Dr Elliott Green tells us about his new book Industrialization and Assimilation: understanding ethnic change in the modern world, which explains how and why ethnicity changes across time, showing that, by altering the basis of economic production from land to labour and removing people from the ‘idiocy of rural life’, industrialization makes societies more ethnically homogenous.

Despite high expectations as countries across Africa became independent of colonial rule in the 1950s and 1960s, the continent soon began to experience widespread problems with state collapse, conflict and underdevelopment in the last three decades of the 20th century. Social scientists searched for explanations as to why African states were underperforming: particularly influential in this regard was a seminal article by William Easterly and Ross Levine that argued that “Africa’s Growth Tragedy” was a consequence of its high level of ethnic fractionalization. This paper – which today remains by far the most-cited among all of Easterly’s work – has led to a cottage-industry of examining the effects of ethnic fractionalization on various outcomes across the world, including economic growth and unemployment, civil wars and public goods provision, among other phenomena. While much of this literature has been useful in understanding underdevelopment in the developing world and in Africa in particular, this body of scholarship has treated ethnicity as fixed and unchanging, assuming, to take one example, “that the extent to which countries are fractionalized along ethnolinguistic lines is exogenous and unrelated to economic variables.”

The goal of my book is to show that ethnicity is not in any way exogenous to changes in society, and, more specifically, that industrialization causes assimilation. It is theoretically built upon an older set of social science scholarship that emphasized the role industrialization and capitalism can play in generating social change, whether in terms of class formation for Karl Marx or the creation of national identities for Ernest Gellner. In both cases social identities can seen as having instrumentalist value, whereby individuals choose their identities by the benefits they bring. The process of industrialization generates a shift from economies based on the control of rural agricultural land to ones based on labour in urban areas. This shift thus generates incentives for individuals to shift their primary ethnic identification from more narrow rural ethnic identities towards broader urban ethnic identities as a means to make ends meet in modern industrial society, leading societies to become more homogenous as they industrialize.

I use both quantitative and qualitative evidence to test my argument. In the former case I take two different datasets that measures levels of ethnic fractionalization by country over time – the first a set of indices compiled by Soviet ethnographers in 1961 and 1985 and the second a new, original dataset that I compiled based on country censuses across the world dating back to 1960 – and show that various measures of industrialization are negatively correlated with a measure of ethnic fractionalization. Moreover, I show that several measures of state capacity and education are not correlated with declining levels of ethnic fractionalization, which throw into question theories of nation formation and assimilation that focus on the role of government policies.

The rest of the book focusses on a variety of case studies. I start with mid-20th century Turkey, due in part to the existence of high-quality census data that allows me to show a relationship between industrialization (as measured by urbanization) and assimilation over time, as well as the fact that this period saw significant amounts of both industrialization and social change. The Turkish example again demonstrates the limits of a state-centred approach to nation-building, inasmuch as the part of Turkey that saw the most violent state presence, namely Kurdistan, was also the least industrialized and thus saw the least amount of assimilation during this period.

I then move on to three cases studies from Africa, namely Somalia, Uganda and Botswana. The first two cases are examples of African states that have failed to industrialize and thus continue to see high levels of ethnic fractionalization. While Somalia saw extensive efforts at nation-building under President Siad Barre, its lack of industrial growth failed to generate cross-clan national identification, leading the country to break apart on clan lines in the 1980s. In Uganda the continued relative high value of agriculture has led to continuing ethnic claims over land and even attempts to get the government to recognize new ethnic groups in the constitution. Botswana provides a strong contrast to both Somalia and Uganda, as a country which saw both the highest economic growth per capita and rate of urbanization in the world over a matter of decades. The success of its diamond industry – which is featured in the cover image of my book – has led to a sharp decline in the relative value of agriculture in the economy and led Botswanans to increasingly identify as Botswanan rather than according to individual tribes or merafe.

