Patricia Owens presents an overview of the ‘Women International Thinkers’, curated by the Leverhulme Trust Research Project on Women and the History of International Thought (the WHIT Project) and discusses her anthology, Women’s International Thought: Towards a New Canon, which explores how women transformed the practice of international relations (IR).

The WHIT Project: Women International Thinkers

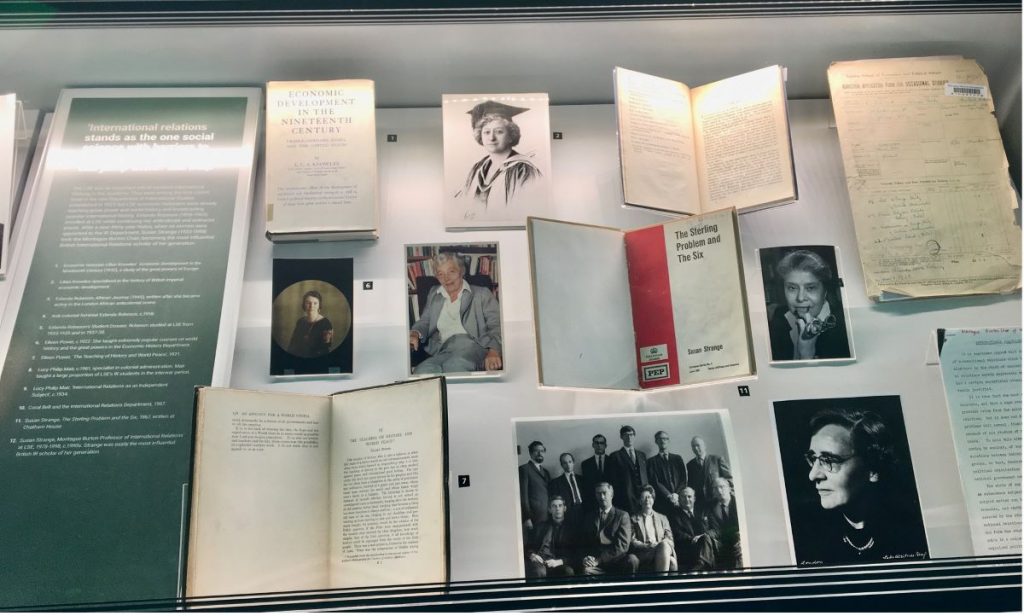

This Spring and Summer, the LSE Library is hosting a Public Exhibition, Women International Thinkers, curated by the Leverhulme Trust Research Project on Women and the History of International Thought (the WHIT Project). The opening of the Exhibition coincided with the publication the Project’s new anthology, Women’s International Thought: Towards a New Canon (Cambridge, 2022), which is the largest collection of international thought on how women transformed the practice of international relations (IR) currently in print.

Both the Exhibition and the anthology showcase early findings from the WHIT Project, which focuses on international thinkers working in Britain and the United States in the early to long mid-twentieth century. Unsurprisingly, several of these thinkers had LSE connections. The Exhibition includes a tabletop display centring just a few of these international thinkers who were either faculty or graduate students, both before and after the creation of a separate Department of International Relations at LSE, including Lilian Knowles, Eileen Power, Lucy Philip Mair, Eslanda Robeson, Coral Bell, and Susan Strange.

LSE exemplifies several of important themes in the history of women’s international thinking, including their presence and erasure in the academy, think tanks and policy making as sites of international thought, and the fluid intellectual and institutional boundaries of this intellectual field of international relations.

LSE as a site of women’s international thinking

LSE was an important site of women’s international thinking in the early to long mid-twentieth century and, more recently, an important source of support for the dissemination of work on this exciting new cross-disciplinary field of the history of women’s international thought. The anthology includes selections of work from at least sixteen figures with LSE connections. Some are quite well-known and were among the leading international thinkers of their generation, including Power, Robeson, and Strange, duly feature in the exhibition. Many others crossed over between academia, government service or think tanks, including Eleanor Lansing Dulles, Barbara Wootton, Louise Holborn, Corel Bell, Margaret Lambert, and Rachel Wall. Many also wrote on international relations from its early constituent disciplines, including colonial administrators Lucy Philip Mair and Margaret Read, economic historian, Lilian Knowles, and, of course, Economists, like Persia Campbell, Edith Penrose, Ursula Hicks, and Sudha Shenoy. Among others we couldn’t include are Vera Anstey, Hilda Lee, and Dorothy Pickles.

