Guest blogger and Visiting Fellow in the Department of Media and Communication at LSE, Dr Grace Yuehan Wang explores the history of BRICS and the influence of China in the ‘network’.

2023 BRICS (i.e., Brazil, China, India, South Africa and Russia) Summit to be held in Johannesburg, South Africa is approaching. Different from the view that BRICS is an alternative to the G7, I argue that BRICS is not a bloc but a network that shares similar attributes – developing countries in the Global South that wish to advance their economies. A ‘network,’ refers to a group of actors (in network language, actor is called node) that have an interdependent relationship. These nodes might have a direct relationship or there may be no direct link between them, depending on their strength. Each BRICS member is a node in the BRICS network, but some members maintain or are trying to seek additional networks outside BRICS.

BRICS is not an alternative to the G7 because of its members’ political and ideological differences. Its possible expansion demonstrates a shared desire among developing countries for unification and for their voices to be heard and taken seriously on the global stage. But, the BRICS multilateral governance framework and the organization’s sustainable development still has a long way to go, particularly during a period when BRICS is adding aspects, for instance, political governance, to its existing network, raising potential conflicts of interest in relation to some members’ other networks.

The BRICS Emerged Out of An Investment Dream

BRICS’s initial formation was built on a Western capital investment dream. The then-chief economist of Goldman Sachs, Jim O’Neil, coined the acronym in his report, “Build Better Global Economic BRICS,” in which he voiced economic optimism about the future growth of those nations. His prediction came as the United States’ post-Cold War economic expansion was ending, and the US economy entered a recession in March 2001 following a ten-year growth period. The economic slowdown likely encouraged the exploration of new markets and emerging economies.

From 2001 onward, only the Chinese economy has fully achieved its potential, with its GDP exceeding $14 trillion as of 2019. China’s GDP growth contributed to a significant portion of BRICS’s share of global GDP from 18% in 2010 to 26% in 2021, with over 70% of BRICS GDP coming from China.

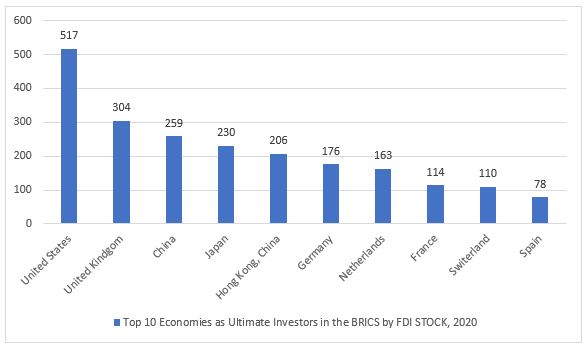

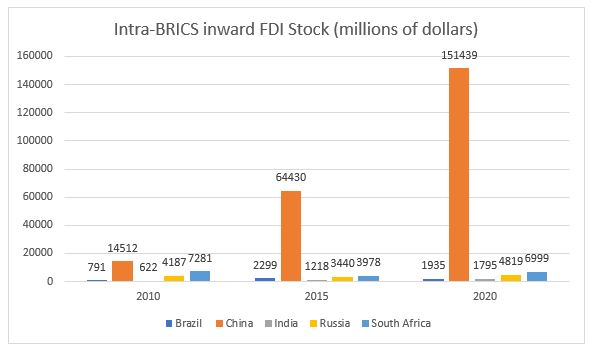

According to UNCTAD data, the top 10 investor economies in the BRICS countries remained roughly the same over the past years, measured by FDI stock. As shown in Figure 1, the United States was the largest investor in BRICS and the United Kingdom ranked No. 2, while China ranked the third with an increasing participation within BRICS. Among the top 10 investor economies, five of them are G7 members. Despite different economic development trajectories and prospects, BRICS strengthened its organizational core through the advancement of their economies by establishing the BRICS Development Bank which was founded in 2014 during the sixth annual summit in Brazil, later renamed New Development Bank headquartered in Shanghai. Figure 2 demonstrates investment among BRICS countries, of which inward FDI stock increased from $27 billion in 2010 to $167 billion in 2020. China is the largest investor and recipient of investment among BRICS countries, whose inward FDI stock accounted for about 90% of the total BRICS inward FDI stocks in 2020. Those figures indicate that BRICS global influence as a group of emerging markets and economies largely seems to be supported by only one country, China. It is surely inappropriate to call a country like South Africa an emerging global power when the country is failing to maintain its own electrical power. So, the question is: Is BRICS an alternative to G7? Or could it be?

An Alternative to the G7?