The book concludes with two case studies of indigenous ethnic minorities from the developed world, namely Native Americans in the US and the Māori in New Zealand. These cases are important for my argument because they are both rare instances of de-industrialization as regards the relative value of rural land and allow me to test whether my theory works in reverse. More specifically, in both cases industrialization in the mid-20th century led Native Americans and Māori to migrate to cities and form broader pan-tribal identities. However, legal rulings in both states in the late 20th century granted economic benefits to individual tribes according to their rural land holdings, namely casino rights in the US and fishery rights in New Zealand. These rulings generated a reversal of assimilation in both cases, such that tribal identities have become revitalized and caused a fragmentation of pan-tribal movements.

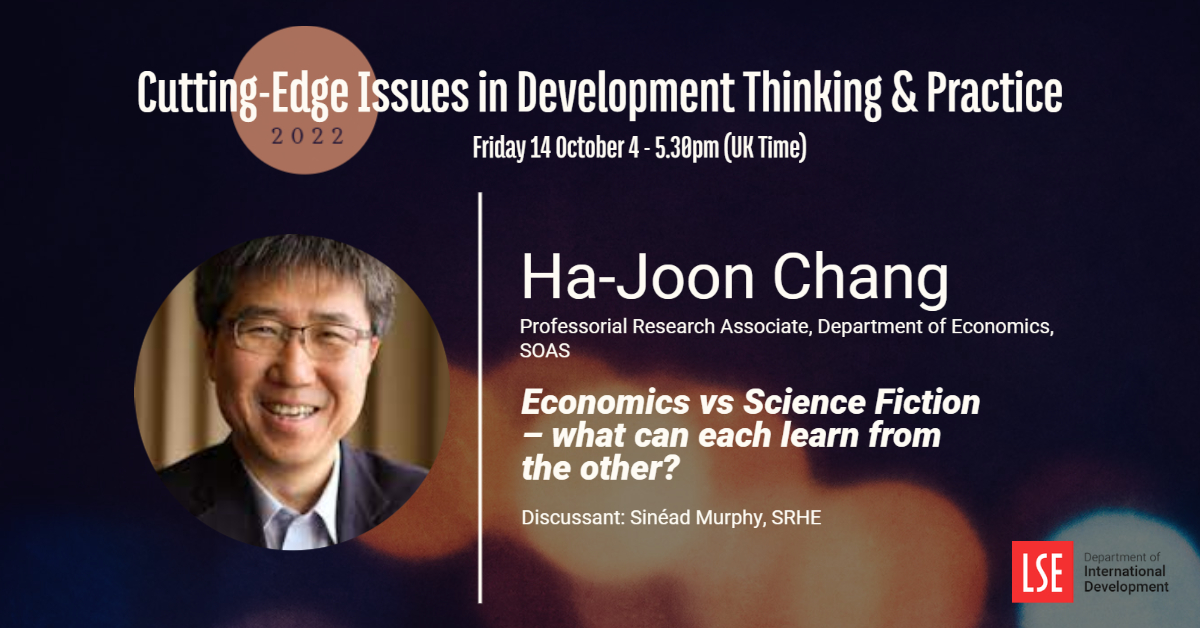

My book thus uses multiple forms of evidence and case studies to show that industrialization causes assimilation in the modern world. There are several ‘take away’ lessons from the book. One lesson is a recognition that ethnicity is changeable and not fixed, and that it is normal that individuals might want to change their ethnic identities given changing circumstances. A second lesson is that governments have less power in their ability to direct and shape identities than is broadly assumed: the book demonstrates both cases of attempted but failed assimilation (such as in Turkey and Somalia) as well as unanticipated and unplanned identity change as a result of state policies (as with the Native Americans and Māori). Finally, the book suggests that the role of industrialization in shaping societies is not just limited to its large economic effects but also includes its effects on ethnic identification, and that ongoing attempts to underplay industrialization’s role within development studies is, to put it in Ha-Joon Chang’s words, ‘development without development.’

Join us for the public book launch of Elliott Green’s book, Industrialization and Assimilation: Understanding Ethnic Change in the Modern World, on Thursday 9 March from 6pm in MAR.2.04. More information here.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Remy Gieling via Unsplash