LSE exemplifies several of important themes in the history of women’s international thinking, including their presence and erasure in the academy, think tanks and policy making as sites of international thought, and the fluid intellectual and institutional boundaries of this intellectual field of international relations. From its founding, IR subjects were taught at LSE across the departments of history, law, politics and public administration by diplomatic and economic historians and lawyers. This matters not only because it points to the interdisciplinary nature of IR, but because not a single woman was hired in the International Studies department during Charles Manning’s tenure as Montague Burton Chair between 1930 and 1962. Dorothy Pickles was appointed to teach foreign policy two years after Manning retired in 1964. Charles Manning was not only a white supremacist supporter of Apartheid, he kept women off the IR faculty for thirty-two years, and married one of his own students, Marion Somerville Johnston.

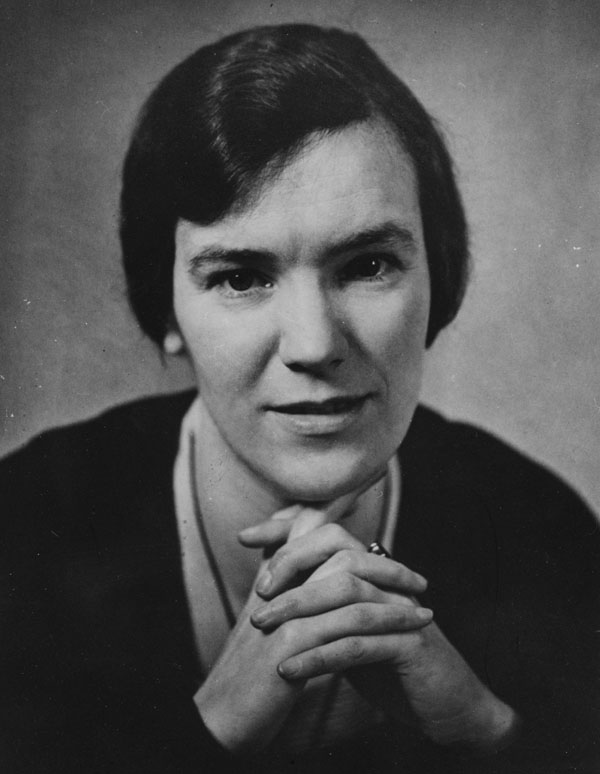

Professor Susan Strange, c1980s. IMAGELIBRARY/259. LSE

Women’s contribution to international studies

Manning’s reign was not only marred by racism and misogyny, but also, and necessarily so, intellectual impoverishment. Susan Strange, who held LSE’s Montague Burton Chair between 1978 and 1988, held Manning in contempt. As Brian Porter observed, she was rightly dismissive of the intellectual and institutional heritage that he left. But the justifiable attention to paid to Susan Strange’s intellectual and organisational dominance of British international studies in the 1970s and 1980s has obscured the breadth and depth of women’s international thinking in earlier periods.

During the 1920s and 1930s, LSE economic historian Eileen Power was increasingly well-known as a writer and thinker on world politics when ‘international relations’ was not yet fully formed as a separate university subject. According to her biographer historian Maxine Berg, LSE students “flocked to” Eileen Power’s lectures on the Great Powers and the Comparative World History of East and West. Power’s world history lectures were considerably more popular than Manning’s on the structure of international society. Power was well-known as a writer of popular international history, for consumption by workers and young people, an important and largely neglected part of IR’s own intellectual history.

In marked contrast to her male contemporaries’ failed attempt to develop a structural social theory of international relations, Eileen Power attempted to write ambitious internationalist world social and economic history. There are obvious limitations to Power’s work, including the Orientalism of her 1921 Kahn report, which reproduced a binary distinction between “east” and “west”, and thus traded in the civilisational tropes that she also set out to challenge. But she was no more marginal to the study of international relations in Britain in the 1920s and 1930s than numerous, and far less important male thinkers, whose work is repetitively analysed in international intellectual and disciplinary history. Yet, she completely missing in wider intellectual histories of British IR.

There should be no doubt that the erasure of figures like Power, working in Britain but also around the world, has impoverished our understandings of what international thinking was, is, and could be. It has shaped all international thought and the entire history of our field. And it is implicated in a range of academic practices today, from syllabus design and citation practices to the gendered, racial, and intellectual diversity and non-diversity of IR’s tenured faculty at its “elite” institutions, including Oxbridge and LSE.

The Public Exhibition is open until September 2, 2022. It is audio-described by the curators to enhance your visit or help you explore from home.

You can learn more about WHIT Project publications at their publications page here.

And you can follow them on social media here.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the LSE IR Department blog, nor LSE.

This article was originally published on the LSE History blog.