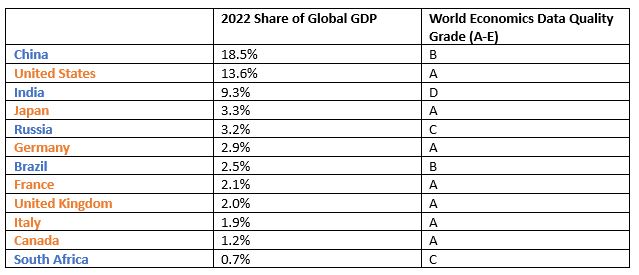

The founding principle of the G7 differs from the origin of BRIC(S). In 1975, the United States, France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and West Germany formed the group of six noncommunist powers to focus on economic issues, security concerns, and world politics. Canada joined in 1976. The G7 as a network enjoys the following commonalities: 1) Western democracies 2) industrialized countries 3) non-communist powers. From 2012 to 2022, the G7 accounted for 27% of global GDP and 15% of global GDP growth. As Figure 3 indicates, China tops the 2022 share of global GDP with a World Economics data quality ranking of B, the best-performing country in BRICS in terms of quantity and economic data quality. India has a 9.3% share of global GDP, but its data quality is a D. Russia shares a similar percentage of Japan’s 2022 share of global GDP, but its economic data quality grades contrast dramatically. Therefore, despite the media hype around the BRICS’s global GDP share and the optimism towards BRICS’s future, the breakdown in Figure 3 reveals the actual economic strength of BRICS and G7. How the BRICS can develop in a healthy way when its collective economy is so heavily dependent on China remains a thorny question.

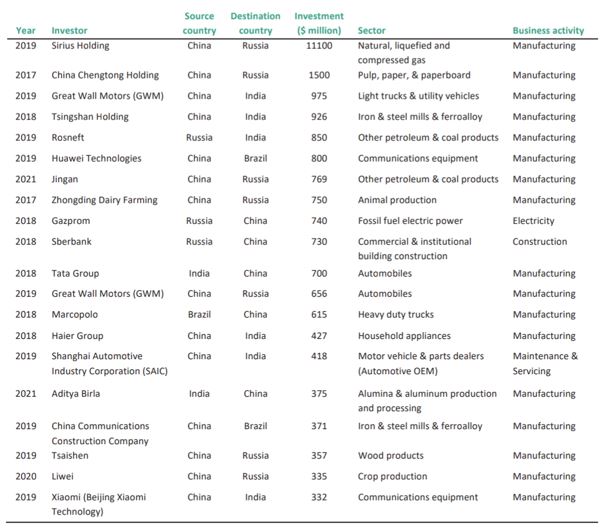

The rise of BRICS, both in terms of economic growth and share of global GDP, only indicates China’s economic rise in the last decade. The current BRICS dynamics seems to be that member states need China for survival while China wants them to thrive. As the political scientist Oliver Stuenkel argued, it brings countries such as South Africa, Russia and Brazil prestige, status and legitimacy to be a member of BRICS. It helps them gain easier access to Beijing and China’s financing, particularly in infrastructure, energy and manufacturing. Figure 4 shows the 20 largest intra-BRICS greenfield investments between 2017 and 2021 which demonstrates the inter-dependent relations between China and the rest of BRICS countries where China acts as a strategic investor. Take the manufacturing sector for instance. If China applies its own manufacturing as well as its technological upgrading and innovation lessons to those member states, it could foster a win-win BRICS manufacturing ecosystem. But that would depend on the host countries taking the initiative in participating in the intra-group manufacturing value chains by driving their domestic economic development. The key question, as I discussed in the podcast interview with the China – Global South Project, remains: Could local government officials in the host countries act like bureaucratic entrepreneurs by combining appropriate domestic economic policies with foreign investment? To answer that question, they need to look inward and ask tough institutional questions about their governance.

BRICS – Evolving Global Networks – A New Global Gold Rush or a Political Alliance?

China’s rising economy and its ambition to influence global governance shows the world that another way of governance is possible. My time as a researcher in South Africa showed me that China’s influence isn’t the sole reason for these countries’ challenge to the United States-led global order. It is also driven by their experience of external disrespect. For example, African countries’ struggle to access Covid-19 vaccines surely informed South African President Cyril Ramaphosa’s call for open access to markets, and his comment that “Africa should never be seen as a continent that needs generosity, we want to be treated as equals.” During Brazilian President Lula’s visit to China, his three questions at the New Development Bank were widely circulated: 1) why all countries are obliged to do their trade backed by the dollar? 2) why can’t we carry out trade backed by our currency? 3) why can’t it be RMB or Brazilian Real?

Those comments make it clear that BRICS is evolving from its conception as an investment-interested, financial-oriented network to a network with more attributes. The current dilemma of the BRICS network lies in the fact that it is trying to add more network attributes (including Global South political alliances) to an existing network formed according to a single network attribute (i.e., emerging economies in the global south). I wonder if countries who express their interest in joining BRICS understand which specific attribute of this BRICS network is attracting them. A new global gold rush or a political alliance? The nature of the links they want to forge will surely determine the success of their engagement, and the future shape of the network itself.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

This article has been republish with revisions from China – Global South Project.

Image: Xi Jinping before the start of the G20 summit in Hamburg, at an informal meeting of the heads of state and government of the BRICS countries. Image credit: www.kremlin.ru.