineffective (and unfair) policy option. Of course, much needs to be done, but Ghosh’s parting thoughts were optimistic and her proposed solutions seemed eminently sensible. Why come up with market-based financial solutions when the countries suffering most, like Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands and the Maldives do not have financial markets and will remain unaffected by such measures? With 1.5% of global GDP all that is required, and much more than that spent during COVID, what are we waiting for?

— Sharda Dean

_________________________________________________

In Friday 18 November’s Cutting Edges lecture, Professor Jayati Ghosh proposed to answer two important questions on climate change: why is inequality the basic driver of the climate crisis, and what can we do about it? The author of Earth for All exposed in a clear and enlightening way the key factors that drive us toward an inaccurate interpretation of what is causing the climate crisis.

As the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) are telling us in an alarming way, the climate crisis is no longer a problem of the future. Therefore, we must act now, and we must do it in the most effective way, including being open to important changes in the way we are dealing with the climate crisis. For example, switching from a production-based method of determining carbon emissions to a consumption-based one gives us a much more accurate vision of which countries are the largest emitters. By doing so, we can observe that the richest countries ie the countries of the North, are the ones who are really getting the benefits from the carbon emissions on behalf of the poorest countries. Moreover, by taking into account the carbon debt we realize that today’s developed countries are responsible for almost 80% of carbon emissions between 1850 and 2011.

One of the solutions proposed by Professor Ghosh is to use Market Exchange Rates and not Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) exchange to determine GDP and thus, climate obligations. She also focuses greatly on Global Public Investment as a basis of climate finance and on starting to approach the climate crisis as a global issue and no longer at a national level.

What I found the most enlightening in Professor Ghosh’s lecture, is her observation that there is massive variation of the per capita emissions within countries. The bottom half of the population of North America is emitting less carbon than the richest categories of all developing countries. As reported by Oxfam in 2020, the richest 10% of the world added 52% of carbon emissions between 1990 and 2015, and the richest 1% added 15% of emissions, ie, more than all the citizens of the EU and more than double the poorest half of humanity (7%).

She proposes different solutions to all the incongruities of the current system and she concludes by explaining how a great focus should be put on the carbon emissions of the wealthy, by regulating their (completely insane) activities. Some solutions would be to tax them, ban luxury carbon spending such as SUVs or private jets, or even ban private rides to the moon.

A future in which taking a 15-minute flight on a private jet is acknowledged as an irresponsible act and is thus banned is one I wish for upcoming generations. A world in which we genuinely thank Kim Kardashian for eating plant-based tacos, but in which we also claim a bigger environmental engagement from her and the rest of the super-rich would be a more rational and fair one.

— Maria Zaccaria

The next guest lecture in the Cutting-Edge Issues in Development series will be an online panel event on Platforms for deliberation or disinformation? Social media and development with Nanjala Nyabola, Idress Ahmad, Amil Khan and Dr Kecheng Fang on Friday 2 December. Register to attend via Zoom.

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main Image: A private jet aircraft floats along the wall of Chennai International airport after floods sweep through southern India following record rainfalls, December 3, 2015. Credit: Alamy via climatevisuals.org.

Hey Eunice, Sharda, and Maria! I love this article. You have shown great insight into the various experiences each of you has had in your respective fields and how that can be applied to development management.

I appreciate how you focus on the importance of having a holistic view of development and stress that it is not just about economics but also social and environmental considerations.

I believe it is crucial for practitioners in any field related to development to understand the context in which they are working.

It is essential to think beyond the economic indicators such as GDP growth, inflation rate, etc., and how policies affect communities regarding access to essential services and opportunities.

This post has highlighted key issues, such as the need to consider gender, culture, and environmental sustainability when planning development.

This article demonstrates the importance of education in ensuring that those involved in development management know their responsibilities.

It is also essential to have an open mind and be willing to engage with different stakeholders, especially from local communities, to ensure that policies are inclusive and responsive to people’s needs.

I think this post has been a great source of inspiration for anyone interested in working in the field of development.

Thanks, Eunice, Sharda, and Maria, for such an informative article!