Zachary Wahab Cheek argues for market-based trade facilitation as a means of furthering development goals including poverty alleviation and environmental protection.

The significance of trade for development has long been debated by scholars and policymakers. While the exchange of goods and services is a phenomenon almost as old as mankind itself, the impact of trade within contemporary development policy is by no means a topic of wide consensus.

While one blog post will surely not resolve such a passionate policy discussion, I write here to touch on current perspectives in trade and development policies; and more specifically, markets. Historically, trade has been liberalised through the removal of barriers such as quotas and tariffs. In other words, it has focused on “market access.” The advent of the World Trade Organization (WTO) has done much in this regard to remove top-down barriers to the exchange of goods and services. But market access comprises a much smaller share of initiatives in current trade policy, leading one to question what trade really means for development today.

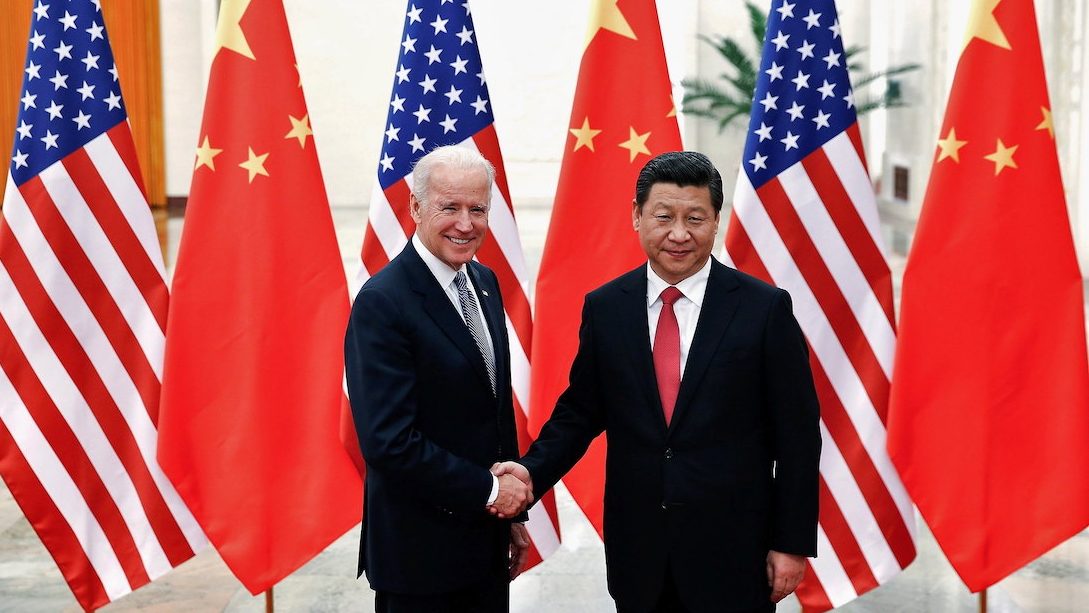

The US used to be one of the greatest supporters of the global trading system. While the world’s largest economy for decades happily negotiated free trade agreements with lower-income nations such as Jordan and Colombia, US trade policy today is much less keen and much more ambiguous. Former US President Donald Trump, for example, pulled America out of an Indo-Pacific free trade deal negotiated under President Barack Obama, thereby denying further trade with Southern nations such as Vietnam and Malaysia. In a rare moment of agreement between the two presidents, the government of President Joe Biden similarly didn’t seem to care for market-oriented trade with the developing world, instead proposing a trade deal with the Indo-Pacific which favours issues like labour and the environment instead of market access. The response of Indo-Pacific nations have been expectedly unenthusiastic. It was also hoped this would undermine Chinese economic influence in the region, but its success here is debateable. To the US government, it appears, trade then means a way in which to pursue social agendas (such as labour reform and climate protection, as mentioned) and counter China, but little else.

The rest of the North has been similarly anti-market with regards to the South. Take for example the Doha Development Round, a series of WTO-facilitated negotiations intended to substantially lower global trade barriers. The Doha Round, convened in Qatar in November 2001, largely failed because of Western countries’ opposition to ending their own agricultural subsidies. These policies, such as the European Union’s Common Agricultural Program, have significantly disadvantaged the developing world, and countries like India justifiably wanted concessions in this area. But the negotiators were fervently opposed to reforming these restrictions on transnational commerce, despite going to Doha for the express purpose of addressing standing obstacles to trade.

Talks fell through because of this deadlock, and most of the world today can confidently declare Doha dead. When WTO director-general Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala visited the LSE this term, however, she discussed continued optimism in Doha (which officially has not concluded despite an evidenced lack of confidence in it). Perhaps then, against all odds, the best of Doha is yet to come. And perhaps Western countries are realising their mistakes: only recently have nations like the UK expressed more eagerness to trade with lower-income nations such as India, or that same Indo-Pacific region which two successive American presidents (of different parties) have denied.

The Global South seems to agree, meanwhile, that trade still means greater market access, and thereby development. Take for example the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), a continent-wide free trade area established in 2018. Sources project that by lowering tariffs on nearly 90 percent of goods traded, AfCFTA will produce a range of positive results for trade, agriculture, and economic growth on the continent. Notably, it will also lift 100 million Africans out of poverty and immensely improve African air quality; two areas (labour and climate) the Biden Administration claims it better pursues in neglecting the market aspect of trade facilitation.

So, trade can mean environmental protection and poverty alleviation? If conducted in market-based ways, it is likely so. Major institutions such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and WTO have long argued that trade facilitation is indeed part of the solution to development agendas addressing poverty. The same can be said for environmental protection; trade is not simply a question of economics, but also one of regulation and the law. Making nations’ environmental policies more compatible via regional and bilateral trade agreements, it has been argued, can thereby produce great benefits for the environment when otherwise there would be none.

The facts then seem to suggest that trade can in the long term mean better development for everyone, if policymakers simply prioritise freer markets and freer trade. As AfCFTA demonstrates, pressing issues in the development sphere today such as environmental damage and poverty can be significantly addressed through barrier-reducing changes to standing trade regimes. These issues have evidently found their best success when this is done. Furthermore, the goals of greater equality, better living standards, and environmental protection espoused by those who oppose market-based trade have in recent times been best pursued by the same economic globalisation they denounce.

Market access has a substantiable role to play in the creation of global trade agreements today, just as it has for many years. The deliberate curtailing of markets has irritated would-be trade partners across the developing world, while embracing them has empirically seemed to benefit a host of development-related causes. If the world is to achieve better North-South economic relations, freer trade must play a leading role. To that end, policymakers in developed nations (such as those in the Biden Administration or European Union) should realise that their goals are best achieved through, rather than without, market promotion.

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image Credit: A lock on the Panama Canal via pxfuel.

Well written